I wasn’t looking for a miracle when I moved from the Sedona fog down to the Scottsdale heat; I was just looking for a fresh start and a drink that didn’t taste like patchouli. Instead, I ended up at Postino in Tempe, staring across a table at Cheryl—a woman who walked in looking like high-end trouble in heels and walked out proving she was a category-five human disaster.

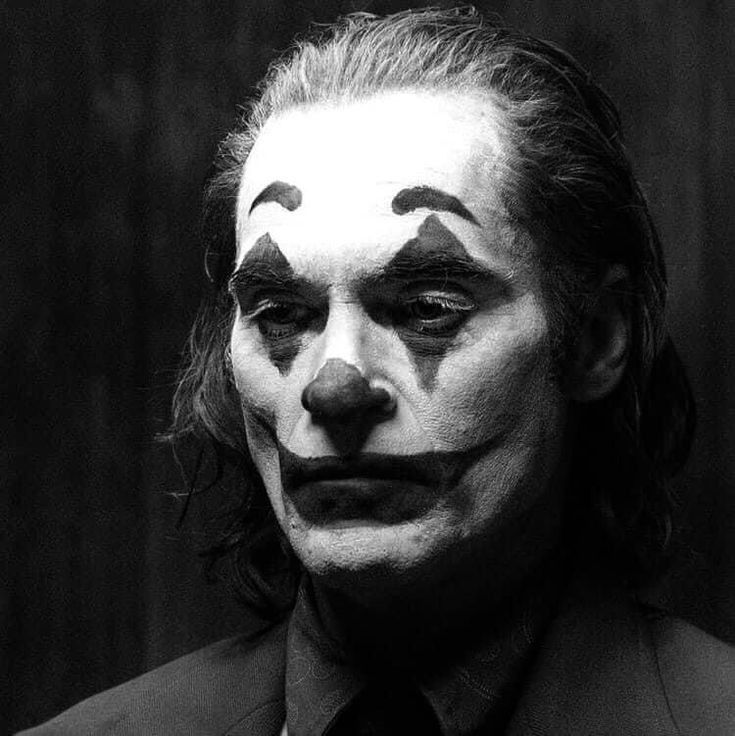

She was stunning, in that specific, manufactured Scottsdale way where the blonde hair is curled by either money or profound misery, and you can never quite tell which. She looked like Cheryl Ladd from Charlie’s Angels if the angels had gone through two vicious divorces and a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation. Age didn’t matter in this town; in Arizona, cosmetics age like military secrets—classified and buried deep.

The conversation started slow, painful, like pulling a confession out of a hostage. But halfway through the second glass of wine, the varnish started to crack. She loosened up. The smile widened, the eyes sharpened, and she grazed my wrist with a hand that felt like it was selecting a piece of prize-winning produce. That’s when I learned the truth: Cheryl wasn’t just beautiful—she was dangerously bored.

She told me she had been the trophy wife, a beautiful, submissive piece of furniture in a house that was too big and too quiet. Her husband sold rugs. Literally. He’d fly overseas, haggle with people who smelled like history, and drag these carpets back to Arizona to sell to rich, culturally confused retirees. He was the provider, the ghost in the machine, gone so often he might as well have been married to the airline.

Their marriage was already a smoking ruin, but they did what people in that tax bracket do: they tried to fix it with real estate. They wanted a bigger house, so they sold the old one before the new one was finished. That meant three months trapped in a luxury apartment with a sixteen-year-old daughter who hated them both with the fire of a thousand suns. The walls were closing in. The hostility was thick enough to chew.

Then came the night.

Cheryl was in the bathroom, getting ready for a mandatory date night with the husband. The daughter had a sleepover brewing. Right as they were heading out the door, Cheryl turned around to give the kid a quick, motherly reminder about the rules.

The daughter looked her dead in the eye and spit out a venomous, perfectly enunciated, “Fuck you.”

And Cheryl—sweet, classy, wine-sipping Cheryl—snapped. The veneer vanished. She lunged across the room, grabbed the girl by the throat, slammed her against the wall, and delivered the line that should have been in a movie: “Don’t you ever talk to me like that again, after everything we do for you.”

The husband, the quiet provider, said nothing. The daughter nodded, terrified. They went to dinner, drank expensive wine, and giggled like they were in a goddamn commercial for the perfect life.

But when they got back, the illusion shattered. There were two police cars waiting. The daughter, that smart, honest, and completely terrifying little bastard, had called the cops.

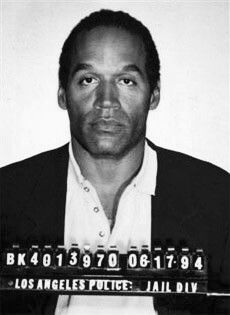

A huge black officer was sitting in their living room like he owned a timeshare in their trauma. “Ma’am,” he asked, calm as a heart attack, “did you put your hands on your daughter?”

Cheryl, being the honest idiot she is, blinked her big doe eyes and said, “Well… I grabbed under her jaw… because of what she said.”

Click. Cuffs.

The next morning, her mugshot was in the Chicago Tribune—apparently, slow news day or just a love for the ironic headline: “Trophy Wife Arrested for Child Abuse.” Name. Face. Full humiliation package. Reputation vaporized. The life she built was destroyed by her own goddamn temper in under ten seconds.

That was the first apocalypse. The second one was biblical.

Despite the arrest, despite the ruin, Cheryl and the rug salesman built the new house anyway. Eight thousand square feet of emptiness, featuring two separate master bedrooms—the architectural equivalent of a silent, polite, and completely dead marriage.

Then, the husband goes on another trip. He comes home, parks his car in the garage, and goes to his room. Nobody sees him. Nobody checks. Why would they? They were roommates who hated each other.

Cheryl goes about her routine: she showers, she lays on her bed, she masturbates, she passes out. The daughter does whatever teenagers do in her wing of the mausoleum.

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Four days straight.

On the fifth day, the daughter finally thinks, Huh, haven’t seen Dad in a bit.

She knocks. No answer. She opens the door.

And there he is.

Swollen, blue, mouth open, eyes bulging like he died mid-sentence and stayed there to prove a point. Four days of decomposition in the Arizona heat will do that to a man. He didn’t just die; he melted into the luxury bedding. The daughter screams, tries CPR on a father who probably crackled like dry leaves when she pressed his chest. Calls 911. Calls her mother. That kind of trauma sticks to your soul like grease.

And here she is, years later, sitting across from me at Postino, telling me this story, confessing her sins to a man who can’t even commit to a gym membership. We saw each other off and on after that—Sedona trips, hotel rooms—quiet little escapes where she could be submissive again, could forget the mugshot and the corpse and the daughter who betrayed her.

She was the last person I saw before I moved to Hawaii. She tried to talk me out of it. “Why are you going? You can stay with me! But how will you support me?”

Support her. After everything we’d done? After all the pretending? It was laughable. I was escaping a cage, and she was asking me to build her a new one.

When I came back from Hawaii, we tried to reconnect. But the fire was gone. She was older, more brittle, hormones shot, taking care of her dying parents, the daughter long gone. She told me sex couldn’t be the priority anymore. “We can’t have sex five times a day, James. I go to church. I have grandkids.”

And the drunk me—God bless him—told her there was no universe where being her caretaker was anything but a downgrade.

But I’ll say this: I’ve met a lot of people. Broken ones. Bitter ones. Dangerous ones. But Cheryl? She was a story wrapped in a woman. The kind that reminds you that other people live truly insane lives too—not always fun, not always sexy, but just crazy enough to make your own madness feel profoundly, beautifully normal.

And those people… those rare, walking disasters… they’re always worth the price of a drink.