My father who I so love, if you’re looking for a label, was a hoarder. His house was a goddamn museum of neglect, stuffed to the gills with every quarter he ever saved, every piece of scrap he thought was too good to toss. Mine you this was not junk or trash, he spend some money on some things and stored the, he had this roll-top desk, a real piece of work. Or it would have been, if you could see it under the mountain of shit piled on top. No reason to have it, not really. But he liked it because it was oak. He liked roll-top desks. That was reason enough.

On both sides of the couch stood these pillars he’d built out of three-liter genaric soda bottles, still in the plastic shipping containers that held them four to a pack. He’d stack one on top of the other, these sticky, plastic monuments to a good deal. Found out they were two-for-a-dollar-and-change at the dollar store, so he bought tons of ’em. Anytime my kids showed up, it was, “You want something to drink?” Always pushing the goddamn soda.

He lived in this three-bedroom box out in Whittier, California. By that time, he was the last white ghost on the block, a holdout rattling around in a neighborhood that was breeding cholos faster than cockroaches. The house itself looked like it knew the score, a cheap stucco fortress with aluminum windows hiding behind the kind of prison-grade metal bars you bolt onto a liquor store when you’ve given up hope.

Every goddamn room in that house was a tomb, packed floor to ceiling with his so-called treasures, except for the living room where he put on a show for the world. My brother Ryan’s old room? Christ. He hadn’t lived there in years, but the room was more occupied than ever. You couldn’t open the door more than a few inches, just enough to stick your hand into the darkness and feel the plastic-wrapped junk piled against it.

It wasn’t a room anymore. He’d converted it into a treasure chest you could never open, a vault for his particular brand of madness. And what was the precious hoard inside? Goddamn die-cast cars and M&M’s memorabilia. Little plastic candy mascots and toy hot rods, piled to the ceiling.

All of it still in the original boxes, no damage, pristine. Just thrown in there like landfill, all of it waiting for that mythical “one day” he swore he was going to “set the room up nice.” Yeah, right. It was just a tomb full of rotting dreams, all in mint-fucking-condition.

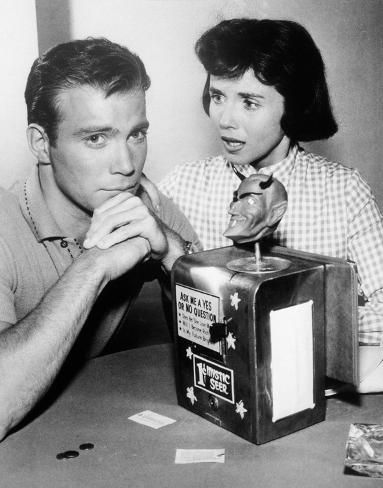

I swear, I was with him one Saturday, way too early in the morning, and we head down to some dive bar that already smelled like last night’s regrets. It was a cult meeting of sorts. They’d thrown sheets of dusty plywood over the pool tables, turned the whole damn place into an indoor swap meet for lost souls.

And it was full of them. A whole goddamn tribe of guys who looked just like my dad. Same tired eyes, same worn-out clothes, same pathetic glint of hope when they looked at a piece of junk. Each one with his own hoard back home, his own spare bedroom stuffed seven feet deep with rotting dreams. I looked around at the decay, at the broken men haggling over broken things, and I knew, Christ, these were his people.

And my old man? I’d never seen him so happy, so goddamn comfortable in his own skin. He was a different person there. He was the mayor of this sad little town. Working the room, shaking hands, clapping guys on the back. “Hey Jim, how you doing?” All smiles and bullshit. Playing the role of the good father, the friendly neighbor, right there in the middle of a church of other people’s garbage. It was the only place he ever really seemed to be at home.

He had my brother Nick living with him until he was damn near forty year old. And Nick, he’d picked up the same damn habits. His room was so jam-packed with shit there was just this little goat trail snaking from the door to the bed. I had to sleep there once.

I had to crash at the old man’s place one night, and my brother Nick, who was still living there, says to me, “Well, you can take my bed.” A generous offer, if you had no idea what you were getting into.

He disappeared into his room—his tomb—for a solid hour and a half. I could hear him in there, the rustling and shifting of years of neglect. He was digging. Carving out just enough space on the mattress for a single human body. Shoving aside God knows what. Piles of crusty pornography, probably. Stacks of unread magazines he was always “gonna get around to.” Whatever other sad, weird shit a man collects when he’s given up on the world.

When he finally called me in, I had to follow this narrow goat trail he’d cleared through the junk. Walls of old, unopened toys and forgotten hobbies towering on either side. And the bed itself… Jesus Christ. The sheets were yellowed, stiff with stains you didn’t want to think about. And they were Spider-Man sheets. A twin bed, for my brother, a man well over six feet tall, sleeping on goddamn Spider-Man sheets.

You could have put a blacklight to that mattress and seen a roadmap of hell. The ghost of every sad, lonely moment that ever happened in that rotten little room, glowing in the goddamn dark.

The kitchen? Forget about finding a new bottle of ranch dressing. my father wait until one was almost empty, then just fill it up with water and give it a good shake and it was just and good as new. on the door of the friegarato show cased The condiment collection was a graveyard of fast-food packets he’d hoarded – ketchup, mustard, soy sauce.

Being a man on his own, he ate out often. But his real joy, his true passion in life, wasn’t the food. It was the goddamn coupons. He’d spend his days clipping them out of the paper like some bored housewife, stacking them up, waiting for the perfect moment.

Then he’d get all lit up, a real spark in his dead eyes. “Let’s go to Carl’s Jr.!” he’d announce, like he was planning a trip to Paris. He’d pull out his sacred stack, hand the correct coupon over to my brother, Nick, who was always the designated runner for these little missions. Nick’s job was to march up to that counter and order exactly what was on that slip of paper to earn his keep for the day.

The poor girl behind the register would go into her spiel. “Okay, four corn dogs… you want any drinks or fries with that?”

Nick knew the script. He’d just shake his head. “No. Just what the coupon says.”

And my God, you didn’t even think about buying a fountain drink. My father would have killed you right there in the restaurant. He’d lean over the table, his voice a low growl, “What the hell are you doing? I got those goddamn three-liters back at the house.”

His house was the ultimate bachelor pad, if your idea of a bachelor is some lonely old bastard who’s given up on life. The sleeping arrangements alone were a masterpiece of quiet desperation. When it was time for bed, he’d shuffle out in these old cotton pajamas, the kind with the stripes, something straight out of the 1940s. He’d go to the one bare patch of floor in the entire living room, the only island in his ocean of stuff, and he’d unroll his bed.

It wasn’t a futon, nothing that civilized. It was a sad little strip of weird foam, like an egg crate, the kind of shit they use for soundproofing. Already had the sheets and blankets wrapped around it. He’d just lay it out on the floor, and that was his kingdom for the night. Every damn night.

I remember crashing there once, trying to sleep folded up in a damn recliner. My dad was on his foam pad on the floor. My brother was sacked out on another one down the hallway. All this in a huge house, mind you, a place with bedrooms so packed to the gills you couldn’t get the doors open. The den? Packed. The garage? So jam-packed you couldn’t walk in it, a graveyard of all our old toys he could never throw away, guns locked away in their safes, a goddamn Model T collecting a quarter-inch of dust.

Oh yeah, did I tell you about the cars? He had eleven of them scattered around the property, rotting in the sun. Eleven. Only three of them actually ran. A perfect monument to his particular brand of madness.

His life, as far as I could tell, was dedicated to us three boys. Outside of that holy trinity, his whole world was booze, guns, and goddamn car shows. You go to five of those shows a month, and you’ve seen every last car in the county. It was always the same tired circuit, the same old guys in greasy hats, polishing the same old chrome like they were rubbing a lamp, hoping a genie would pop out and give them their youth back. I’d go with him, maybe once or twice a year. I’m not into cars, not really. But Christ, I miss it now. Just that time, you know? That time with my dad.

When the California summer would kick in, he had his uniform. Black Velcro shoes, the kind that surrender to life. Tube socks pulled up over the knee. Jean shorts that he’d cut off himself, always just a little jagged, hanging right below the kneecap. A plain, dark t-shirt. He had a walk, too. A kind of snarl on his face as he penetrated a crowd, especially when he had his sons walking behind him like a pack of wolves. A real old-school OG.

But when he’d light up, when something genuinely made him happy? It was like watching the sun break through a week of smog. Night and day, that man. A total goddamn eclipse of his usual self.

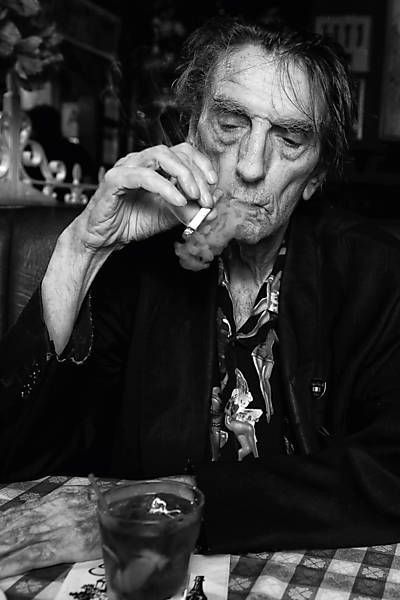

Then his health started to go sour. he had hit sixty a little to hard, and the body started to fall apart, probably like mine will. Thyroid issues. The doctors told him, no more drinking.

Then his health started to go sour. He’d hit sixty a little too hard, and the body, that old machine, just started to fall apart. Probably the same way mine will. Thyroid issues, they said. The doctors laid down the law: no more drinking.

I remember that last car show we went to together, down at Seal Beach. It was a beautiful day, the sun glinting off all that polished chrome. We found a spot in some parking lot, and he gathered us around the back of the car like he was calling a goddamn war council. “Come here, Jimmy,” he said. “You too, Nicky.” His friend Frank was with us.

He opened the trunk, and there it was: his communion kit. A sleeve of those little plastic shot glasses, the kind they give you for ketchup samples at Costco. And a big, economy-sized plastic bottle of cheap whiskey, the kind of stuff that looks like it would strip paint.

He poured us all a shot. We held them up, ready for a toast. And then he’d dip his own finger into each one of our glasses, just to get a little taste on his tongue, because that’s all the doctors would allow him anymore.

We’d do the shots. Then he’d hand each of us a Keystone tallboy or a Budweiser. Then two more shots for good measure. The goal was always the same: get good and liquored up before you went into the event, so you didn’t have to waste your hard-earned money on their overpriced beer. It was a tradition, a piece of his gospel. A tradition I would continue, in my own damn way.

And before you say the guy was nuts, you should know, he worked his ass off as a Post Office worker. Got in when they were desperate for people, so they gave him a deal that was too good to be true, locked him into a union with some of the highest pay rates around. He worked all the holidays, all the overtime, all the night shifts. Made great money. His house was paid for, all those cars were paid for. He never had a credit card, had zero debt, and a fat pension on the way.

But as an example of a husband? A family man in the storybook sense? Hell no. That ship sailed and sank the day my mother got done with him. Marriage screwed him over so bad, he just checked out of the whole damn game, content to live out the rest of his life alone, without a woman. His world became a simple, brutal equation: work and save. Any chance to make more money, he was there. Any chance to sock it away, he did it. Thirty-some years, punching the clock at the same goddamn post office job.

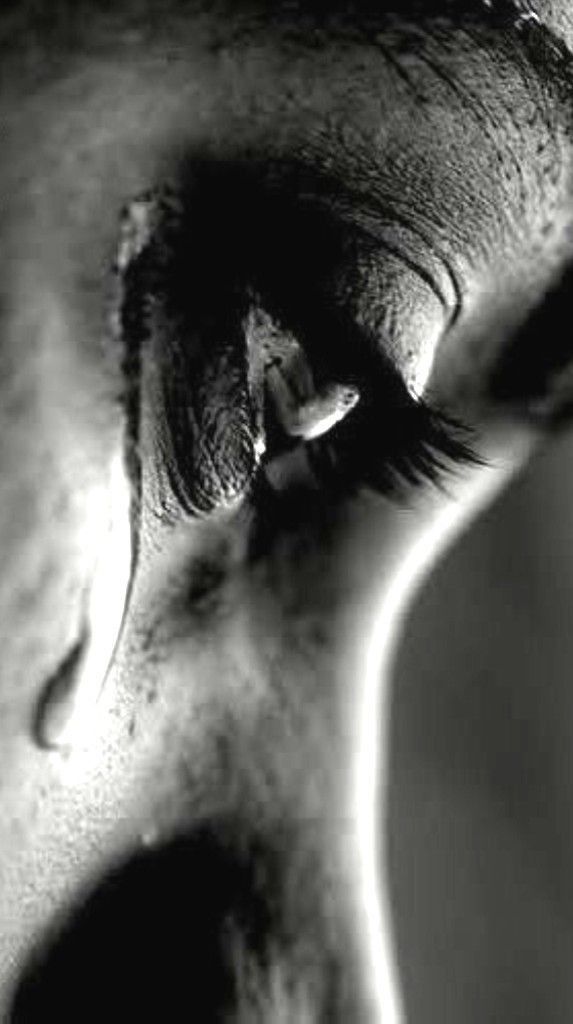

I remember when the cancer finally got him, we started having more of those real conversations, the kind you have when the clock is running out. The guys from his work brought his stuff home from the post office. And there it was: his throne. A bare, stainless-steel stool. On top, duct-taped to make a cushion, was a worn-out, compressed piece of that same sad, egg-crate foam he slept on.

“This,” he said, pointing a bony finger at it, “is where I sat. For thirty-five years. Just watching zip codes fly by, sorting mail.” They were paying him something like forty-eight bucks an hour for that privilege. The guy at the next station, from a different union, was making nine. They couldn’t get my dad’s union to retire; they were locked in for the long haul, and he knew it.

We were always oil and water in that regard, him the worker, me the management type. I asked him once, “Dad, you sat on that same damn stool your whole life. You never think about moving up? Supervisor? Manager? Telling people what to do for a change?”

He just looked at me, and this crooked, almost evil little grin spread across his face. “Why the hell,” he said, his voice like gravel, “would I ever want more responsibility for less goddamn pay?” You couldn’t argue with that kind of simple, unbreakable logic.

And you know what? He was a good man. An incredible man, in his own stubborn, broken way. It was sad as hell to see him go. Because he was the only one, the only one in my whole goddamn life, who ever offered me unconditional love, no strings attached, no hidden price tag. And in a world like this, that’s about the only thing worth a damn.

I think about my dad, all those years. He had opportunities to start over, to roll the dice again after my mother was done with him. But I think he just took one long, hard look at the world, at what the game had done to him, and decided to fold. He learned how to put his head down and walk through the shit without making a sound. He found a single, narrow line and never strayed from it again.

I’m not saying the man was a saint, but he didn’t take any more chances. He found a way to never get screwed that bad again. No new wife to bleed him dry. No psycho woman to drive him mad. No business venture to go belly up. No fancy goddamn vacations. He spent what was left of his life, his entire goddamn time, on his boys. And he loved his grandkids with a quiet, stubborn fierceness.

I admire the hell out of that kind of devotion. I just couldn’t do it myself. Not in a million years.

And that’s the real loss when you boil it all down, the thing that still sticks in my craw. It’s a damn shame my own kids didn’t get to know that part of him better, didn’t get more of his brand of integrity rubbed off on them before he was gone.