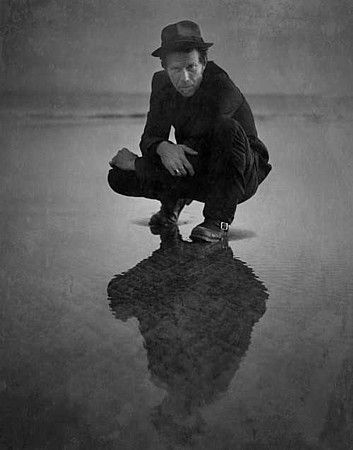

I remember watching Easy Rider as a kid. The desert. The dirt. The open nothing stretching forever. That soundtrack humming like a lazy rattlesnake in the heat. Something about it crawled into my blood and never left. I fell in love with the Southwest right then and there—Arizona, New Mexico, all the way down into Baja where the desert smashes against the ocean and both of them don’t give a damn about you. It was the last honest thing left in this country. Raw. Untamed. Romantic in a way that broke your ribs open and dared you to breathe. Even thinking about it now, my eyes light up, my mind drifts, and I can’t help but smile. But hell, I’m drifting again—this wasn’t supposed to be a love letter to sand and dead highways.

I was seventeen, standing in a massive, piss-smelling room lined with other terrified boys, all of us dropping our drawers, bending over, spreading cheeks for Uncle Sam. Welcome to the club, kid. After the degradation, they herded us into a room with a propaganda film rolling—Top Gun, would you believe it? Fighter jets, rock music, handsome sons of bitches in mirrored sunglasses. None of it made any damn sense to me. I didn’t know what I wanted to be. I just knew I didn’t want anything with “combat” in the title. That wasn’t me. That was for guys with death wishes. I leaned over to the recruiter, pointed at some guy wrenching on a jet engine, and said, “Who’s that guy?” He said, “That’s an Aviation Machinist’s Mate.” Perfect. Sounded mechanical, sounded safe, sounded just detached enough for a kid who didn’t know what the hell he was doing.

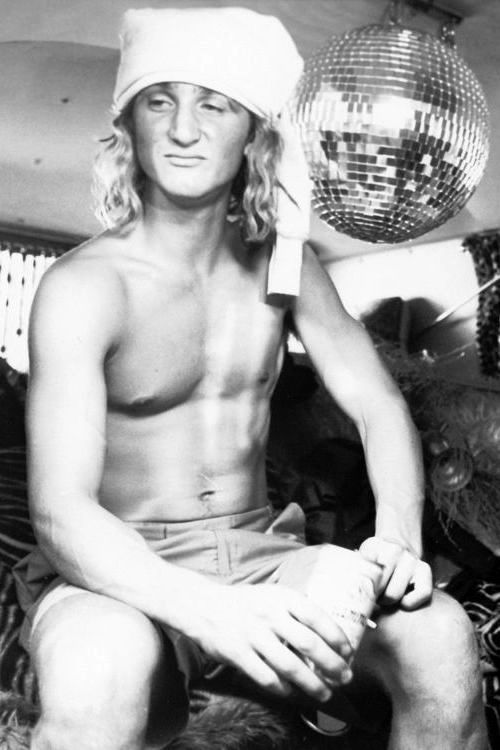

That’s how I became a superhero in my own head—an Aviation Machinist’s Mate in the U.S. Navy. Not exactly Tom Cruise. No jets to fly. No beach volleyball tournaments. Just grease under the nails, long nights, and the slow, grinding realization that being a man was a hell of a lot less glamorous than Hollywood had promised. But the money started rolling in, the maturity started creeping up my spine like ivy, and the balls finally dropped heavy between my legs. Bedposts collected their notches. Women came and went, like bar tabs and bad decisions. I felt more manly, more invincible, more stupid with every passing night.

So, of course, I thought: Do I get a motorcycle? Some shining, humming bullet between my thighs like Tom Cruise’s Ninja, slicing through the world like it owed me something? I went out to a car show in Los Angeles with my dad and brother, wandering aimlessly until I saw it—this Honda CBR gleaming like sin itself. I straddled it, thick arms, broad shoulders, 210 pounds of cocky, half-drunk testosterone. My brother took a picture of me sitting on that thing like it already belonged to me.

It felt good.

Too good.

It felt like an extension of my cock.

It felt like the last piece of the outlaw costume snapping into place.

But I never turned the key. Never felt the engine roar. Never tasted the wind through my teeth. Because the one part of me that wasn’t completely stupid—the small, sober part curled up in the back of my brain—screamed no.

Loud and clear.

NO.

The part of me that had raised myself—the kid who had watched himself nearly drink and drug his way into the gutter—knew the truth: if I threw my leg over that bike, I’d be dead inside a month. No second chances. No hospital stays. Dead. I was already gambling with enough of my life—booze, drugs, women, stupidity. And when it all inevitably exploded, I turned it into some drunken, self-deprecating story to laugh over later. But there’d be no laughing if I cracked my skull open on some highway. No joke to tell when they scraped me off the pavement.

I knew it.

I said no.

And somehow, I stuck to it.

Even when I retired, even when the itch came back, even when I wanted it more than anything, I didn’t buy the goddamn bike.

Bought a Land Rover instead.

A cage.

A compromise.

Even now, all these years later, I still want one. I still want to feel that machine rumble between my legs and pretend I’m free. But every time I think about it, the same voice reminds me: you wouldn’t make it. Not you. Not the way you’re wired.

The only thing that makes me nervous now is that my son rides a bike. I don’t fear for him the way I feared for myself—but there’s always that shadow, that little gnawing thought in the back of my head. The thought that sometimes taking chances is beautiful—and sometimes it’s just fucking stupid.

I took my chances in other ways.

Worse ways.

Wilder ways.

Maybe more cowardly, maybe more tragic.

But at least I’m still breathing.

For better or worse.