I was a haole—white mainlander—trying to manage construction projects on the west side of Oahu. Not just any projects. Big ones. Government jobs, infrastructure—projects that put you in the mix with hard men, Filipino and Hawaiian, most with tribal tattoos curling up their necks and arms thick as palm trunks. They didn’t trust easy, and I didn’t expect them to. For five years, I walked among them like Captain Cook on borrowed time—building friendships where I could, dodging metaphorical spears where I couldn’t. It took time, sweat, and a hell of a lot of restraint to earn even a sliver of that trust. Still, some days, I could feel the heat in their eyes, like they were still sizing me up for the imu pit.

Then came the digester job.

I didn’t ask for it. Some jerk-off kid had been babysitting the project before me—lazy, arrogant, pulling a third of the weight and acting like he’d invented construction management. Geoff, the senior PM / Retired Preadent of the Company and my mentor, had seen enough. One morning, when I was in the main office working out accounting issues, he came storming off the jobsite, barking like a pit bull that’d chewed through its leash.

“You! pointed at me, You need to clean this shit up and get this project, your the digestor man. She’s yours now.”

That was it. No handoff, no sit-down meeting. Just a verbal punch in the gut and a shove into the fire.

I dropped my other jobs, kissed ’em goodbye, and drove out to Waianae full-time. The west side of Oahu—it’s goddamn gorgeous, sure, but don’t let the sunsets fool you. It’s also where the island dumps what it doesn’t want to see. The homeless. The broken. The leftovers. The real Hawaiians, too—the ones who didn’t sell out or get bought out. They hold the line out there. And they know who don’t belong.

A haole like me? I was a walking reminder of everything they’d lost. They didn’t hide it. Hell, they doubled down. Made sure I felt it in the stares, the silence, the slow bleed of trust.

And I loved every goddamn second of it.

The project was a monster—a one-million-gallon digester remodel for the wastewater treatment plant. The existing lid had caved in years back, rotting under the island sun and bureaucratic delay. The plan was to demo it, cut it out in chunks, and prep for a brand-new prefabricated steel lid. That lid had been built up in Washington state, then shipped across the Pacific by barge like some oversized, rust-covered casket. Our job was to weld the pieces together on-site and crane that beast into place without killing anyone—or ourselves.

Every piece of this project had weight—and not just in steel. I’m talking about the kind of weight you feel in your chest before you even set foot on the dirt.

Political weight. Too many white hats slapping each other’s backs while the real work happened in the sun.

Cultural weight.

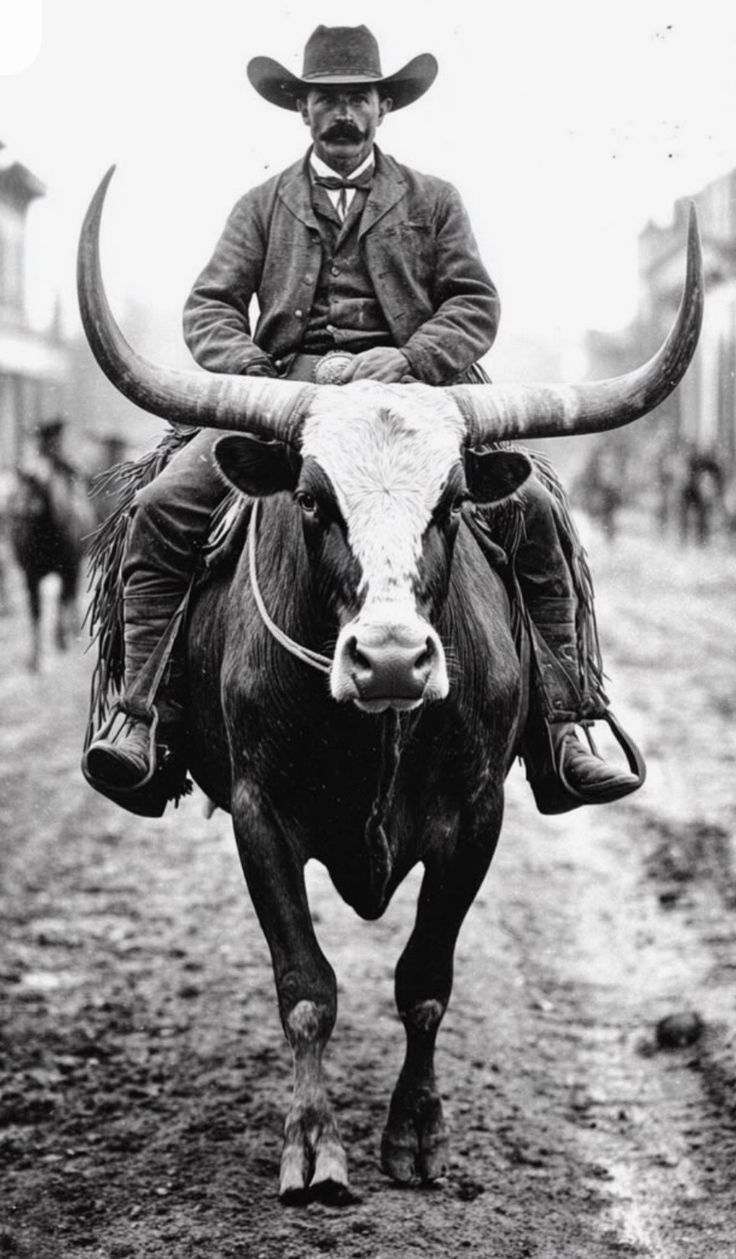

I was a haole, dropped into the heart of the west side, trying to manage a crew of Hawaiian cowboys who showed up in shorts and slippers, smelling like ocean spray and attitude. Guys who’d rather work for their cousin’s cousin than take orders from some mainlander who couldn’t even pronounce Waianae without tripping over his own tongue.

They didn’t trust me.

Hell, I didn’t blame them.

Trust isn’t free out there—it’s earned one busted knuckle at a time.

And this job?

This job wasn’t just gonna test my skills.

It was going to chew on my bones and decide if I was worth swallowing.

OCI was the company I worked for. A big outfit with layers of white management and enough internal politics to drown a moose. They did what most big contractors do when they’re too scared to deal with the crew directly—they installed a buffer. A middleman. A gatekeeper. In our case, that came in the form of a so-called “Safety Officer.”

He was a Mormon Hawaiian—a local boy with a superiority complex and the company’s full blessing to throw his weight around. We used to call guys like that the little godfather. Not because they earned respect, but because they demanded it. He fancied himself a tribal leader, the spiritual bridge between management and labor, but in reality, he was more like a low-rent dictator with a clipboard.

The guy was falling apart physically—fat, red-faced, and wheezing like a broken leaf blower. Every day he showed up in his ill-fitting safety vest like he was the emperor of job site safety, talking down to guys who’d been laying pipe and slinging rebar since before he learned to tie his boots. He wanted us all to believe the company ran through him, that without his divine oversight, we’d all be dead or unemployed. Blah blah blah.

We all knew the truth. He was more politician than safety man, more self-preservation than protection. Rumor was he took kickbacks from vendors at the end of every year. A box of steaks here, a new fishing reel there, a cash envelope tucked into a thank-you card. He played both sides—sucked up to upper management and tried to lord over the trades like he was royalty. Mr. Big Shot, walking around like he built the digestor with his bare hands, when in truth, he couldn’t lift a ladder without a back brace and a bottle of Advil.

He wasn’t on our side. He wasn’t on anyone’s side. He was in it for himself—just enough charm to fool the office suits, just enough bite to keep the crew pissed off, and just enough plausible deniability to never get nailed for anything.

And he was about to be right in the middle of the worst incident on that job.

Then there was the lid crew. The structural steel guys. A band of hooligans out of Gilligan’s Island if Gilligan had neck tats and a rap sheet. Their only job was to assemble and weld the massive prefab lid panels, piece by piece, until the steel crown of that million-gallon beast sat clean on top.

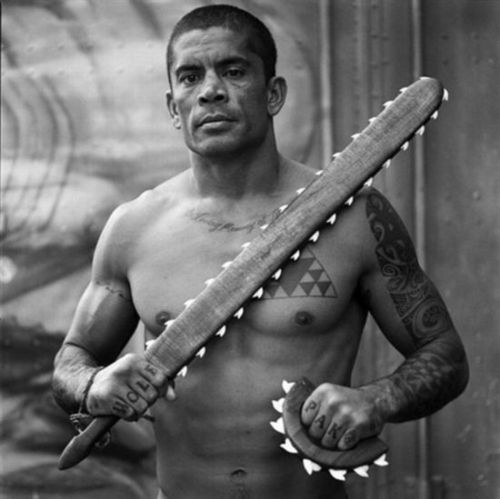

This wasn’t your typical union outfit. These were old Hawaiian lifers—men who bled rust and sweat and carried the weight of five generations of concrete under their boots. Their foreman, Danny, looked like a tribal war chief who moonlighted in MMA. Tatted from ankle to jawline, solid as a boulder, and not one to blink first in a staring contest.

He brought both his sons onto the crew—each tipping the scales at 300 pounds of muscle, rage, and unreadable motives. One of them had just gotten out of jail, face inked up like a mural from Kalihi, and the other didn’t say much but walked around like he was one bad day away from snapping. This was Danny’s show, and nobody else was invited to direct it.

But the real kicker? Danny had the OCI Safety Officer under his thumb. Nobody said it out loud, but it was clear. The Safety Officer—Mr. Clipboard Messiah—suddenly got real quiet whenever Danny entered the room. Like his balls shriveled up under the weight of that tribal stare. If there was a problem with Danny’s crew, it got swept under the rug faster than you could say “OSHA violation.”

I pulled the Safety Officer aside one morning. Quiet conversation behind a Conex box, sun barely up, dust still settling. I told him what was obvious to everyone on the ground: we had an “us vs. them” situation brewing. My crew—pipefitters, crane operators, welders—was getting steamrolled by Danny’s people. Disrespect was daily. Trash talk. Tools missing. My guys being told to “stay the fuck out of the way.” It wasn’t just friction; it was tribal warfare with welding torches.

His answer? “There’s no problem, brother.”

No problem.

I stared at him like he was joking. He wasn’t. He was scared. Or bought. Or both. The kind of scared that makes you speak in whispers and pretend the flames aren’t real while the whole place starts to smoke.

Later that week, I raised it with other managers. Quiet nods, nervous laughs. “Don’t rock the boat,” they said. “Just get the lid up. Once it’s in place, then you can yell, then you can swing the hammer. But not now. Not before the lid.”

That was the goal: get the lid up.

Never mind the division. Never mind the tension that was about to blow. Just shut up, hold your breath, and pray to whatever god welders believe in that we didn’t lose a man before that steel came down clean.

Later that week, I pulled the issue up the food chain. Quiet nods. Nervous laughs. You know the kind—coward’s currency. One of the managers, hiding behind his clipboard, looked up and mumbled, “Don’t rock the boat, yeah?” Another chimed in, “Just get da lid up, braddah. Once it’s in place, den you can yell, den you can swing the hammer. But not now. Not before da lid.”

That was the mission: get the damn lid up. No matter what.

Forget the tribal lines. Forget the resentment simmering just under the surface. Forget that you could feel the crackling tension in the air like ozone before a storm. Just shut up, hold your breath, and pray to whatever rebar god the welders believed in that we didn’t end up dragging a body out from under a thousand pounds of dropped steel.

Weeks passed. I kept waving the red flag. Quiet warnings. Side-door conversations. Whispered truths. But none of it mattered. Tribal bullshit was mounting like surf at Makaha in winter, and nobody wanted to paddle out. Until finally—after all that buildup—the OCI Safety Officer decided to bless us with his presence.

Friday, December 23rd, 2012. Skeleton crew on site. Most of the island already checked out for Christmas. The air tasted like rust and unease.

He came walking in like some ali‘i with a clipboard. Switching his voice into that fake-ass pidgin, trying to win over the locals like we hadn’t seen through his haole act months ago. Flip-flops, fat gut, barking like a dog that had never bitten anything in its life.

Instead of calming the job down, he poured gas on the fire.

Started going crew by crew, threatening the Waianae boys. “You no answer my call? I going fire you, brah.” Demanding they jump when he snapped. Follow his chain of command. Obey his every whim. It wasn’t leadership—it was pure intimidation. A power trip on a dying battery.

Mel wasn’t having it. Mel—sharpest guy I had. One of the few men respected on both sides of the job. He stepped up. Told that fake chief to back off. Stop acting like his clipboard gave him a pair.

Things went sideways quick. Voices raised. Steel and rebar echoing the shouts.

“FUCK YOU!”

“NO, FUCK YOU!”

The kind of shouting that halts the entire site. Welding torches flicker out. Helmets come off. Everyone stops to see who’s gonna throw the first punch.

Then TJ and Sam jumped in—my lieutenants. They backed Mel, demanded answers. Why wasn’t this Safety Officer going through me, the actual Project Manager? Why was he barking orders behind my back like some bush-league kingmaker?

Truth is, he didn’t want my crew talking to me. Because I had upper management’s ear. And he knew the second they heard the truth, his tribal charade was over. Game done. Puppetmaster exposed.

It wasn’t about that one day. It was about the power. And the second my crew called him on it, the illusion shattered.

He came to scare us.

He left knowing he’d lost the room.

Finally, the crane arrived. Massive. Beautiful. Ready to lift. Mel was running it—our top operator. The kind of guy you trust to hover five tons of steel over your head with a smirk.

Sam, our superintendent, had washed his hands of the whole mess. His beef with Danny went way back—bad blood, burned bridges, deep wounds. He folded his arms and let it burn. “Danny’s show,” he said.

Mel too. He’d run the crane but nothing more. No safety input. No talk. No plan review. Just cold metal in motion.

“Let Danny run it,” they said.

So we did.

First piece of the lid went up. Thirty-five feet long, ten feet wide, rigged like a makeshift parade float. Outriggers tied off on both ends. Loose. Makeshift. Sloppy.

Cody was on the tag line. Cody—kid with too much caffeine and not enough brain cells. The kind who got dropped on his head as a toddler and bounced twice. Instead of guiding the lift, he started pulling—like he was trying to win a stuffed bear at the carnival.

The steel spun.

Sam saw it. Could’ve stopped it. Didn’t. Gave Cody a light scolding after, but no action. Danny’s show, remember?

Then came the second piece.

Same chaos. Same Cody. Same twitchy hands and half-cocked judgment.

He yanked again. The steel slipped from the straps. Fell twenty feet down.

Steel on steel.

The second piece landed on the temporary center support, which buckled. First piece came down next, like a tombstone falling sideways.

BOOM.

Steel scattered. Months of fabrication turned to twisted junk.

Litto—our beloved old Filipino welder—was right there. Inches away from getting flattened. You could still see the fear in his eyes an hour later. That thousand-yard stare. Man knew he’d just been ghosted by death.

It wasn’t a mistake. It was a disaster. An almost-body-bag disaster.

Danny? In the thick of it, acting like it was no big deal.

Safety Officer? Barking again, this time trying to pin it on my crew.

Us? Standing in the wreckage. Speechless. Furious.

The next morning, we were called into a “stand-down.” A safety meeting, supposedly. But it wasn’t that. It was a goddamn stage play. Danny and the Safety Officer front and center, performing like TED Talk speakers on a tour of bullshit.

They didn’t ask for my input. Didn’t even acknowledge me. Blamed everyone but themselves.

Mel and Sam tried to call it out. Pointed fingers at Danny’s leadership. But they were shut down. Told to “stand down.” Told to “respect da chain.”

Then Danny got up and said the whole thing could’ve been avoided… with a sign-in sheet.

A fucking sign-in sheet.

According to Danny, the reason two tons of steel hit the dirt was because some poor bastard didn’t scribble his name on a piece of paper. That was his fix.

I couldn’t take it.

I stepped forward. Spoke loud enough for everyone to hear.

“This happened because the OCI Safety Officer interfered. Because we were all told to stand down and let Danny run the show. Because leadership failed. That’s not a paperwork problem. That’s a people problem. And it’s on you, Danny.”

Then I said it flat. “No sign-in sheet gonna fix what bad leadership broke.”

Boom.

Danny lost his shit. Full-on rage blackout. Came at me like a wild boar straight off the mountain—eyes bulging, nostrils flared, tribal tattoos rippling with every stomp.

“FACK YOU! FACK YOU! Nobody talk to me like dat! I gon’ BEAT DA SHIT outta you!”

That wasn’t anger. That was pride, old-school pride—the kind that doesn’t give a damn about safety meetings or chain of command. He saw red. And he had a clean path to me. Took it without hesitation.

Lucky for me, Mel and Sam jumped in—arms locked, legs braced—trying to hold back a freight train fueled by ego and fury. Didn’t matter. He thrashed like a hooked ahi, screaming, spit flying, eyes wild. The tribal leader was done playing diplomat. This was a Captain Cook rerun, and the haole had overstepped.

And what really pissed him off?

I was right.

While Danny was still twisting and yelling in the grip of my crew, his son made his move. Came in from the right, silent, fast—like a fucking hyena with a blood debt. Tattooed arms and sausage fingers swinging wide, face red like brake lights. “I GON’ KILL YOU!” he screamed, lunging at me with all the fury of a son defending his king.

He damn near closed the gap. Inches away. If it weren’t for four crew guys forming a wall in front of me, I’d have had a face full of tribal ink and a busted jaw.

I stood there.

Didn’t flinch. Didn’t blink.

Just locked eyes with Danny while watching his boy try to earn his stripes.

And truth be told?

I wanted ‘em to swing.

I wanted a goddamn reason to lay one of them out. I was ready. The rage was in me, burning like gasoline in the throat. But both of them? No way. I’d be dead before I hit the ground.

And even if I survived, I couldn’t afford to lose the lid crew—not this late in the game, not with the schedule dangling off the critical path like a snapped line on a crane hook.

So I let it simmer.

Waited until the son got pulled off into the background—still barking, still staring daggers.

And then I did the unthinkable.

I walked straight up to Danny. No hesitation. No backup. Mel and Sam looked at me like I’d lost my mind. Hell, maybe I had.

I extended my hand.

Danny’s eyes were bloodshot. His breathing ragged. His pride shattered but holding.

“I neva been talked to like dat in front my crew,” he muttered, quieter now, pain in the voice.

I nodded. “I get it. But I was being honest, Danny. You wanna work this job or fight it?”

We shook. Didn’t smile. Didn’t make peace.

But we shook.

That was the day the job stopped being just a job.

It became a war.

His kids? They kept their eyes on me like sharks circling. Swore they were gonna jump me after shift. I could feel their stare every time I walked by. No aloha in that look—just the silent promise of fists in the parking lot.

It was us and them now.

The line had been drawn—etched in rust, rage, and steel.

And no clipboard, no sign-in sheet, and no bullshit safety talk was ever gonna erase it.

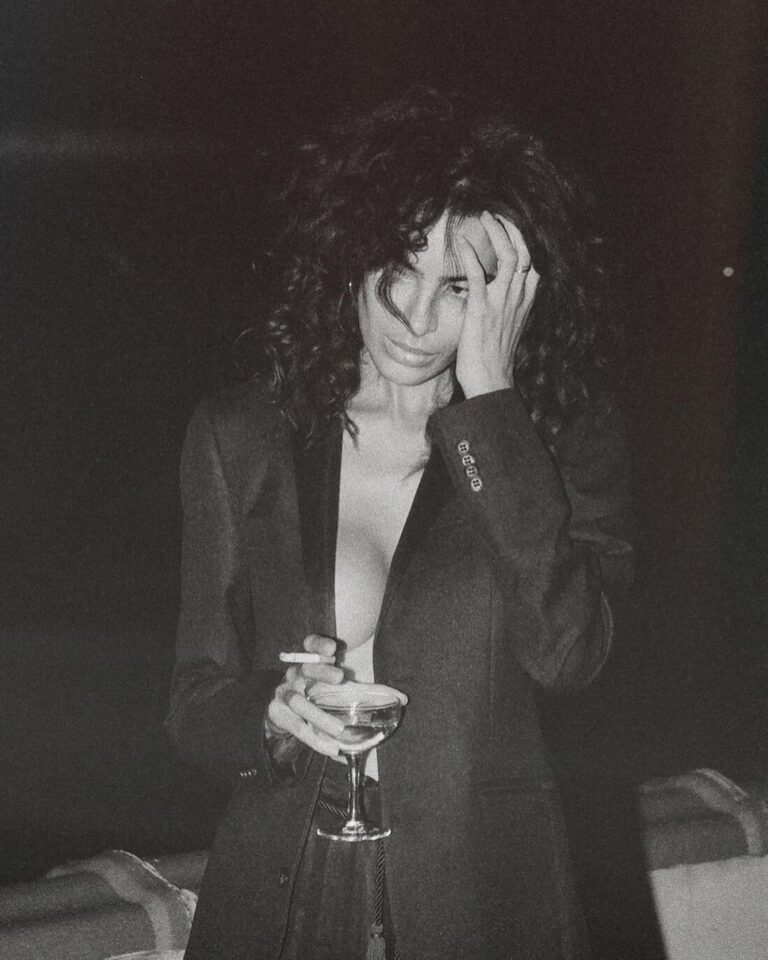

After five years on the west side, I’d earned a little street dust on my boots and more than a few scars that didn’t show on the skin. I brought home west side women—bug-eyed and beautiful in that busted way, all trauma and tattoos. My little condo sat over blue tarps and barking dogs, where the sunrise hit the roof of a pickup like a goddamn blessing and curse all in one. People yelling, fists flying, roosters crowing like it was all part of the same hymn.

It wore on me. Not all at once, but slowly—like rust on rebar.

And then one night, high on shrooms and sick of the noise inside my own head, I looked around that tiny box of a home, saw the faded surf posters and the kitchen I never cooked in, and knew—this was it.

I wrote the resignation letter the next morning with shaking hands and a smile that felt honest. I was done. Done with the politics, the tribal warfare, the sunsets I stopped noticing.

My hair had gone thin and long, orange like a traffic cone in heat. My goatee had bleached white from the salt and the sun. I didn’t look like a project manager anymore—I looked like a guy who barely survived the job.

And maybe I didn’t.

But I left with stories. I left with friends. I left with the kind of tired that sleeps deep.

Time to go home. Wherever the hell that was.