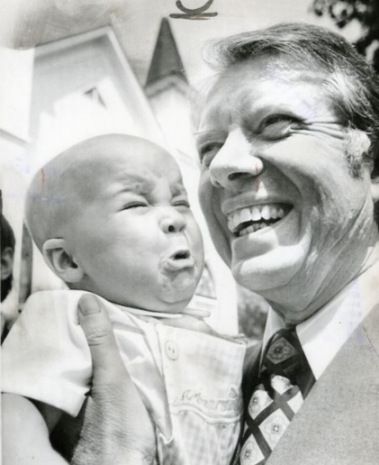

My little brother, Ryan, wasn’t born into a family; he was born into a vacuum. He arrived at a time when nobody had any vacancy in their heart for another mouth to feed, another noise to manage. He was an accessory to my mother’s delusion of “independence,” which in the 1970s meant leaving a baby in a crib for eight hours while she went out to conquer a man’s world with a bra full of ambition and a fridge full of mold.

I was his warden. I wasn’t a brother. I was a feral child tasked with keeping a smaller feral child alive.

He would lay in that crib, steeped in his own filth, screaming for attention that was never coming. And me? I didn’t have sympathy. I had a headache. I’d close the door to muffle the sound. Or, in my darker, more experimental moments, I’d reach into the crib, cover his mouth with my hand, and plug his nose. I’d watch his eyes roll back, watch the panic set in, until he passed out from lack of oxygen. I told myself it was a “magic trick” to make him sleep. It wasn’t. It was a power trip. It was the only control I had in a house where chaos was the landlord.

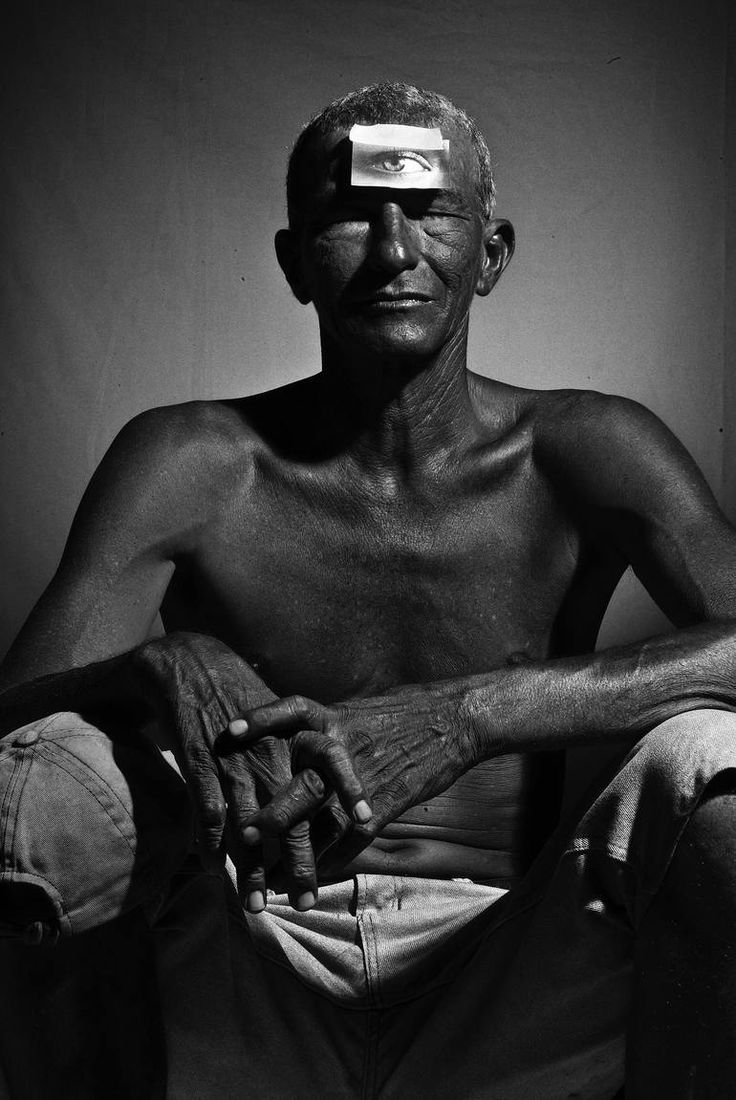

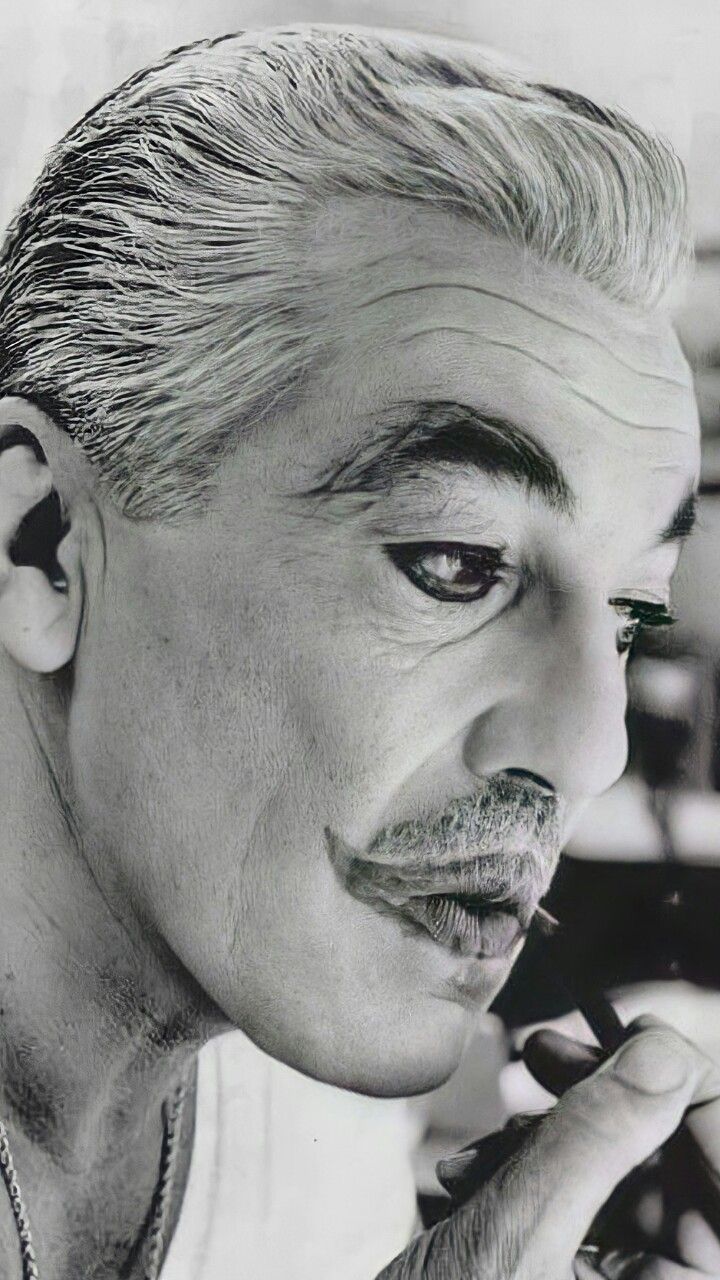

The Frankenstein Skull

Because we neglected him—because we left him in that crib like a carton of expired milk—his head deformed. We didn’t rotate him. So the back of his skull went flat. It pressed against his ears until the skin behind them cracked and bled. We had to lotion him up just to keep his head from splitting open.

And then came the patio incident.

I remember it in slow motion. He was on his tricycle, trying to do a wheelie like the big kids, and he flipped backward. His head didn’t just hit the concrete; it found the one jagged rock on the slab.

Crack.

It sounded like a melon being dropped from a roof. The blood wasn’t a trickle; it was a geyser. I remember the rush to the hospital, the panic, the sheer incompetence of our supervision coming to light. He came back with his head shaved and a line of heavy-duty staples running ten inches up the back of his skull. He looked like a Frankenstein experiment gone wrong. To this day, you can see it—the flat head, the scar, the map of a childhood where safety was a foreign concept.

The Education of the Arsonists

We were animals. We raised ourselves on tuna casserole that was three days old and the adrenaline of doing shit that should have killed us.

We knew the schedule. Mom wouldn’t be home until the bars closed. That was our playtime.

We’d go out into the suburban darkness with her giant, industrial-sized can of hairspray and a Bic lighter. We became gods of fire. We’d find a cockroach scurrying on the sidewalk. Psssshhhht-FWOOM. We’d light the stream. The roach would run, flaming, down the pavement, a tiny torch screaming in silence until it curled up and died. We laughed. We loved it. It was the only warmth we felt all night.

Then there was the garbage man.

My brother was hanging out the window, watching. I had my BB gun. I didn’t hesitate. I aimed right at the tattoo on the man’s bicep and pulled the trigger.

He gasped. He dropped the can. He grabbed his arm and screamed curses that echoed off the houses. I ducked. But Ryan? Ryan just kept his head out the window, watching the pain. He didn’t flinch. He was learning.

The Descent of the Peacock

The abuse rolls downhill. My mother abused us, so we abused anything smaller than us.

She brought home a peacock once. Why? Who knows. It was part of her “exotic” persona. We let it loose in the living room. We chased that bird with racquetball rackets and pillowcases, beating it, terrorizing it, knocking it silly until its feathers were torn out. It eventually died of shock. We killed it with stress. And yeah, we got in trouble, but the lesson was already learned: Power is inflicting pain on something that can’t fight back.

The Headlights in the Driveway

The most terrifying sound in the world was the crunch of tires on gravel after midnight.

When the headlights swept across the living room window, we scattered like roaches. We knew the drill. We had to assess the threat level instantly. Was she “Happy Drunk”—the sloppy, affectionate best friend who wanted to eat cereal at 2:00 AM? Or was she “Monster Drunk”—the woman who hated her life and wanted to break something?

It was usually the Monster.

When the rage started, Ryan would run to my room. He was smart. He used me as a human shield. He’d hide behind me, and I’d take the hits. She didn’t use a belt; she used her hands, her words, and her shoes.

But the worst punishment wasn’t physical. It was the destruction of the Totems.

We had a collection of Hot Wheels. Matchbox cars. We kept them pristine, wrapped in napkins in a little briefcase. They were our only currency, the only things we owned that were beautiful.

When she really wanted to hurt us, she didn’t hit us. She went for the case. She’d stomp on it. She’d kick it across the room. She’d snap the axles and crush the roofs of our cars while we watched. I remember looking at Ryan. He wasn’t crying. He was just… emptying out. He was learning that nothing is safe. Nothing is yours.

The Fight and the Abandonment

I never got to say goodbye to him.

The end was violent. My mother and I got into a fistfight after one of her binges. I was thirteen. She tried to kill me, and for the first time, I hit back. We traded punches to the face. I don’t know who won, but I knew the war was over.

I went to court. I emancipated myself. She signed the papers just to get rid of me.

I remember sitting in a donut shop with my dad afterwards. I was free. I was out. And I looked at him—this archaic, stoic man who knew exactly what was happening in that house—and I asked the question that haunts me to this day.

“Can we get Ryan? Can we bring him too?”

My dad didn’t hesitate. “Hell no.”

His new wife didn’t want me; she certainly didn’t want the flat-headed, feral little brother who looked like a walking tragedy.

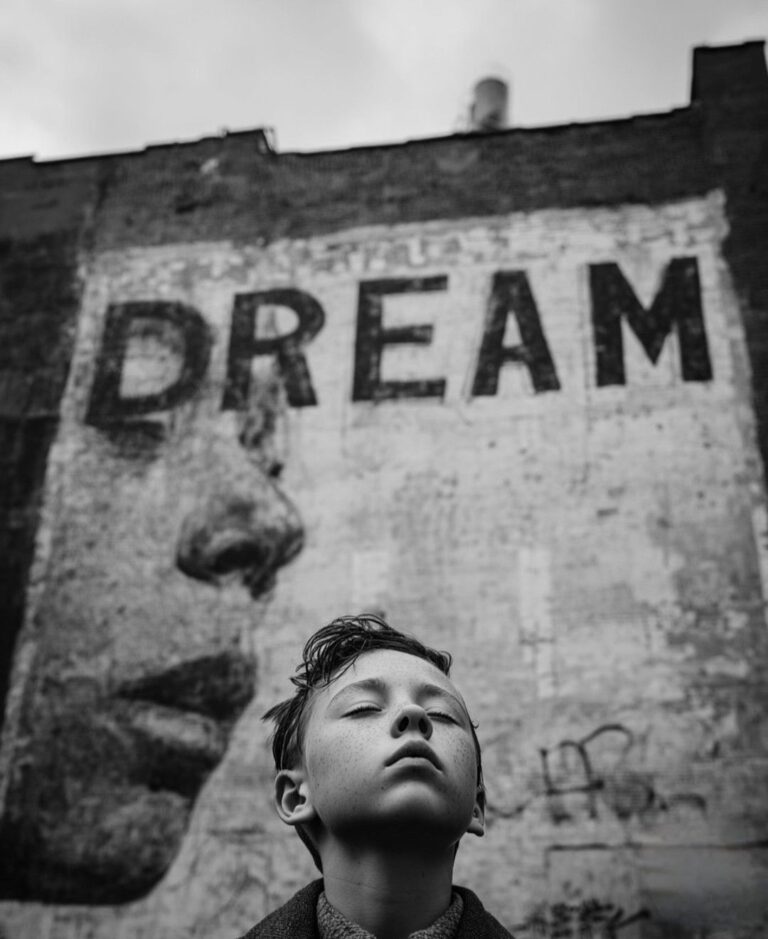

So I left him.

I walked out of that donut shop and started my life. And I left my little brother in that house, with that woman, to face the headlights alone.

I escaped the fire. But I left a hostage behind to burn.