My grandmother’s beans. Christ. They were a goddamn miracle. I don’t know what kind of magic she put in that pot, what kind of deal she made with what kind of god, but they were the best damn thing I’ve ever tasted. Maybe the only real, honest-to-God love I’ve ever known.

She’d fix me a plate, me and my uncle Brown and my grandfather. She’d put it down in front of me, a mountain of those beans, a little bit of that greasy, perfect Mexican rice, and a few scraps of meat that I never paid much attention to. I was only there for the beans. And lucky for me, she always made a huge goddamn pot.

She’d roll up the tortillas in a towel to keep them warm, and you’d use them to mop up the juice, to shovel in the goodness, a perfect, beautiful, and completely honest transaction.

She was proud of me when my plate was clean, almost licked clean, after three or four helpings. She had her secrets. Sometimes the chicharrón guy would come by, and she’d give him a dollar for a bag of those crispy, fried pork rinds. I’d watch her crunch them up in her hands, a fine, salty dust, and sprinkle them into the pot. Jesus. Absolutely delicious. The woman could do no wrong when it came to food. I never turned down a single thing she ever put in front of me. Everything she made, it tasted of love.

As a kid, I’d sit at her dining room table and help her pick the little rocks out of the dry beans, watching her, trying to learn the magic, hoping that one day, when I was a man, I could make something that good myself.

I never did.

When we’d go on trips, just the two of us, she’d take me on the bus to downtown L.A. She was proud of her bus pass. After my grandfather’s car accident, she didn’t want to drive with him anymore. Never had a license, never wanted one. She’d take me to these buildings that had the elevators on the outside, and we’d ride up, looking down at the big, dirty, beautiful city. And the whole time, she’d have a bag of her bean burritos, wrapped in foil. Every thirty minutes or so, she’d pull one out and hand it to me. They’d be cold by then, but my God, they were still the best damn thing I’d ever eaten.

I got older, got a wife—the one before the crazy got her—and every time we’d visit, my grandmother would make a big deal of it. “Jimmy loves my beans,” she’d say. And I’d eat almost the whole goddamn pot. Then I’d sneak a hundred-dollar bill somewhere in her kitchen before we left. She was never happy about that.

Then I had kids, and it was still about the beans. Always the beans.

She got older. It was harder for her to stand over the stove. I made the mistake once of telling her I was coming over. When I got there, she didn’t answer the door. I walked in, and she was on her hands and knees, trying to pull herself up on the stove to stir the goddamn pot. “Grandma, please,” I told her, “stop.” From then on, I stopped telling her when I was coming.

I’d just show up, knock on the door. She’d be in her nineties by then, usually asleep. I’d let myself in, quiet, not wanting to wake her. And I’d open the refrigerator, and there it would be. A big, beautiful bowl of her beans, waiting for me. To this day, I still haven’t had any beans like that. I’ve failed, in so many goddamn ways, to even come close.

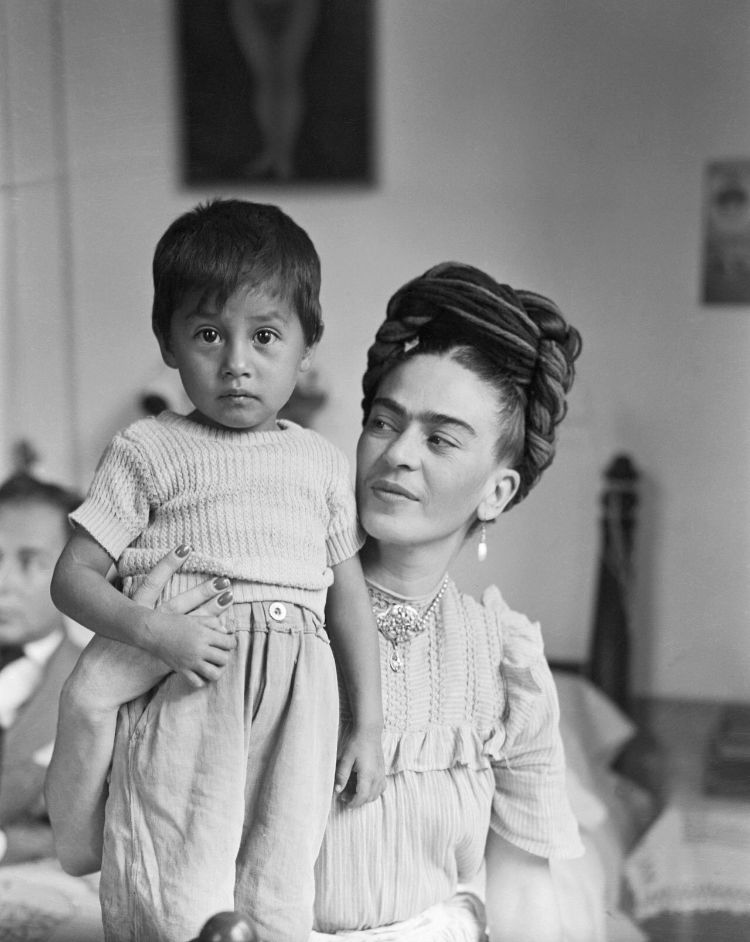

She was an incredible woman. The Oracle of the family. When my grandfather died, she held it all together. When my uncle Brown died, she was the rock. The whole family, it revolved around her. My mom, my aunt Julie—they both tried to be the new Oracle after she was gone, but they were just cheap, polished imitations. My dad’s side of the family, after his mother died, they just… scattered. There was no one to hold them together.

Eventually, my grandmother started to fall. We hired someone to help, but that generation, they don’t accept help. I think she made it to a hundred, or something close to it. But I’ve never, and I mean never, had someone look at me with that much love. Even in the old folks’ home, she’d be in her wheelchair, and she’d grab my arm, pull me down to her level, and she’d give me that look. A look that would make a man want to kill for her. A look that would make you want to burn the whole goddamn world down, just to make her happy.

“Get me out of here,” she’d whisper. “Take me outside, Jimmy.” But she didn’t have a house to go to anymore.

I think of the hogwash of having guardian angels. Maybe they’re not some clean, winged thing from a painting. Maybe they’re just an old woman with a pot of beans who saves your goddamn life without you even knowing it. I remember being in the Navy, on a payphone in San Diego, after hearing she’d been sick. I remember getting off that phone and just standing there, crying, already trying to think of the words for her eulogy.

I don’t have a poem for her. I don’t have anything pretty to say. I just know that she was the most incredible person I’ve ever known.

Or maybe it was all just because of the beans. Because her beans, they were absolutely, illegally, and divinely delicious.