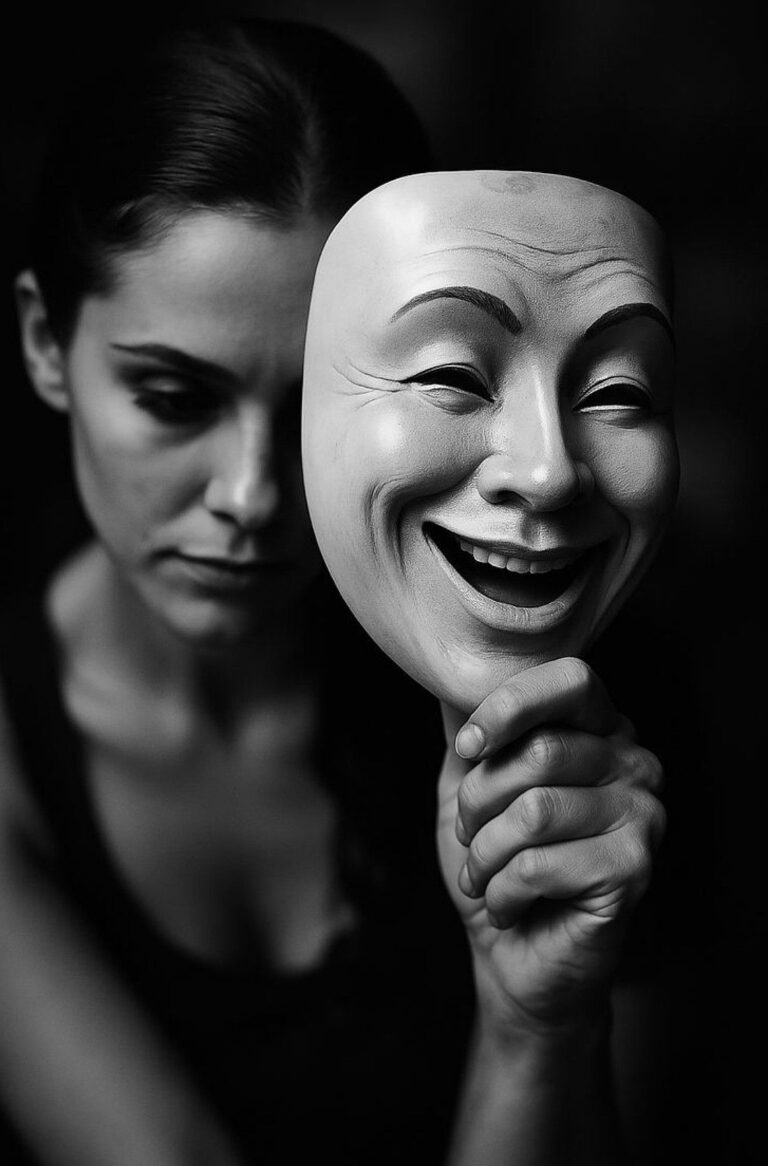

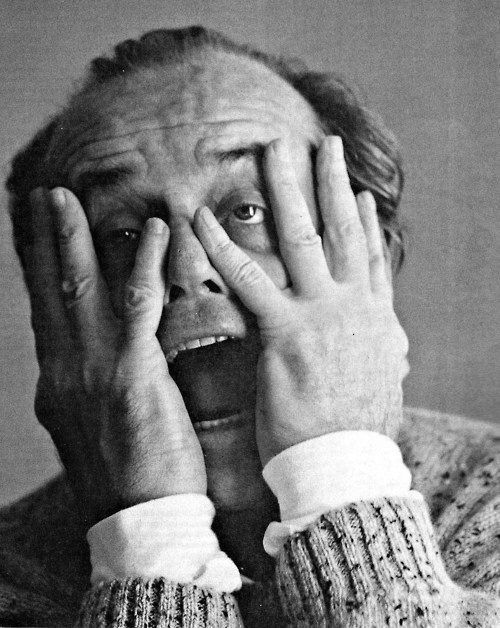

You’re looking at a case study in demolition. My whole goddamn life has been a project built in reverse. I’m a self-made man, alright. I’ve built a new version of myself every ten years or so—the perfect Mormon, the bar-brawling drunk, the Tony Soprano millionaire, the Sedona guru. And every single one of them was a direct, violent reaction against the man I was before, and ultimately, against the scared little kid I was at the beginning.

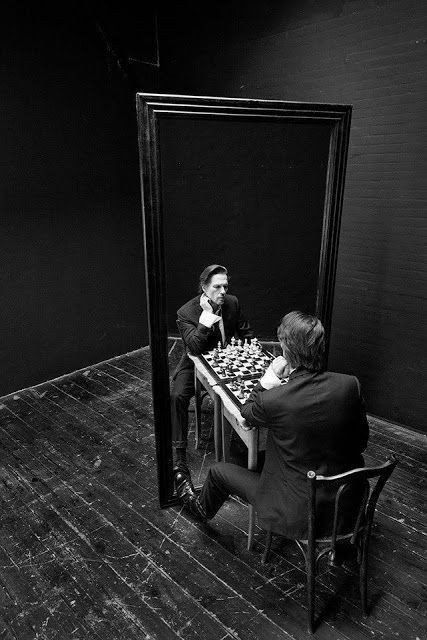

I’m an architect of elaborate cages, designed to keep my own past at bay. And then I spend years rattling the bars, wondering why the hell I feel trapped. My entire life has been a war between two sets of blueprints, handed down by two different fathers: one on how to endure misery, and the other on how to run from it. I’ve mastered both, and it’s left me stranded. A king of a ruined empire, planning one last great escape.

You can’t understand the building without knowing the two men who drew the plans. First, there was Jim, the stepfather. “The Rock.” He was the blueprint for endurance. A man who took the hits, ate the shit, and stayed put in a miserable life out of a quiet, stubborn sense of duty. He taught me that a man’s job is to suffer without complaint, to be a good, solid, and completely dead foundation.

Then there was the biological father. “The Runner.” He was the blueprint for escape. A man who saw the storm coming, signed me away like a bad debt, and ran for the hills in the name of freedom.

My entire life has been a goddamn pendulum swinging between those two impossible poles. I have been both men, and as a result, I am neither.

I didn’t just escape my white-trash, alcoholic past; I tried to obliterate it. The Mormonism, the thirty-hours-a-week of church service, the refusal to drink or even look at another woman—that wasn’t a lifestyle change; it was a desperate act of self-creation. I wasn’t just being a “good man”; I was building a goddamn fortress of righteousness around that scared, abused “Golden Boy” from Whittier. The marriage itself was part of the construction. She wasn’t a lover; she was a load-bearing wall, the “good mother” who was supposed to prove that this new, perfect life I’d built was sound. But when that load-bearing wall cracked over something as stupid and pathetic as a goddamn garbage disposal, the entire phony temple I’d built on top of her was doomed.

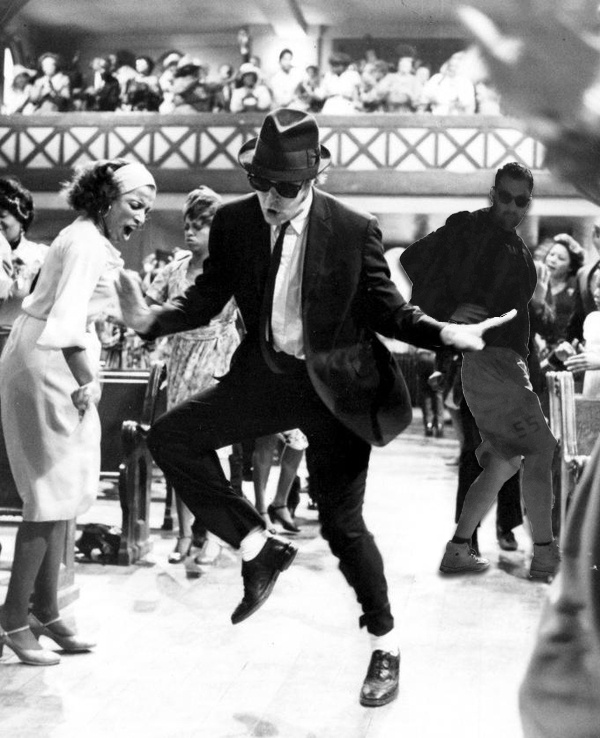

When that “perfect” life imploded, I didn’t just get a divorce; I became the polar opposite of the man I had tried to be. If the Mormon was chaste, this new man was a goddamn libertine. If the husband was a stoic provider, this new man was a drunken, brawling, self-destructive force of nature. The “Tony Soprano” phase, the nine women in 24 hours, the coyote painted on the front of my truck—this wasn’t a search for happiness. This was a demolition project. It was the rage of a man whose carefully constructed reality had been revealed as a sham, and I was taking a sledgehammer to the remaining walls of my own prison.

After hitting the bottom—the profound, ugly loneliness that comes after the meaningless sex, the sober realization that I was the common denominator in my own misery—I pivoted again. Sedona. This was another conscious act of self-creation, but this time, the goal wasn’t perfection; it was purification. The meditation, the hiking, the crying on a hilltop, the “saying yes to everything”—it was a brutal, self-imposed rehab. I was trying to sweat out the poison of my past, to kill the angry animal that had been driving me. And I did change. The anger cooled, replaced by a kind of weary, emotional vulnerability I’d never had before. But as the Hawaii years showed, the old habits—the drinking, the inability to commit, the jealousy—they were still there, lurking under the surface, just wearing a goddamn Hawaiian shirt and a spiritual smile.

So who am I now, at fifty-six? I’m the sum of all these failed constructions. I’m a man who despises manipulation but knows that every goddamn relationship is a quiet power struggle. I’m the lone wolf who built his own empire, but I can still name every sonofabitch who handed me a hammer when I needed it. I’m a man who claims to have given up on love, while planning a meticulous, life-altering quest to find a traditional family on another continent.

I’m not running from a woman or a failed marriage anymore. I’m escaping the entire American system that I feel first broke me, then remade me, then trapped me again. The 9-to-5 grind, the taxes, the empty consumerism—it’s all just a bigger, more sophisticated version of the gilded cage of my marriage.

Argentina isn’t a place; it’s the final job site. It’s my last, great attempt to prove that a man can, in fact, build a genuine life after burning everything else to the ground.

The ultimate question remains the one I can’t seem to answer myself: Am I running to something, or am I just getting better at running away?

I’m betting my entire goddamn life on the former. And for a gambler like me, that’s the only game worth playing.