The past is a funny goddamn thing. It’s a drunk, stumbling around in a dark room, knocking shit over. The details get lost, the sharp edges get worn down, but the smell of the place, the feel of the cheap carpet under your feet… that stays with you. My past, the real one, the one that put the first few cracks in the foundation, it lives in a town called Whittier, California. 9914 Ahmann Avenue. Right across the street from Gunn Park.

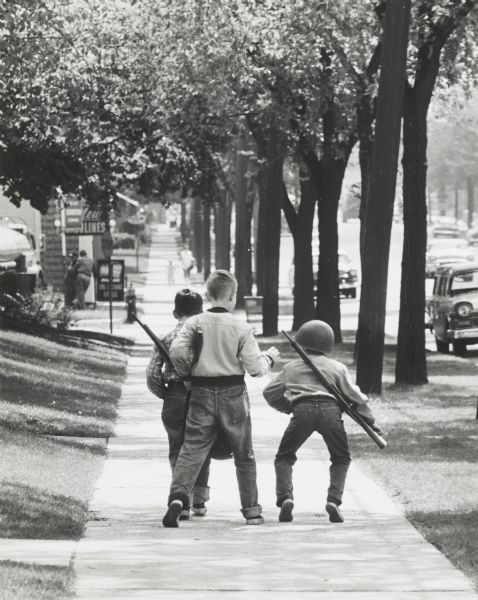

From the outside, it was the whole goddamn American dream, the kind they sell you in the movies. A quiet neighborhood where you knew all the other kids, where the adults would wave at you from their porches as they watered their perfect, green lawns. We were a tribe of little savages, running from one end of the street to the other, masters of a small, green, and completely meaningless kingdom. The fences weren’t chain-link yet; the world hadn’t gotten that ugly.

But inside the houses, inside the heads of the adults who were supposed to be running the show, the rot had already set in.

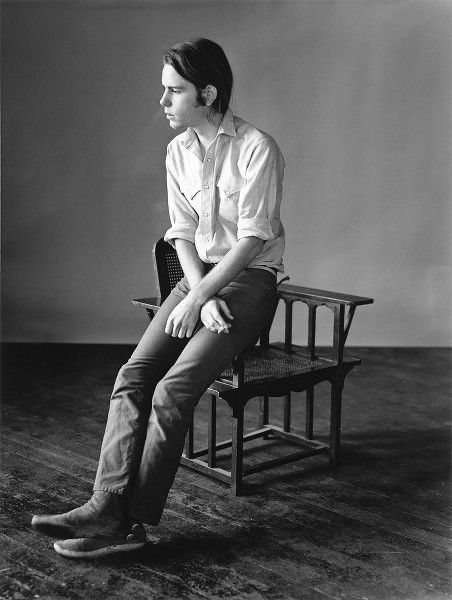

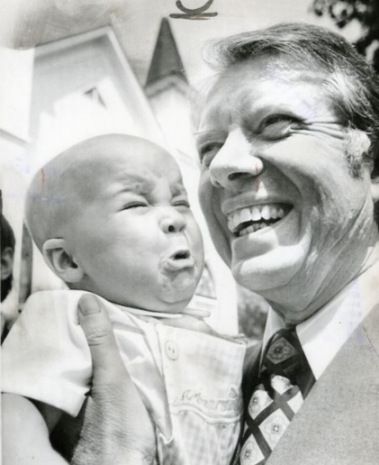

It starts in flashes, like a cheap camera with a dying bulb. Kindergarten at Mulberry Elementary. Riding those little stainless-steel tricycles around the playground, a beautiful, simple machine in a world that was still, for the most part, beautiful and simple. First grade, a tall sonofabitch of a teacher who drove a Stingray Corvette and tried to teach me about cats and hats. He was a good man, I think. He made the words seem like a game worth playing. I remember a Christmas musical, me in a white turtleneck and a red jacket, my skin pale, my eyes a blue that hadn’t seen enough of the world yet to turn to gray. An innocent. A perfect, little, rosy-lipped lamb, waiting for the slaughter.

And then came third grade. And Mrs. Ying. A small, quiet, and completely joyless little Asian woman who looked at the world like it had personally offended her. And that was the year the whole goddamn circus came crashing down.

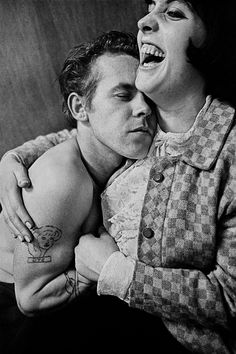

The divorce. My father, that quiet, respectable ghost, he found an old high school flame, a woman named Barbara, and he just… vanished. Into the hills. My mother, left behind with two kids and a house full of cheap furniture, she went on a goddamn rampage. The whole beautiful, phony facade of a family she’d built, it wasn’t needed anymore, so she just let it burn.

I’d sit at my little desk in Mrs. Ying’s classroom, and I’d create my own wars. We had these Styrofoam egg holders for our pencils, and I’d turn mine into a battleship. I’d take my pencil, and I’d poke holes in it, again and again, the graphite leaving little black smudges around the wounds, perfect, beautiful little bullet holes. I was a quiet, sad, and completely absorbed little god of my own private apocalypse. I spent most of third grade standing outside the classroom door. I remember that was the year the lunchboxes stopped mattering. The Million Dollar Man thermos, the Scooby-Doo sandwich holder… those were the artifacts of a different, healthier civilization, a world where a mother still made you a goddamn lunch.

Fifth grade, I just gave up. I’d get a big sheet of paper, the size of my desk, and I’d just draw. For hours. War. Tanks, explosions, command centers, planes dropping bombs. A beautiful, ugly, and completely honest map of the inside of my own goddamn head. And they just let me do it. The teachers, the whole goddamn system, they looked at this quiet, little, shell-shocked kid, drawing his own private Vietnam, and they just… let him. Like I was some kind of special, artistic retard. I remember the principal, talking to someone behind my back, using the word “abused.” But nobody ever called the cops. Nobody ever did a goddamn thing. They just sent me back to the lion’s den every afternoon.

The adults, my own family, they’d reach out to touch me, and I’d flinch. You could see it in my eyes. The trauma. The darkness. A quiet, ugly, and completely visible wound. And not one of them, not a single goddamn one of those brave, respectable, and completely castrated adults, had the guts to pull me out of the fire.

And a boy, a boy has to do something with all that fire.

When my mom would go out to the bars, I’d take a can of her hairspray and a lighter, and I’d go hunting. I’d kick the grass by the sidewalk, and these huge, ugly cockroaches would come skittering out. And as they ran, I’d give them a good, long blast of Aqua Net, a beautiful, sticky trail of accelerant, and then I’d light the end of it. The blue flame would race down the line and poof, the poor bastard would be a tiny, screaming, and completely beautiful little funeral pyre. That was my entertainment.

We were boys. Not bad boys, not yet. Just… boys. Some of us had fathers, some of us were just as lost as I was. But the testosterone, that beautiful, stupid, and completely honest poison, it was starting to cook in our blood. We took to Mulberry Road. We’d steal lemons from some poor bastard’s tree, big, hard, green ones, and we’d hide in the bushes. A car would come screaming down the road, doing fifty, and we’d let them fly. The beautiful, satisfying thump of a lemon hitting a quarter panel at high speed. Then the screech of the tires, the angry red of the brake lights. We’d be gone, of course. Scattered into the suburban jungle, hiding in the bushes, our hearts pounding, watching some pissed-off sonofabitch get out of his car and scream at the empty street, at the universe, at the quiet, invisible ghosts who had just dented his goddamn ride. It was a beautiful thing.

Then came middle school. Hillview. A two-mile, uphill walk to a shithole on a hill. I hated it. At the end of the year, they told me I had to repeat the seventh grade. Was I a retard? Maybe. I couldn’t read, not really. Couldn’t write. Math was a goddamn foreign language. I remember the principal, a real prick, he looked at a paper I’d written. “Write ‘knew’,” he said. So I wrote “new.” And he just snapped. “No, knew something,” he said, and he looked at me like I was a piece of shit he’d just scraped off his shoe.

My organic father, the runner, he reappeared around then. He looked at my grades and decided something was wrong. So, like the asshole he was, he arranged for a solution. A school bus. A special school bus. The short bus. My eighth-grade year, I rode to school with the droolers and the twitchers, the whole goddamn beautiful, tragic, and completely insane menagerie. I’d sit next to a kid in a wheelchair who had uncontrollable drool, the whole bus smelling of piss and quiet desperation. It was horrible. And it was hilarious.

High school was Cal High, right across the street from Hillview, but it was a different world. A different country. By then, the neighborhood had changed. The whites had run for the hills. Now it was all cholos, in their pressed khakis and their tank tops, the women with their makeup caked on like beautiful, tragic war paint. The fences were going up. The security guards were showing up. The innocence was gone. I was one of the few white boys left. A ghost in their world.

I lasted three months. Then I divorced my mother and ran. A quiet, final, and completely necessary escape. I transferred to another school, in another town. I left Whittier behind.

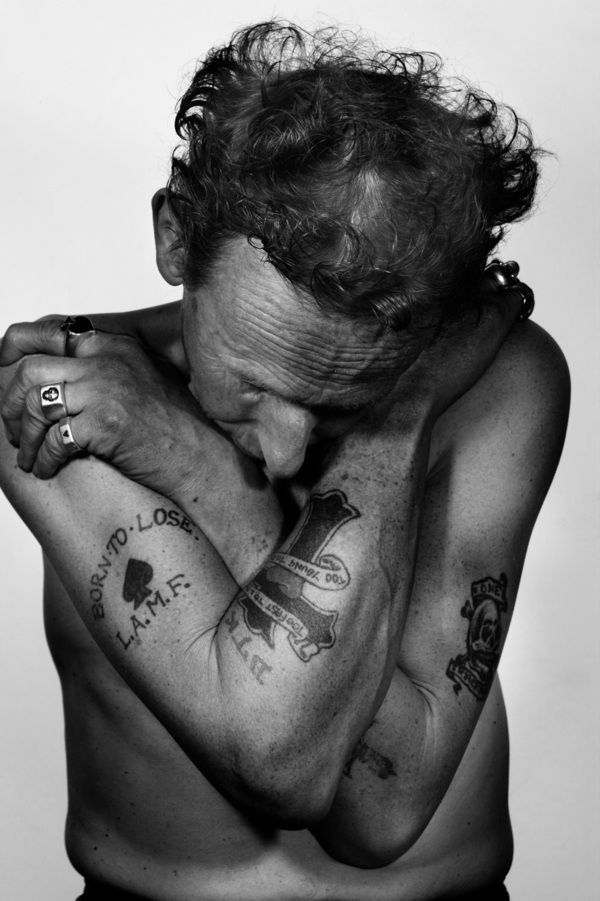

But you don’t really leave a place like that, do you? It stays with you. A quiet, ugly, and beautiful scar. A reminder of the boy you were, and the man you had to become to survive him. I’m fifty-six years old now, and I still can’t do a goddamn fraction. I don’t have a diploma. I don’t have a pedigree.

And when I hear some soft, comfortable sonofabitch complaining that they couldn’t make it because their school wasn’t good enough, I just have to laugh. A real, ugly, gut-shot laugh.

You think school is about learning? Christ. You poor, dumb bastard. School isn’t about learning fractions. It’s about learning how to survive the goddamn fire. It’s about learning the rules, and then figuring out how to break them without getting caught. It’s about learning how to take a punch in the gut in the locker room and come back the next day. It’s about learning how to crawl out of whatever shithole you were born into, so you can go out there and build your own.

That’s the real education.

And it’s a beautiful, ugly, and completely honest inheritance.