I used to date my kids.

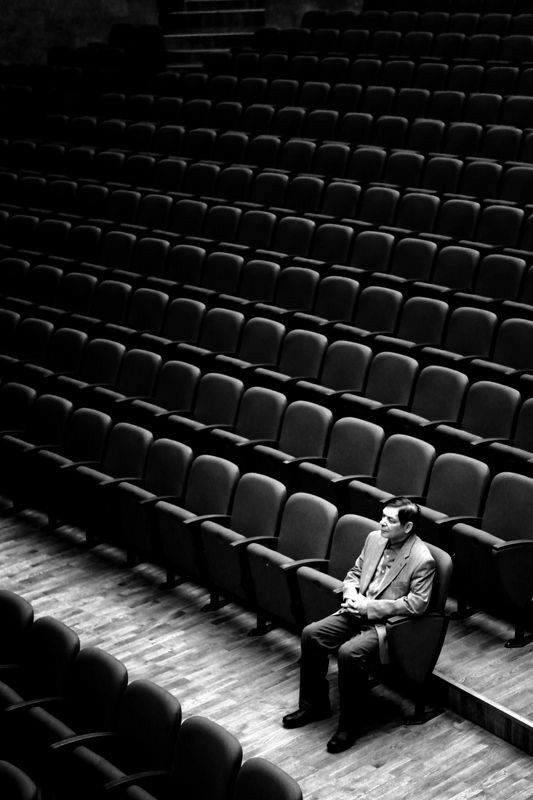

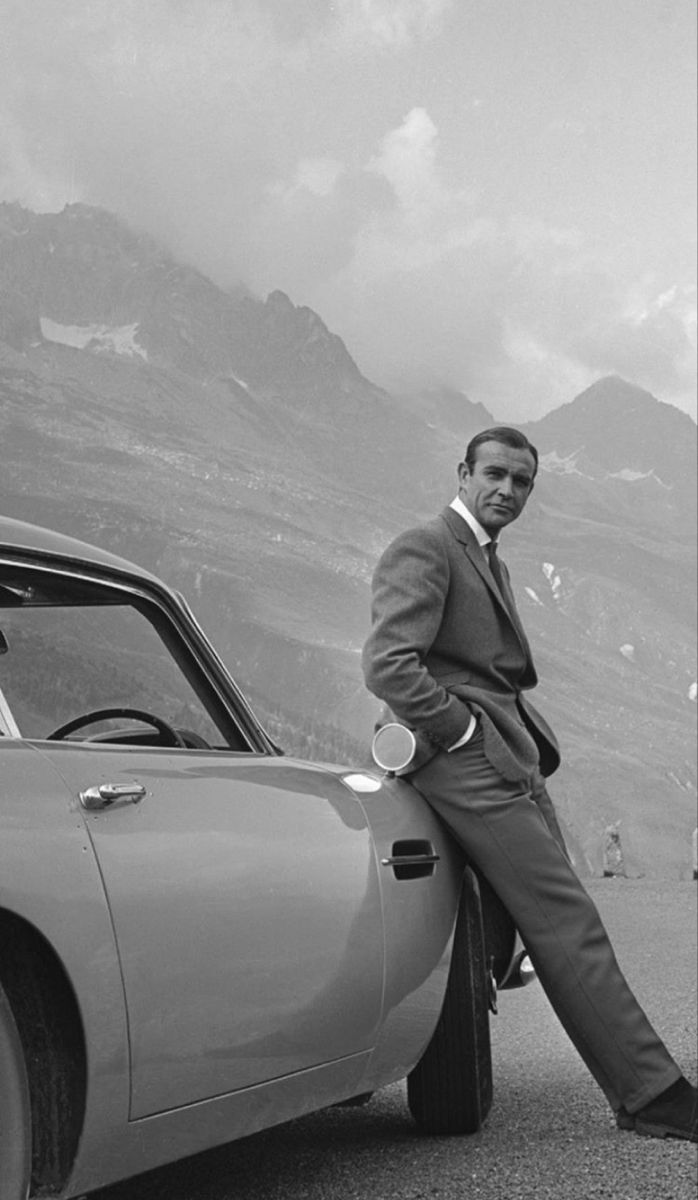

Let’s just start there. Let that sentence hang in the air for a minute, in all its pathetic, beautiful, and completely honest glory. I didn’t see it like that at the time, of course. I thought it was special. A father, spending time with his children. But looking back now, from this quiet, dusty shithole at the end of the world, I see it for what it was.

It was a man, trying to build a little life raft for his kids, while the whole goddamn ship of his life was sinking, slowly and quietly, into the cold, dark water.

Sundays were for my daughters. We’d go to the brewery, and I’d teach them how to order their own food, how to look a waitress in the eye and speak like they belonged in the world. They were great at it. And after, we’d go to the movies across the street, and they’d get all excited, like it was a surprise, like this little, fragile routine of ours was the most normal thing in the world.

Fridays were for my son. Chowder night. We’d go to the brewery, or to Brother John’s, and he’d order for us, a little man with a big, serious voice. “We’ll have the chowder,” he’d tell the waitress, “with everything.” And I’d lean in from the backdrop, the quiet, invisible director of this little play, and I’d whisper, “More cream than meat,” and she’d understand. And the bowls would come out, and my son, he’d be so goddamn proud of himself, sucking down the juice, leaving the meat behind, a perfect, beautiful, and completely honest little boy.

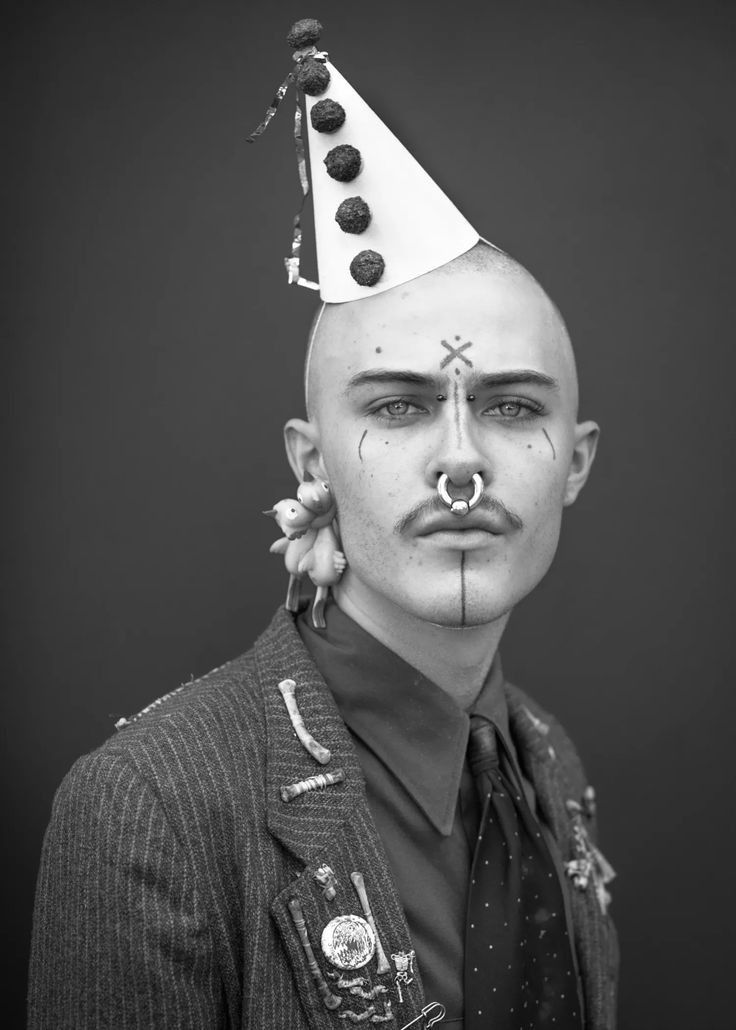

I remember one time, at McGrath’s, he ordered for both of us. The waiter, some good old bastard with a sense of humor, he played along. “Yes, sir,” he’d say. “And my father will have some tobacco and a little bit of butter, please,” my son would add, getting the words a little mixed up. The waiter loved it. When he walked away, my son looked at me, his eyes all bright and clear. “Dad,” he said, “if you’re the king at Amalia’s, then that makes me the prince. And I think we should hire that guy. He’s a good waiter.”

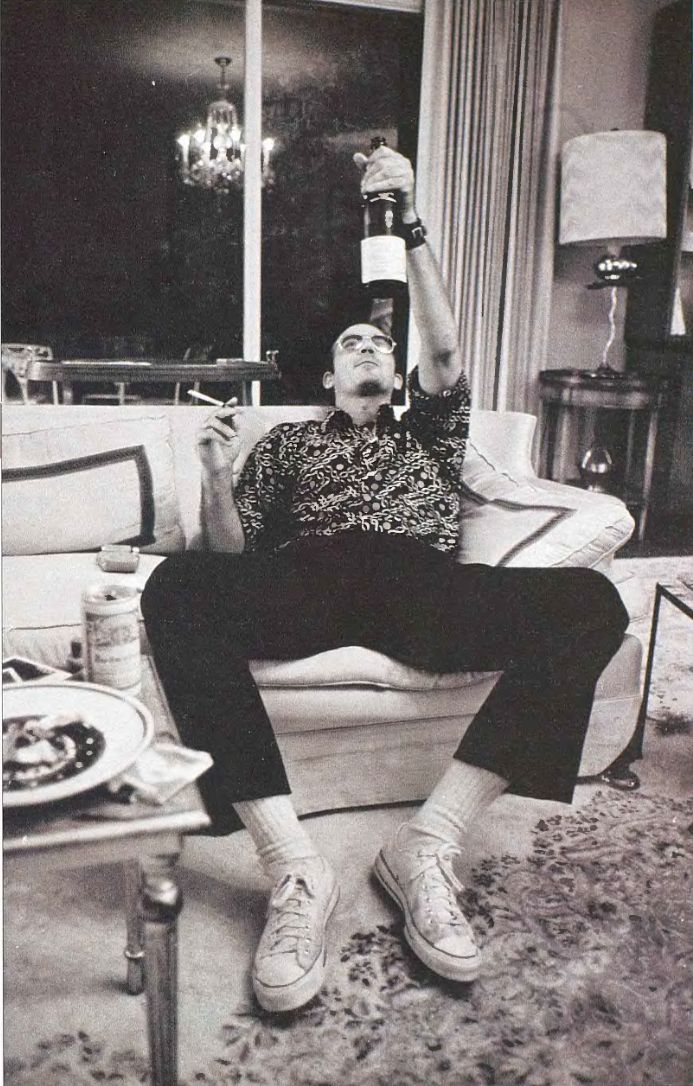

Christ. It makes me laugh, even now. A quiet, ugly, and beautiful little gut-shot laugh. Because that’s the real tragedy, isn’t it? The divorce, it didn’t just break a house; it broke a prince. It disconnected us in a way that’s hard to explain. He’s in his twenties now, and he’s got some of my attributes, but I know, deep down, that more time with me would have been better for him than the time he spent with his mother. But that’s his war to fight now. Not mine.

The best dates were with my girls, at the coast. I’d rent a room at the Whaler, right on the oceanfront, and we’d go to watch the storms roll in. The hotel had these big, ugly floodlights that would shine out on the water, and you could watch the waves, these big, black, angry monsters, coming right at you, a ninety-degree wall of beautiful, ugly, and completely honest violence. I’d make the kids go out on the balcony, and one time, they made a run for the ocean, and the wind, it was a goddamn hurricane, it just picked them up and threw them back, drenched and red and looking like a couple of beautiful, drowned rats.

We’d go back inside, and I’d order a pizza and a couple of two-liters of Diet Coke, and we’d just sit there, in the warm, dry room, watching the storm, watching some stupid movie on the television. And in the morning, we’d walk the beach, looking for treasures in the tide pools.

I don’t know if they remember those moments. But I sure as hell do.

Because looking back now, I see it all clearly. Those weekends, those Fridays and Saturdays and Sundays, we weren’t a family. We were a conspiracy. A little band of refugees, huddled together in the dark, pretending the world wasn’t ending. Their mother, she was at home, a quiet, simmering ghost in a house that was already a tomb. We don’t know what she was doing. But we knew she wasn’t with us. And that was the whole point.

But you want a better conclusion. You want to know what it all means, this beautiful, ugly, and completely pathetic little story.

It’s this.

Those moments, those stolen weekends, those quiet, desperate little dates with my own children… they weren’t the illusion. They were the only real goddamn thing in a world of lies.

The marriage was a lie. The house was a lie. The whole goddamn, respectable, and completely soul-crushing life I had built for myself, that was the lie.

But a little boy, ordering chowder for his father like he’s the king of the world? A couple of little girls, laughing like hyenas as they’re being sandblasted by a hurricane on the Oregon coast?

That was real.

That was the truth.

And in a life that has been full of a lot of ugly, a lot of pain, and a whole lot of bullshit, those quiet, beautiful, and completely honest little moments… they’re the only thing I’ve managed to build that was worth a damn.

They’re the only part of the whole goddamn, fucked-up project that wasn’t a complete and utter waste of time.