I’m sitting here, fifty-seven years of mileage on the odometer, packing a bag for a country I’ve never seen, and I’m thinking about a movie.

Most movies are bullshit. They’re cotton candy. They’re two hours of beautiful people pretending to have problems that can be solved with a conversation and a soft piano soundtrack. I don’t watch them. I don’t feel them.

But there is one.

There is one movie that, when I watch it, I have to pour a drink. I have to sit in the dark. And sometimes, when the credits roll, I have to walk outside and stare at the desert just to make sure I’m still breathing.

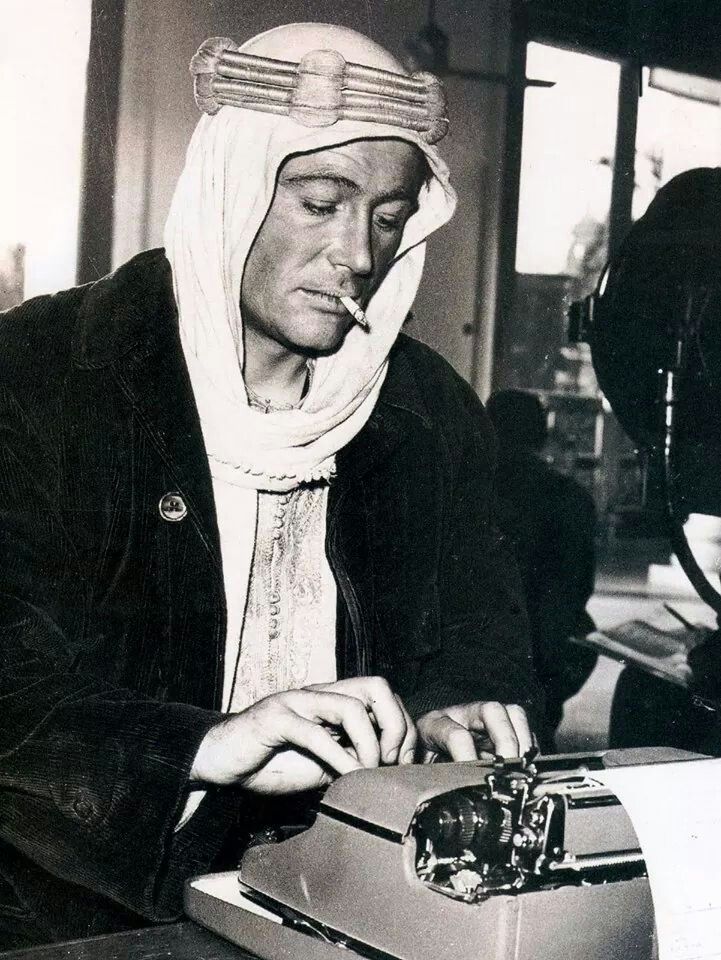

And if you want to know who I am—who I really am, under the Project Manager suit, under the “Good Guy” mask, under the scar tissue of three hundred women and fifty years of chaos—you just have to watch Robert Redford drag a frozen elk through the snow.

The Mountain as a Metaphor for the Exit

The story starts the only way a good story can: with a man turning his back on civilization.

Jeremiah isn’t running from the law. He isn’t running from a woman (though, God knows, that’s usually part of it). He’s just… done. He’s done with the towns. He’s done with the rules. He’s done with the “flatland” mentality.

He buys a Hawken gun. He buys a horse. And he rides up into the Rockies to become a mountain man.

That’s me. Right now.

I’m trading the horse for a plane ticket to Vietnam. I’m trading the Hawken for a laptop and a passive income stream. But the spirit? It’s the exact same goddamn thing. I am looking at the “town”—at Tucson, at the corporate ladder, at the dating apps full of broken people—and I am saying, “I’ve been to a town, Del Gue. It ain’t nothing but noise.”

I want the wind. I want the cold. I want the silence that is so loud it rings in your ears.

The Burden of the Unwanted Family

But here is where the movie gets me. Here is where it sticks the knife in and twists.

Jeremiah wants to be alone. He craves it. He builds his cabin. He learns to hunt. He finds his peace.

And then? The world dumps a family on him.

He doesn’t ask for it. He finds a mute kid whose family has been slaughtered. He gets saddled with a crazy woman as a “gift” from a Chief. Suddenly, the man who wanted nothing but solitude is playing father and husband to a group of broken castaways he didn’t choose.

And I watch that, and I see my life.

I see the women I saved. I see the low-hanging fruit I picked up because they were there, because they needed me. I see the “social work” I did for twenty years, building houses for people who couldn’t pay the rent, fixing lives that were shattered before I got there.

Jeremiah tries. He really does. He builds them a home. He protects them. He shaves his beard. He becomes the “Good Provider.” He plays the role of the Stepfather, the husband, the man who sacrifices his own nature to keep the fire burning for someone else.

And what happens?

The Crows come down and slaughter them.

He comes back to the cabin, and it’s all gone. The family. The life. The illusion of safety.

And that scene… where he burns the cabin down? Where he walks away from the smoking ruin of the domestic life he never really wanted but tried so hard to maintain?

That is my divorce. That is me leaving the Navy. That is me walking out of the big house in Bend, Oregon. That is the “Apocalypse” I’ve written about a dozen times.

It’s the realization that you can build the perfect cage, you can be the perfect zookeeper, but eventually, the wolves are going to come. And all you’ll have left is the ash.

The Feral King Returns

After the slaughter, Jeremiah doesn’t go back to town. He doesn’t go to therapy.

He goes to war.

He hunts the Crows. One by one. He becomes a legend, not because he’s a hero, but because he is a force of nature. He stops talking. He stops trying to be civilized. He becomes the “Feral King” of the mountains.

I feel that. I feel that in my bones. When I’m cornered, when the system tries to crush me, when the women try to tame me… I don’t negotiate. I hunt. I survive. I turn into the thing that scares them.

The Nod

But the part that breaks me—the part that makes me walk away from the TV—is the end.

Jeremiah is old now. He’s tired. He’s scarred. He’s survived the winter, the Indians, the hunger, the loss.

And he sees the Crow Chief. The man who killed his family. The enemy.

They are far apart, separated by a field of snow.

Jeremiah reaches for his gun. The Chief raises his hand.

It’s not a threat. It’s a salute.

It’s the Nod.

And Jeremiah pauses. He looks at this man, this enemy, this fellow survivor in a brutal, indifferent world. And he nods back.

That’s it. That’s the whole goddamn meaning of life right there.

It’s not about winning. It’s not about “happiness.” It’s not about the money or the girl or the house.

It’s about surviving the mountain.

It’s about getting to the end of the movie, covered in scars, freezing cold, alone, and looking at the universe—that old, drunk, sadistic bastard—and nodding.

“I see you. You didn’t kill me. I’m still here.”

That’s why I’m going to Vietnam. I’m looking for my mountain. I’m looking for the place where I can finally stop fighting the town and just exist in the wild.

I want to earn that nod.

And maybe, just maybe, if I’m lucky… I’ll find a place where the wind blows the names of the dead away, and a man can finally get some sleep.

Watch your top knot.