A word, my children, on the grand performance of fatherhood.

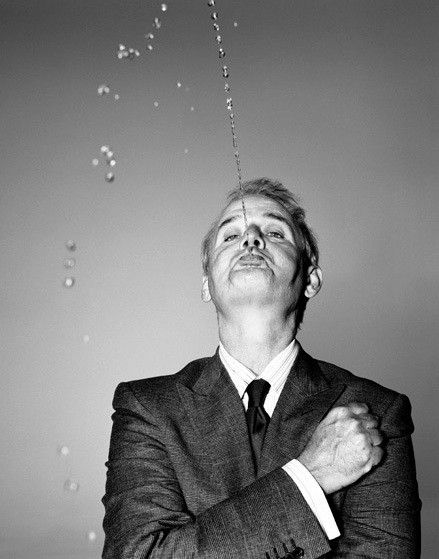

There is a peculiar, well-rehearsed theater to our partings, is there not? At the airport gate, I am the consummate stoic—all pad-hugs and easy smiles. I play it cool, you see. I must. The last thing a father wishes to bequeath his children is the heavy residue of his own heart, to have his love mistaken for the greasy thumbprint of manipulation. And so, I wave, I turn, and I walk away, a man of profound composure.

But then, the curtain falls. The performance ends.

The moment I am alone in the sterile silence of my truck, the facade cracks. It is a ritual, as predictable as the tides and just as salt-filled. The tears are held back, yes, but only until the first freeway on-ramp. I swear to God, for each of you, I have had to pull the vehicle to the side of the road, a blubbering, heaving mess, utterly undone by the sudden, violent grip of an anxiety I cannot name.

The “should-haves” begin their assault, a chorus of phantom regrets.

“I should have said more.”

“I should have held on longer.”

“I should have bought them… everything.”

“I should have done… more.”

Even after our big trip, when we were all together and I felt we had captured lightning in a bottle, the feeling persisted. I did not want to let go of that moment. I did not want to let go of any of you.

It is a baffling affliction for a man like me—a man who has, in all other aspects of life, mastered the art of emotional distance. My job, my own parents, my siblings… I could, in all honesty, probably sever my own pinky finger with a rusty shears and, after a brief shout, feel only a mild remorse for the inconvenience.

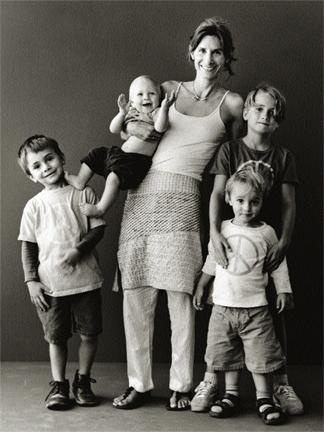

But you… my children… you are an entirely different species of attachment. You possess this unconditional, bizarre, all-powerful hold over me. It is, I suppose, what the poets call f***ing love. A magnificent, terrible, glorious burden. (And thank God none of you ask for much—except, perhaps, for that charming, squattery son of mine, whom I love unconditionally.)

But I digress.

What is the point of this confession? The point is that I am now 57 years old, and I am making plans to depart on a great sabbatical. And with this plan, the old, familiar anxiety builds. I start to analyze it, to trace its origins, and I find the root: I am not going to see my kids. Perhaps for a year.

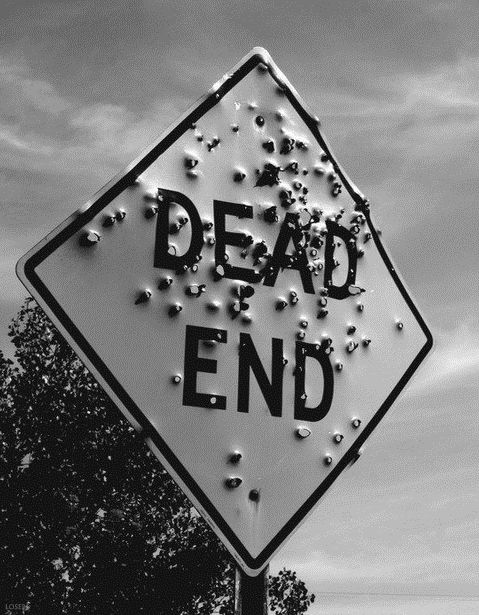

We are scattered across this godforsaken continent, and we may not see each other often, but the option is there. Now, I am removing the option.

And so I feel this theatrical urge to stand up, tap a champagne flute, and deliver a speech for the ages—a great, memorable, fatherly oration before I vanish. “Ladies and Gentlemen…” But what? What could I possibly say that would be enough?

And there is the rub. The grand speech isn’t for you; it’s for me. It’s my own selfish need for closure.

The truth is, I want to be near all of you, to hoard your time and your presence. But I also love you enough to know that you must be yourselves. This is the central, agonizing paradox of parenting. To truly, selflessly love a human being, you must be willing to let them go.

To give up your own desires.

I believe, very much, that if I were a woman—and I am not saying I am, nor that I could be—I would, out of that pure, unconditional love, have my child and give it up to a better home to let it grow, rather than to extinguish it. Or, worse, to keep it and force it to live a selfish, horrible existence like the one I had… to be a pawn, unloved, and radiate that same damage.

Love is giving. I want to give to my kids. I do not want to take.

I know I want to take these feelings with me on my journey. But I also know that I love you so much that I must let you go so you can be yourselves. This is the one sacred rule we always had in raising you: no manipulation.

I am proud that none of you are Mormons. I am proud that none of you are married. I am proud that none of you are following in my path, but are instead blazing your own… albeit with the superior, ass-kicking, name-taking DNA I so graciously provided.

No matter what, even at our lowest points, we are doing great. I look at all of you, and I am overwhelmed with pride at what you choose to do with that DNA. I am just happy that you are happy. I see it in your eyes. And that makes me happy.

So, what’s the point of this whole story?

It’s not easy to let you go. It never has been. But it is the single greatest and most honest act of love I am capable of.

And that, I suppose, will have to be enough.