The thing about marriage is that it always starts with good intentions, like a dog you bring home from the shelter thinking it just needs a little love, a little patience, a little training, but before long, it’s pissing on your floor, tearing up your furniture, and staring at you like it’s about to bite your goddamn face off. That’s marriage. That’s why men like me and my organic father—”organic” because he was the real one, not a stepfather, not a replacement, just the man who gave me half of his DNA and all of his regrets—had to find ways to escape it.

And for us, that escape was Baja. Specifically, Los Barriles, Mexico. A sleepy little fishing town where time moved slower, the air smelled like salt and cheap tequila, and the only things expected of you were to drink, fish, and avoid getting murdered by banditos after sundown.

We told our wives we were going fly fishing. We even packed the rods. But we knew, deep down, that wasn’t why we were going. It was about breathing again, about getting away from the thick, suffocating air of our homes where everything had a price—our time, our attention, our dignity. The sunrises in Baja didn’t ask anything of you. They just existed, throwing long pink fingers across the ocean while you sat on the rooftop of some half-crumbling stucco house, drinking strong Mexican coffee and watching fish leap from the water like they were celebrating their own freedom.

And for a few hours, you could convince yourself you were celebrating too.

Until the real world, and the real bullshit, came creeping back in.

That day, we decided to fish the East Cape. We took a shitty Avis rental Jeep, the kind they give gringos who are dumb enough to think four-wheel drive is optional in Baja, and drove out past some dusty little cow town. Pulled over, put on our gear—flip-flops, shorts, fishing vests that made us look like rejects from some washed-up Hemingway novel—and started walking the beach.

The sand was white, soft, stretching endlessly in both directions. About six feet out, the ocean floor dropped into a deep blue abyss, the kind of water that swallows men whole if they’re stupid enough to underestimate it. That’s where the big fish were—the ones that made the trip worth it. The roosterfish, prehistoric and ugly, with a dorsal fin that stuck out like the mohawk of a punk kid who never grew up.

We walked. We cast. We reeled. We walked some more. The sun bore down like a vengeful god, baking the salt into our skin, bleaching our clothes until they looked like relics from another century. We had been out there for hours when we saw the bait ball—a frantic, writhing mass of tiny fish pushing toward shore because something bigger, meaner, and hungrier was chasing them.

A roosterfish shot through the water, its fin slicing through the surface like a blade, its body torpedoing into the bait ball. It was beautiful. It was everything we came for. We cast like maniacs, arms burning, sweat dripping, watching as the ocean turned into a feeding frenzy. And after all that effort, all that perfect goddamn timing, we caught nothing.

Not a single goddamn thing.

We kept going, kept walking, kept casting, because what else was there to do? We had come this far. We had invested too much. Six more miles down the beach, and by then, we looked like we had been stranded for days. Lips cracked, skin blistered, eyes sunken and burning with that feral, salt-ridden exhaustion that turns men into animals.

That’s when we saw them.

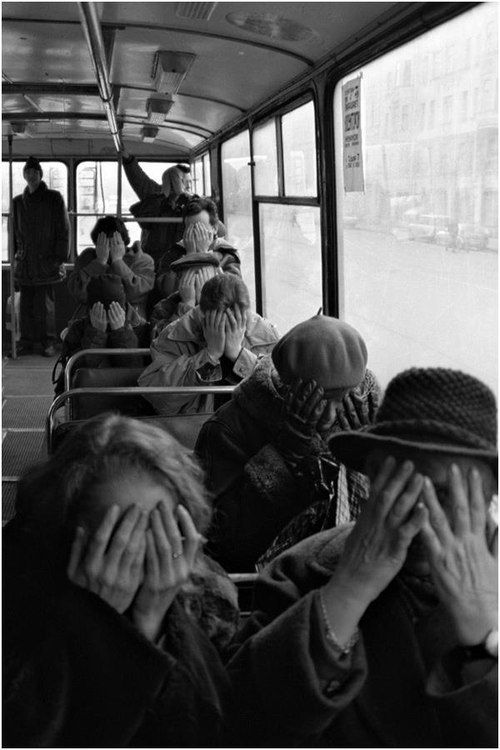

Another father and son, coming toward us from the French colony down the coast, looking just as wrecked as we did. Same setup. Same mission. Same failure. They hadn’t seen a single roosterfish either. We stood there, looking at each other, at these strange mirror versions of ourselves, and in that moment, we understood something:

Some pursuits are noble, but they will ruin you.

We turned around.

The sun was setting by the time we got back to the Jeep. And that’s when it happened.

I grabbed a beer—because priorities—and my father went to unlock the driver’s side door. He threw the keys on the dashboard, and we both watched, in drunken, slow-motion horror, as they slid into a crack behind the dash.

Gone. Just like that.

A silence fell between us.

I finished my beer and tried to reach for the keys with my fingers. Nothing. He tried using a hook and some string. Still nothing. The sun had dipped below the horizon, and suddenly, all those warnings about not being out after dark started ringing in my head.

This was bandito hour.

The cows wandered in, chewing on old cement bags. A group of locals were drinking around a fire, watching us with the quiet amusement of men who had seen enough stupid gringos in their lifetime. My father, desperate, went over to ask for help. They laughed in his face.

So I did the only logical thing.

I started digging a hole under the Jeep. If we were going to die out there, I was at least going to have a goddamn bed.

Eventually, a teenage kid showed up. He assessed the situation, reached in with his tiny, grubby little hand, and popped the keys out with no effort at all. Just like that.

We were free.

But we weren’t safe yet.

The drive back was slow. Baja at night is not a place you speed through unless you want to become a smear on the road courtesy of a half-ton cow standing in the darkness like a drunk waiting for a fight.

We made it back to Los Barriles and went straight to Buzzard’s Grill. Sat at the bar, two men who had barely escaped death-by-idiocy, and drank tequila like we had just cheated fate. We tried calling Avis to let them know we weren’t stranded in the middle of nowhere anymore, but of course, the line was dead.

And then, on our way back to our rental house, it happened.

A roadblock.

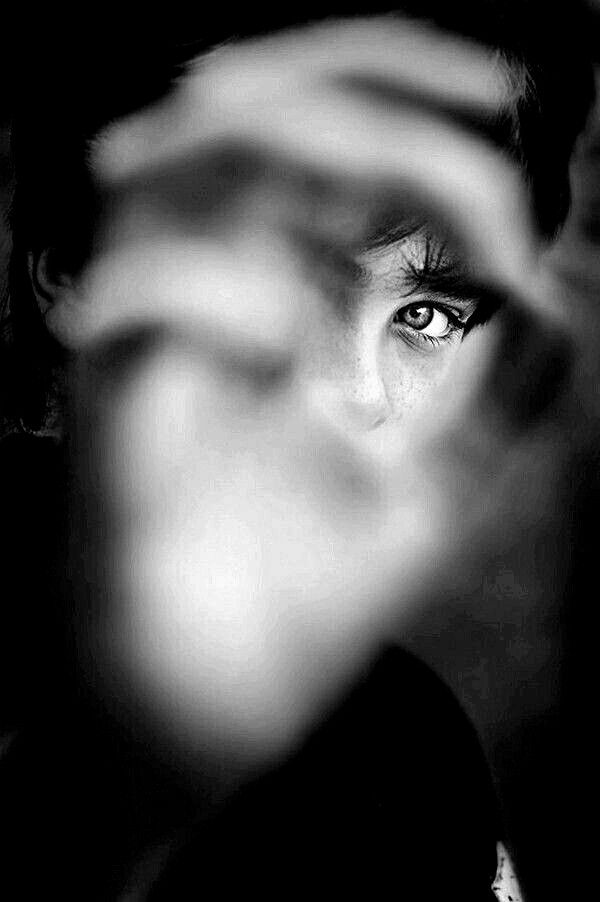

High beams hit us from every direction. Shadows moved in the glare. And then, out of the darkness, figures emerged—Mexican military, carrying machine guns, closing in on us like we were the main attraction at a firing squad.

One of them, a commander by the looks of his uniform, leaned into my window.

“Do you speak English?”

I shook my head.

“No Español.”

He sighed, like he was already exhausted by my bullshit. “No, I asked if you speak Spanish.”

I grinned.

“Nope.”

That got a chuckle from him, but we were still surrounded, still at gunpoint, still sitting there with tequila-soaked brains trying to figure out if this was the moment we got buried in a mass grave somewhere.

Then, out of nowhere, a truck full of real criminals rolled up.

Their attention shifted instantly. They swarmed the truck, guns raised, shouting in Spanish. The commander looked back at us and gave a single order.

“Leave.”

We didn’t argue.

The next morning, we walked into town to get breakfast, and there they were. The men from the truck. Their faces were swollen, bruised, eyes vacant.

We never caught a roosterfish.

But we did catch a glimpse of how close we came to something worse.

And that, somehow, made the whole trip worth it.