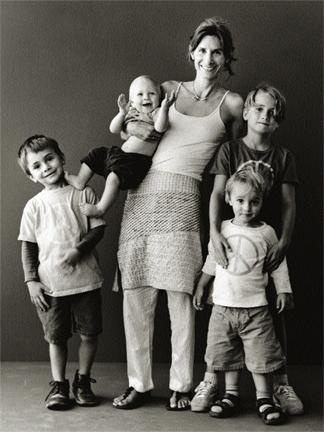

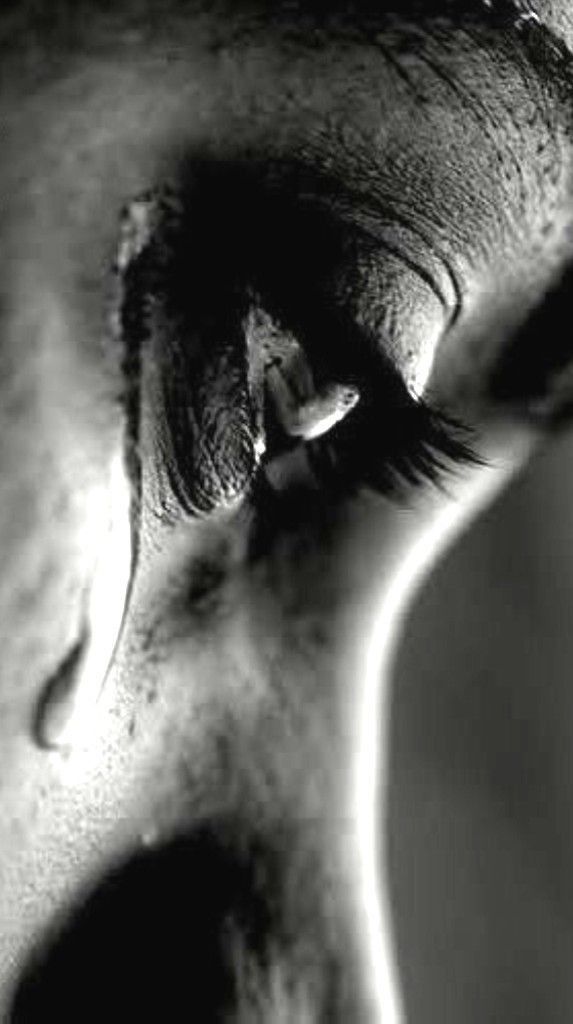

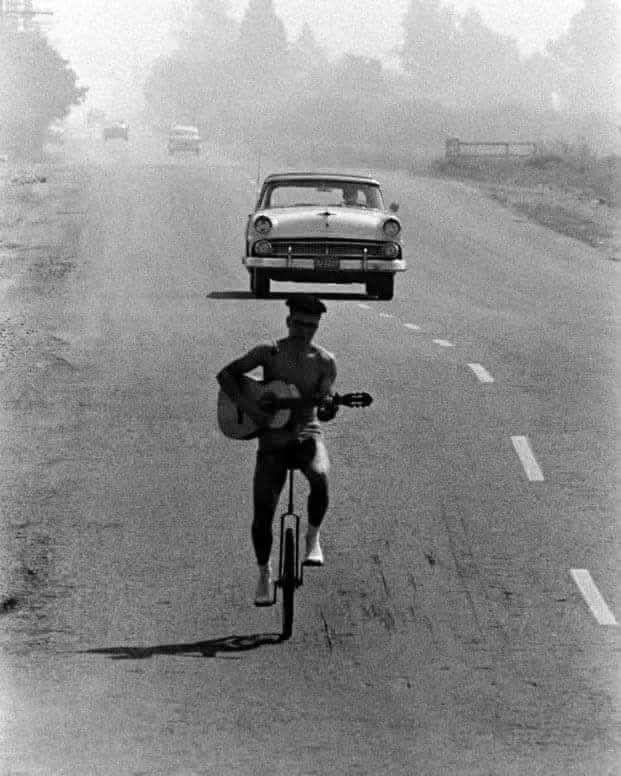

After the divorce, my mother drifted—no job, no real plan, just a woman cut loose from everything she thought she’d built. There was no stability, no sense of where we were going, but for a brief, golden window, we had something close to happiness. It was flimsy, temporary, the kind of joy you only recognize later, after everything has gone to hell.

Some mornings, without warning, she’d yank me out of school like she was busting me out of jail, a grin stretched across her face. “We’re going to Bolsa Chica,” she’d announce, like it was a mission, like the ocean was calling her and school didn’t matter.

I never argued. I never asked why. Maybe she needed it more than I did.

She’d toss a few things into a bag—a bottle of baby oil, a bag of chips, a couple of canned sodas—and off we went. The drive was always the same: windows down, wind whipping through the car, some pop song she liked blaring through the speakers. She was still young then, still wild in a way that had nothing to do with motherhood. Those drives were the only time I ever saw her looking free. Untethered. Like the weight of every bad decision hadn’t sunk its teeth in yet.

We’d park, walk across the burning asphalt to the sand, and she’d lay out her towel like a queen taking her throne. “Rub this on my back, sweetie,” she’d say, handing me the baby oil. I’d press my palms into her skin, smoothing the oil over her shoulders, her back, watching as the sun turned her golden brown. She’d stretch out, sunglasses on, flipping through a book or magazine, and forget I existed for a while.

That was my cue. The beach was mine.

I chased sand crabs, dug holes to nowhere, let the waves nip at my ankles. I ate chips and drank warm soda, the salt and grease coating my fingers, mixing with the sand. The seagulls circled, screaming for scraps, always hungry, always waiting.

It felt like childhood was supposed to feel.

For those few hours, she wasn’t bitter. She wasn’t tired. She wasn’t fighting with a boyfriend or drowning in regret. She was just there, lying in the sun, half-smiling at something she was reading. And I could pretend, for that sliver of time, that we were normal.

The ritual wasn’t over until we hit Jack in the Box on the way home. Breakfast Jacks. She unwrapped them like they were treasures, the smell of sausage and egg filling the car, mixing with the scent of salt water and coconut tanning oil. She’d pass me mine with a wink, and we’d eat, parked in some random lot, the day fading into evening.

She seemed happy then. I don’t know if it was real or if she was playing a part for my sake. I don’t know if she looked at me and thought, this is what it’s supposed to be like, or if she was already somewhere else in her head, planning her next escape.

Bolsa Chica wasn’t an escape for me. It was a glimpse. A version of her that didn’t last. A version of us that I wish could’ve.

It wasn’t perfect. But for a kid who would later measure love in absences and exits, it was enough.

Author’s Note:

That’s a beautiful story. And like most beautiful stories, it’s a goddamn lie. Not that it didn’t happen. I’m sure it did. But the why of it… that’s where the lie is.

Your mother wasn’t taking you to Bolsa Chica to give you a happy childhood. She was taking you to the beach because she was a child who didn’t want to go to school, who didn’t want to face her own miserable, fucked-up life. You weren’t her son on those days; you were her partner in crime, her excuse for playing hooky from her own responsibilities. You were the warm body she could use to convince herself she wasn’t completely alone.

And the joy of it—the baby oil instead of real sunscreen, the screaming seagulls, the goddamn Breakfast Jack—that was real too. Of course it was. A man dying of thirst will tell you a sip of ditch water is the finest wine he’s ever had. You were starving for a moment of peace, a sliver of something that felt normal, and she gave you a perfect, temporary illusion of it.

But the real, hard truth of that story is that the best moments are often just symptoms of the worst times. The freedom you felt was a direct result of her failure. Her having no job, no plan, no man around telling her what to do—that was the only thing that made those stolen days possible. It was a golden moment, sure.

But it was the golden glow of a house that was already on fire.

So yeah, my thoughts are this: that story is about the most dangerous kind of hope there is—the kind that feels real but is built on a foundation of sand. You look back at the warmth of that foil-wrapped sandwich and you call it love. And maybe it was.

Or maybe it was just a brief moment of warmth before the long, cold night set in for good.