Walking Out of TSK and Burning Bridges

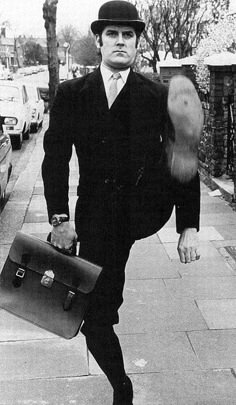

I had the warehouse set up exactly the way I wanted it. Every tool had its place, every part stored in its proper bin, every document filed so that I could retrieve it in seconds. My technician followed my commands without question, a well-trained extension of my will. Yotaka, my quiet but efficient purchaser, handled the logistics, keeping materials flowing in and out without issue. The front desk lady had one job—to answer the phone, take messages, and make sure nothing slipped through the cracks.

We processed over $36 million in probe station equipment every year. Machines like the U200, the U300, and the APM90 were all under my watch, and our inventory reached over $100 million, most of it housed in a third-party warehouse at Nippon Express. They stored our equipment for a fee, and I made sure we paid just enough to keep it running efficiently but never enough to make them rich. Everything ran smoothly because I had my hands on every part of the operation. I designed mechanical interfaces that brought in over a million dollars in new revenue each month, custom testing fixtures, docking solutions, head stage modifications, stainless steel fabrications—whatever the customer needed, I built it. The manufacturing side alone generated $700,000 a month, and I managed every piece of it.

My days were long. Ten, twelve, sometimes fourteen-hour stretches. But I loved it. There was a satisfaction in knowing exactly where everything was, in seeing a well-run machine operate without failure. Every customer request, every order, every design was committed to memory. If someone asked for a part, I could tell them where it was without looking. I lived and breathed that warehouse. Ninety-five percent of it was seamless. The other five percent was a constant headache, but I handled those problems, too.

And then, corporate America came knocking.

Tokyo Seimitsu (TSK) had run its U.S. operations efficiently for years, using the same Japanese precision and discipline that had made it successful in Japan. But someone higher up decided that in order to expand, they needed an American face to represent the semiconductor division. Maybe they thought it would help sales. Maybe they wanted to westernize the brand. Maybe they were just idiots. Whatever the reason, they brought in a new president, Larry Ross, a man with polished fingernails and an empty, plastic smile.

Larry, in his infinite wisdom, decided that his first order of business was to hire another American to run operations. That’s how Jim Anderson entered my life.

I had met Jim years before, at a standardization seminar in San Diego. He had been leading a discussion on interfacing solutions, something I had already mastered, and during a break, I had shared my ideas with him. I had solutions to problems he was supposedly trying to solve. He barely acknowledged me. Dismissed me outright. Didn’t even pretend to listen. That was Jim. A corporate suit who only cared about solutions if they had his name attached to them.

Now, years later, here he was. And I had to answer to him.

Jim wasn’t just incompetent—he was a joke. It started at the Christmas party. The Japanese executives brought their wives, soft-spoken, traditionally dressed, elegant. Jim, in contrast, showed up with a Puerto Rican woman who looked and acted like she had just walked out of a nightclub. Tattoos covered her arms, her dress was three inches too short, and she carried herself with the confidence of someone who had never been told no in her life. If she wasn’t an escort, she was playing the part well.

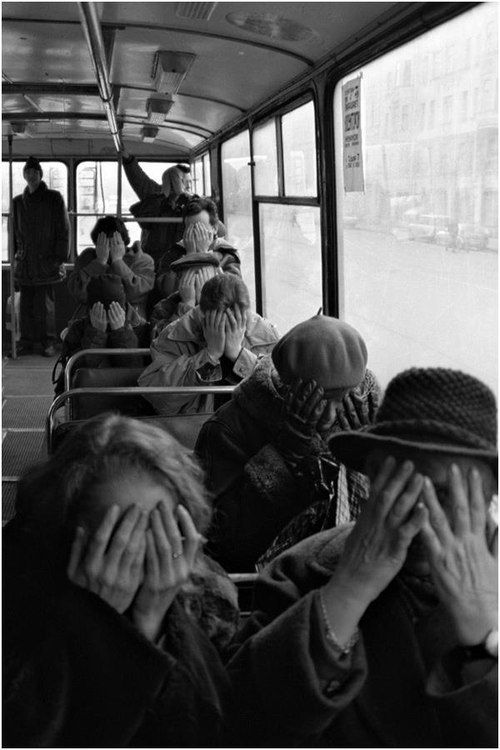

The executives whispered among themselves. They didn’t like Jim. They didn’t like what he was bringing into the company. But at this stage, their hands were tied.

I didn’t like him either.

For the first few months, he focused on reshaping the company, making changes that didn’t need to be made, putting his name on projects he had no involvement in. The usual corporate nonsense—shake things up, rebrand the same ideas, make sure everyone knew who was in charge. And then, eventually, his attention landed on my warehouse. The manufacturing hub I had built from the ground up.

Now, mind you, my title was Mechanical Engineer, and I had every reason to believe I was next in line for Office Manager or Operations Manager. I had run the place for years. Knew it inside and out. Made them millions. This wasn’t me hoping for a promotion—I had earned it.

Then came the meeting. The one where I should have seen it coming.

Jim called me into his office, sitting behind a desk that, if things had gone right, should have been mine. He didn’t recognize me from San Diego. Didn’t remember brushing me off at that seminar. Didn’t realize I was the guy who had handed him the standardization blueprint he now claimed as his own. No, he just looked at me like I was a cog in the machine that needed adjusting.

He asked for my resume, scanned it over, nodded like he was impressed, then leaned back in his chair.

“This is an impressive resume,” he said. “But I don’t see any formal education.”

That motherfucker.

My Mormon upbringing screamed inside my head, demanding I swallow my pride, show some humility, nod along, and pretend I respected him. But I didn’t nod. I didn’t say a damn thing. I just stared at him.

He paused like he was waiting for me to defend myself.

I didn’t.

“You’ve done a fine job getting things to this point,” he continued, like he was delivering some kind of compliment, “but we need to move you out of the quarterback position and let someone else fill that role.”

I stared at him, willing myself not to laugh. This was not how I had imagined this conversation going.

But he wasn’t done.

“We’re bringing in someone new to run the department,” he said. “Your technician, actually. The one with the Master’s in Business. We think he’s got the right qualifications to take over.”

I blinked.

They were giving my job to a technician.

A guy I had hired.

A guy who had been a landscaper before I trained him.

Jim was still talking, probably feeding me some bullshit about how this was a strategic move, how I was still valuable, how there were other opportunities for me within the company.

I wasn’t listening anymore.

Instead, I was listening to the voice in my head, the one screaming at me, over and over again, that I had built this department. Years of my life poured into it. Every workflow, every efficiency, every goddamn improvement that made this company money—it all came from me. I had optimized manufacturing, I had handled customer relations personally, I had turned this operation into a well-oiled machine. And now, some MBA with a landscaping background was taking over because I didn’t have a degree?

Jim, still buttoned up in his polished suit, wrapped up his little speech and looked at me, expectant. Like I was supposed to thank him for this incredible opportunity to be demoted in my own house.

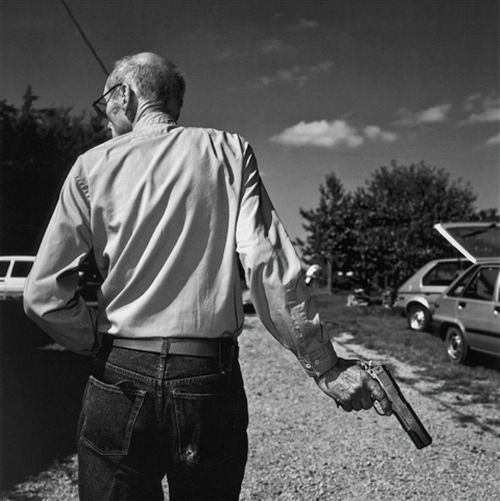

I could feel the heat rising in my chest, my vision tunneling. I leaned in, voice steady, full of something deeper than anger—conviction.

“Go fuck yourself, I quit.”

Not what he was expecting. His jaw tightened, but he didn’t move, just stared at me. I turned to walk out, fueled by a rush of adrenaline, by the righteous satisfaction of telling him off—until his voice stopped me at the door.

“You have a family,” he said, casual, like he was tossing me a bone. “You should think about that before making emotional decisions. Maybe just give notice, take some time, think it over.”

For once, he was right. And he was also playing me.

I had no backup plan. No job lined up. My home life was already a fucking disaster—the silent war with the kid’s mother, the tension so thick it felt like I was suffocating inside my own house. Finances were tight. Mortgage payments looming. Maybe walking out with nothing wasn’t the smartest play. Maybe, just maybe, I should buy myself a little time.

I exhaled, let the rage settle, and sat back down.

“I overreacted,” I said, swallowing the words like glass. “I apologize.”

It didn’t matter. The damage was done.

I spent the next few weeks avoiding Jim as much as possible. I stopped answering his emails, refused to CC him on customer correspondence, and ignored his calls. But the resentment kept growing. The customers still called me directly, not him, and that ate at him. He needed me. And I knew it.

Then one day, while scanning the classified ads in the newspaper, searching for my next move, I saw it—three separate job postings under the company name I had just walked away from. Drafter. Mechanical Engineer. Manufacturing Engineer.

That son of a bitch was replacing me with three people.

It wasn’t even a question anymore. I was done.

I went back to the office with a clarity I hadn’t felt in weeks. Sat at my desk. Stared at the screen. Then, methodically, I wiped my hard drive clean. Every file. Every drawing. Every document I had ever created. Gone. But before I did, I burned everything onto CDs—all of it. Every blueprint, every system I had built, every workflow they were about to hand off to a group of clueless replacements.

Then, I packed them up. Dumped them all into a huge black trash bag, walked out back, and tossed it into the dumpster behind the building.

I sat in my car for ten minutes, staring at that dumpster.

And then, without fully knowing why, I got out. Walked back. Pulled the bag from the trash.

I didn’t know what I was going to do with it.

But I knew this wasn’t over.

The next morning, Jim showed up at the office. I walked into his room.

“This is my last day,” I said.

He barely looked up.

“Good luck out there.”

I walked out of that building for the last time, leaving behind everything I had built. My desk was spotless. The last two weeks hadn’t issued purchase orders to keep production rolling, I had stopped designing, leaving over three million dollars’ worth of engineering work sitting there, unfinished, waiting to be drafted. My desk was clean. My files on the server were even cleaner.

There was nothing left for me there.

I went home and told the kids’ mother that I had quit.

Ahh. There was no support. No excitement. No “we’ll figure this out together.” Just that cold stare. That quiet judgment. That slow unraveling of something that had already been dead for years.

I had left TSK.

And for the first time in a long time, I had no idea what was coming next.