We lived in Whittier, right off the 605, a place where the smog was thick enough to chew on, but the dreams were still clean. My father, Jim—the man who stepped up, the man who took the wheel—he knew we were growing. We were getting too big for the little Volkswagen Bug, that cramped little German toaster we started in.

So he upgraded us. He bought a brand new Dodge truck. Brown. With a camper shell on the back.

It wasn’t a luxury suite. It was a metal cave. We’d throw patio mattresses in the back, a couple of buckets filled with Mad magazines and comic books, and that was it. That was our kingdom. The best part was the sliding glass window between the cab and the camper. You could slide it open, knock on the glass, and yell at Dad. Usually to complain that we were beating the shit out of each other, or just to ask, “Are we there yet?” And he’d yell back, “Calm down back there!” It was a beautiful, noisy, moving communication system.

Our destination? El Dorado Park.

It was an oasis. A sprawling, green miracle right next to the freeway. It had nature trails, fishing lakes, and off in the distance, you could hear the pop-pop-pop of the police practice range. It was the perfect soundtrack for a 1970s childhood.

We’d pull up under a massive shade tree. My mom, she was in “domesticated mode” back then, quiet and calm, tending to my little brother Nick, who was just a baby. She stayed near the cab.

But Dad? Dad had work to do.

He’d pull out the bucket. The hose. And the holy grail: the Turtle Wax.

He had so much pride in that truck. He worked his ass off at the Post Office, sorting mail, memorizing zip codes, dealing with the grind, just to buy that piece of machinery. And on Sundays, he worshipped it. He’d apply that wax with a circular motion, his big arms moving in a rhythm, covering the brown paint in a white, hazy dust.

And me? I was set free.

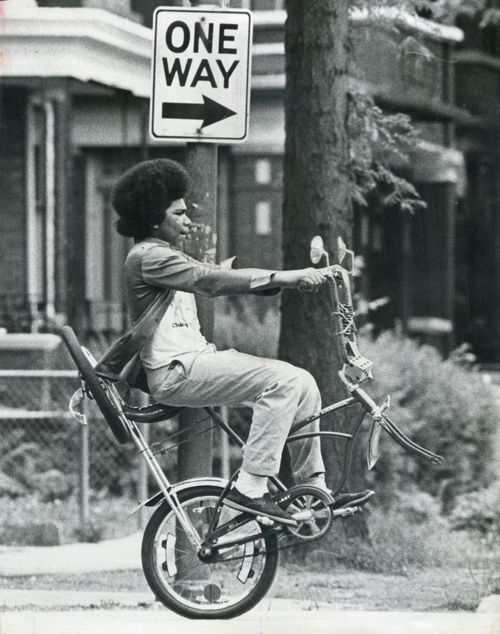

“Go,” he’d say. “Take the bike.”

I’d pull my bike out of the back—banana seat, high handlebars, a death machine on two wheels—and I would vanish.

I’d hit the bike path. I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t have a map. I didn’t have a helmet. I just had speed. Zipping around the curves, the wind in my face, a little explorer in a concrete jungle. I’d stop at a drinking fountain, the water warm and tasting like copper piping. I’d watch a chipmunk, or a squirrel—not the cute Disney kind, but the real, twitchy, city squirrels—scurry up a tree.

I’d make a full loop of the park, miles of freedom, and then I’d circle back to the truck.

Dad would be there. The wax was hazing over. He’d look up, sweat on his forehead, and say, “Go for another round.”

So I would. I’d pedal back out, conquer the park again. By the time I came back the second time, he had the clean rag out. He was polishing. Wiping away the white dust to reveal the shine underneath. The truck looked like a brown mirror.

There were no video games. No iPads. No noise. Just the quiet, rhythmic sound of a man taking care of what he earned, and a boy exploring the world without a leash.

When it was time to go, I’d gather up a couple of acorns, maybe a perfect brown leaf, and stash them in my pocket. Souvenirs from the expedition. I’d hop in the back of the truck, onto the patio mattress, smelling the fresh wax and the exhaust.

It was a good life back then. That’s what a Sunday was supposed to be. Good. Honest. Simple. You didn’t need sex, drugs, or rock and roll. You just needed a dad who gave you a bike and a park, and then stood there, polishing his truck, creating a safe, shiny home base for you to come back to.

I cherish those moments. I really do.

I love that man for making a world where a kid could just… ride.