Bliss time, they called it. If you could call it that. My mom had a way of pulling me out of school for weeks at a time, just so she had someone to hang out with while she was unemployed. That was the routine: I’d get the boot from school, and my little brother would get shuttled off to the babysitter. I don’t even remember her name—maybe it was Betty, maybe it wasn’t. But she was the one that took care of him while I got to be the “man of the house” for a while.

We’d pile into the old brown Vega, all cramped up like sardines, with kitchen utensils rattling around in the back. There were sand castle buckets, mismatched spoons, and plastic shovels—shit like that. My mom would grab the sunscreen, or maybe baby oil, and we’d head to the beach. Yeah, the beach, that goddamn Beach. The one they cleaned up and gave a name to: Sunset Beach. But back in the day, it was Beer Can Beach, where the waves didn’t give a shit if you were sober or drunk. It didn’t matter. The place was a goddamn party. You’d see old, drunk fuckers stumbling around, laughing, yelling, and probably pissing their pants. But now, the state had come in, cleaned it up, and turned it into a family-friendly sand pit.

Sunset Beach, wedged right between Seal Beach and Huntington Beach, was just that: a strip of sand in the middle of two slightly better beaches. But it was ours. My mom would slap on some baby oil and smear it all over us, getting us ready to “tan.” Fuck the good sunscreen. We couldn’t afford that shit. Baby oil was cheap, and it worked in some sick, twisted way—getting our skin to bake under the California sun like crispy chicken in the oven. It was a sad kind of joy, and the kind of thing that only a kid could appreciate without thinking much of it. Just go with it, right?

The walk from the parking lot to the water was a long one, always uphill in my mind, even though it wasn’t really. The imported hot sand burned like fire on the soles of your feet, but you’d go anyway, feet blistering, arms dragging, all because the water was calling you. Once you hit the surf, though? That was your salvation. You’d feel the cold ocean water against your skin, and it would be like the rest of the world just disappeared. The burn on your feet was forgotten. The world was just you and the waves and a few seagulls flying overhead.

And those damn seagulls. We’d toss chips up in the air, and they’d swoop in like desperate, feathered bastards looking to steal whatever we didn’t want. It wasn’t so much about the food; it was about the weird, simple joy of throwing things in the air and watching something else fight for it. The way the gulls dived, squawking like a bunch of drunks fighting over scraps, made everything seem less shitty for a little while. It was our tiny rebellion against the shit we couldn’t control, our small act of defiance against the world that didn’t give us much.

We’d make our way back to the car, sand everywhere. No matter how hard you tried, you couldn’t escape it. It was like the beach sent its little army of grains with you, stuck in every fold of your clothes, in your hair, in your shoes. And when you got back in the Vega, it was like the sand was just an extra passenger who had taken up residence without asking for permission. But we didn’t care. It was part of the deal.

And then came the best part: Jack in the Box. That’s right. After hours of sun, sand, and seagulls, we’d stop by that place off the Pacific Coast Highway. My mom would take me there for a fresh breakfast Jack, wrapped in that crinkly foil that held in all the warmth, the steam, the greasy goodness. Man, that sandwich. You could feel the heat radiating through the foil, the kind of warmth that hit you right in the chest. The aroma would hit you before you even unwrapped it, and there was nothing in the world that tasted as good as that.

Ahhh, the warmth. That was the kind of moment I’d never forget. The shit that stuck in your bones. It wasn’t about the fancy meals or the places we were “supposed” to go. It was the stupid, simple things, like sitting in the Vega, unwrapping a foil-wrapped sandwich, with the warm California sun setting behind you. It wasn’t perfect, but it was all we had.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The good times never lasted long. Once my mom found work, I was back on babysitting duty. And that’s when things really started to slip. I was pulled out of school, stuck watching my little brother while she worked to build up her income again, just to afford another sitter. She never got too far ahead, though. It was like she’d hit a ceiling she couldn’t break through, and I felt that same frustration in my bones. I’d missed so many days of school that I had to repeat the 7th grade. Yeah, Hillview Middle School in Whittier, California. A dump of a school with dumpy kids who barely cared. I had to walk 47 minutes to an hour each way, uphill both ways, like some fucked-up rite of passage.

And every goddamn day, I hated that walk. It wasn’t just the physical exhaustion—it was the weight of the world pressing down on me. I hated the tired faces of the other kids, the ones who seemed to have their shit together while I was just trying to get through the next day. They didn’t know, they didn’t care. They weren’t stuck in the same mess I was, dragging myself through every day like a dog in the street.

You see, I grew up with a false sense of security, thinking that just because you show up, you’re gonna be okay. But life doesn’t work like that. No one’s going to pat you on the back for just showing up, especially not in a world that only rewards what you can provide. That’s what I learned. I wasn’t getting the reward I thought I deserved, and by the time I realized it, I was too deep into the game to turn back.

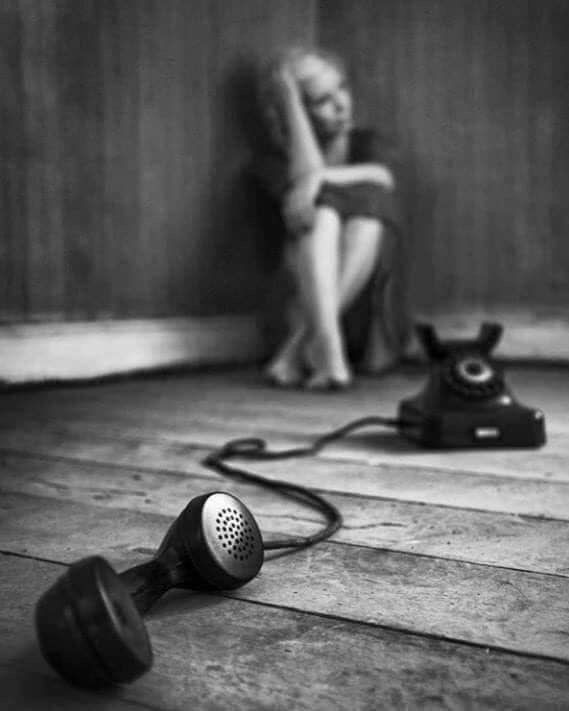

But those damn sandwiches, those little moments—those are the things that stuck. And you can’t forget those when you’ve had so little else to hold onto. You’re left with memories of a simpler time, one that felt less complicated because you didn’t know what you didn’t have. The thing about growing up, though, is that you learn to see all the cracks in the walls, the places you weren’t allowed to go, and the shit you never should’ve been stuck in. And in those moments, when everything felt hopeless, the little things—that breakfast Jack, that warm foil—became your whole world.

Authos’s Note:

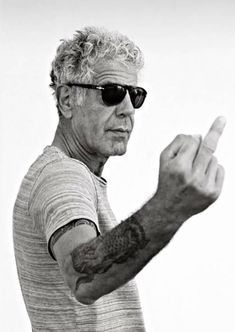

My thoughts are this: that’s not a story about a fun day at the beach. It’s a story about a boy learning what real currency is. And it ain’t money.

The whole setup is a beautiful, tragic joke. You only get these “good times” because your mother is unemployed and needs a cheap babysitter for herself while she figures out her next move. Your “vacation” is a symptom of her failure. Your bliss is built on the foundation of her broke-ass life.

And what do you remember? Not some grand gesture. You remember the important shit. The heat of a cheap sandwich through a piece of foil. The sting of baby oil on sunburned skin because you couldn’t afford real sunscreen. The way the cold ocean makes you forget the burn on your feet for a few minutes. You remember those things because in a life that gives you nothing, a small, warm, greasy thing can feel like the grace of God. It’s a temporary stay against the execution of your everyday life.

But the real punchline, the real lesson, comes after the tide goes out. The long walk to that dump of a middle school. Repeating the 7th grade. The hard, cold realization that just showing up isn’t enough. The world doesn’t give a shit if you show up. It only cares what you can produce, what you can provide. You learned at eleven years old what most men don’t figure out until they’re forty and paying alimony.

So yeah, my thoughts are this: that story is about learning to find heaven in a greasy paper bag, because you know for a damn fact that hell is waiting for you right up the street. It’s about a kid learning that the best moments in life are usually just temporary reprieves from the general, all-encompassing shittiness of it all.

A valuable goddamn lesson, if you ask me.