When I left that house at thirteen, I didn’t just walk out the door; I defected. I moved in with my “Archaic Dad,” a man who was as steady and boring as a concrete pylon, which was exactly what I needed. But in doing so, I severed the line. I cut the cord.

I didn’t see the “Organic Whack Jobs”—my biological family—for a long time.

It wasn’t until later, when I was living with my grandmother, that the reunion happened. I reconnected with Nick. And on the weekends, I saw Ryan.

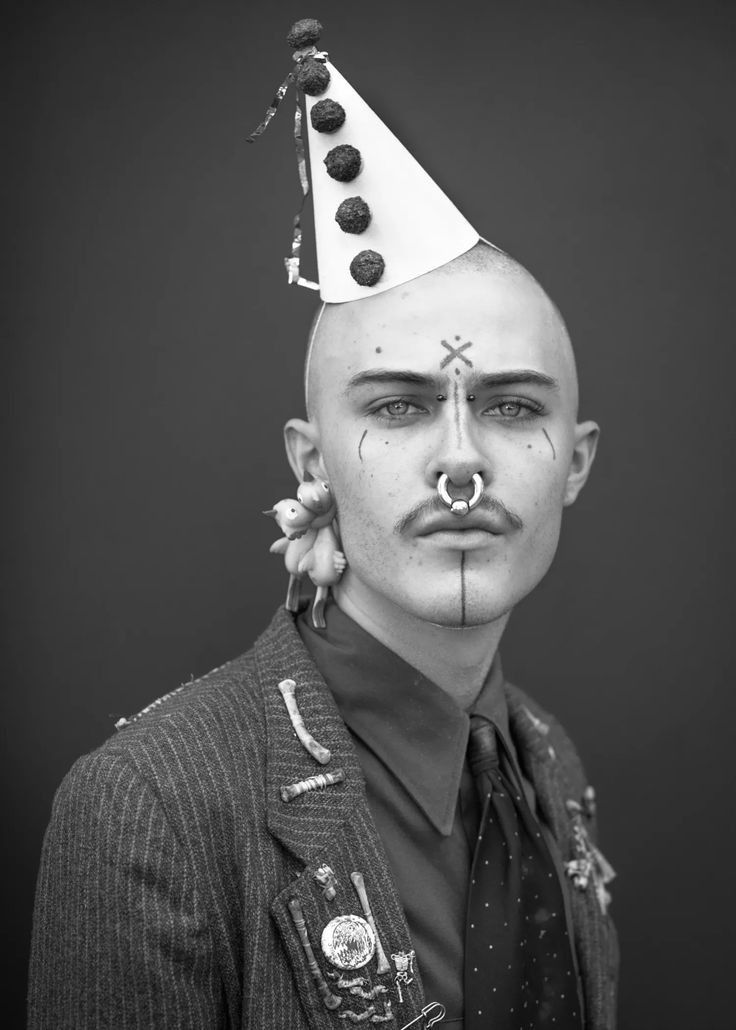

Ryan had grown up in the dark. He was angry. He was jagged. But when the three of us got together? My God, it was a comedy club in hell. They say comedy is the disguise of a hurt soul; well, we were masters of the craft. We laughed until we couldn’t breathe. We cracked jokes to cover the sound of the breaking glass in our heads. I realized then that all three of us shared a specific, tragic gift: We could not answer a straight question. We deflected. We spun. We turned trauma into a punchline because if we didn’t laugh, we would have to burn the building down.

The Return to the Shithole

I remember the day I had to go back. I had stooped low enough to ask my mother for a ride in her little green Volkswagen. She drove me back to the house I had escaped.

I walked in, and the smell hit me like a physical blow.

It wasn’t just “dirty.” It was the smell of a storage unit that had fermented in the heat. It was the thick, cloying scent of stagnation and rot. Nothing had changed in three years. No fresh paint. No new carpet. The walls were yellowing with age and smoke. The screens were gone from the windows. The doors looked like they had been kicked in and poorly repaired—a geography of violence mapped out in wood splinters.

And the filth. Jesus.

My mother’s personal hygiene had devolved into something primal. She didn’t use the trash can. You’d find her “period pads”—disgusting, bloody relics—shoved behind the couch, or under the cushion, or just laying out in the open like dead rats. The air was thick with the smell of dried blood, dog shit, and apathy.

I walked into the spare bathroom. There was a lump of shit in the toilet that had been there so long it had fossilized.

My brother Ryan was still living in this. He was still going to school from this launchpad of squalor. I stayed for two minutes. I physically couldn’t do it. The triggers were too loud. I felt the walls closing in, and I ran.

The Cemetery Logic

But you can’t run from your own brain.

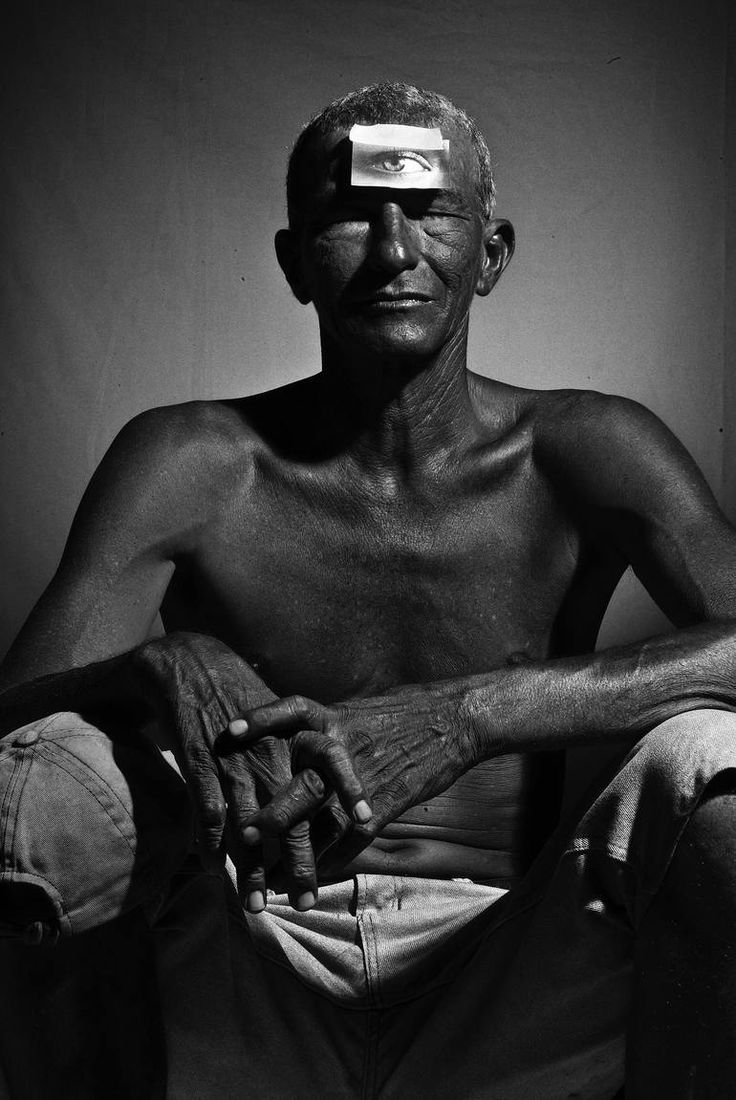

I was fifteen. I was heavy into the psychedelics. I was sitting in Forest Lawn Cemetery—where Karen Carpenter sleeps—trying to listen to Jimi Hendrix and get a psychedelic butterfly to land on my third eye.

But instead of peace, I got The Math Problem.

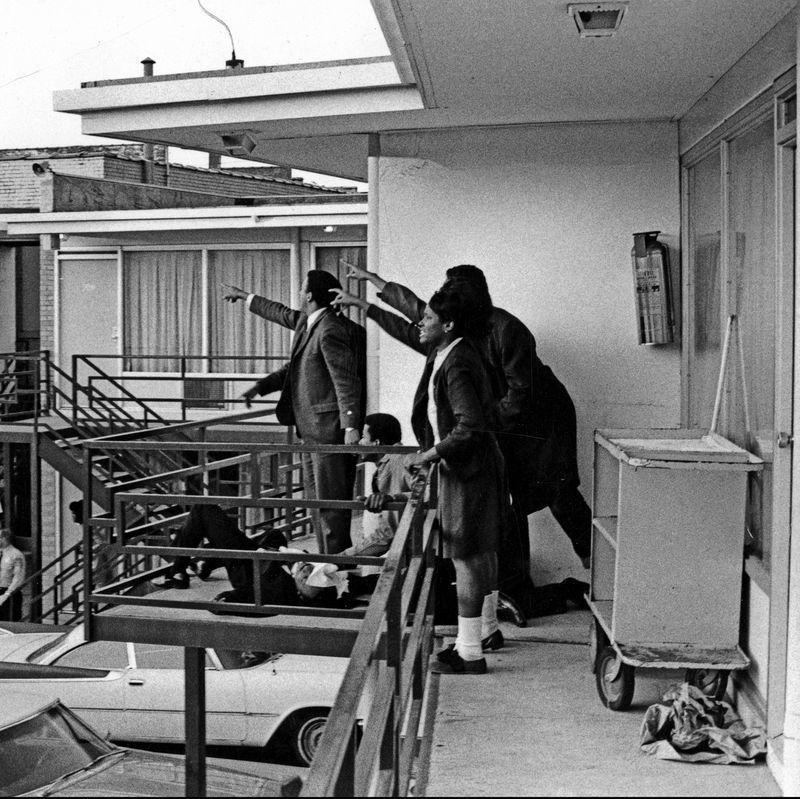

I spent eleven hours in that cemetery, staring at the grass, thinking about Ryan. The acid stripped away the bullshit and left me with the raw, vibrating question: What should I have done?

Should I have stayed? Should I have taken the punches for him? Should I have been the Big Brother at 13 and just absorbed the abuse so he didn’t have to?

I worked the problem like Einstein working on relativity. I played every scenario. I looked at every variable.

And the acid gave me the answer. The only answer.

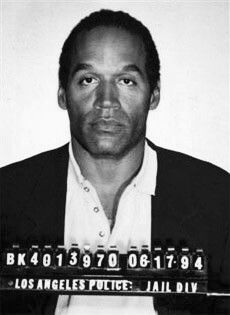

I should have terminated her.

I played it out in my head. It wasn’t a suicidal thought; it was a tactical simulation. I had ten ways to do it, but I narrowed it down to the most efficient one.

The Scenario: She comes home drunk. She passes out. I take the pillowcase off my pillow. I straddle her like a bull rider. I wrap the linen around her neck. I pull back. I use the leverage of my young arms against the dead weight of her drunken neck.

It was so vivid. The acid made it 4K resolution. I could feel the tension in the fabric. I could feel the resistance. I could see the light go out of her eyes.

And the logic was flawless: If I kill the Monster, the hostage goes free. If I had done it sooner, Ryan would have been placed in a home. He would have gotten attention. He would have been saved from the slow-motion car crash of being raised by a feral woman.

The Fork in the Road

But I didn’t do it.

I didn’t kill her. And I didn’t stay.

I took the third option: Abandonment.

I saved myself. And in doing so, I left Ryan to sink or swim in the sewer I had just crawled out of.

That choice created the fork in the road. Ryan went down the path of Anger. He hardened. You can see it in his eyelids today—heavy, distrustful, pissed off at the world. I went down the path of Guilt. I am haunted by the ghost of the murder I didn’t commit and the rescue I didn’t perform.

I fell on the sword of guilt so I wouldn’t have to wield the knife of matricide.

And my brother paid the price.