It was a Tuesday night at Amalia’s, another slow bleed toward closing time. The air was thick with the usual apparitions of a tequila bar: stale beer, cheap perfume, and the quiet, simmering desperation of men who were pretending they weren’t lonely. The whole place was a goddamn waiting room for a train that was never going to come.

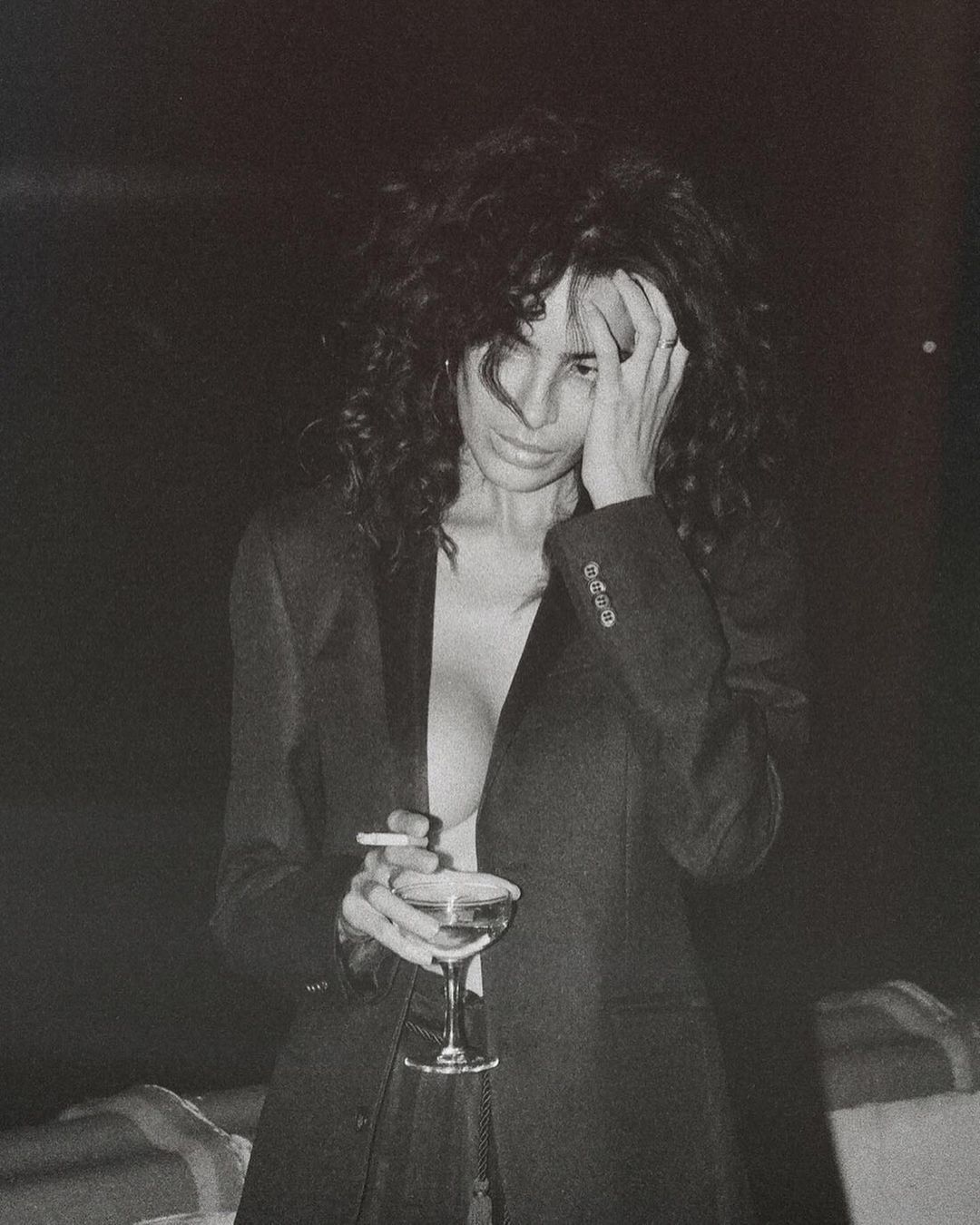

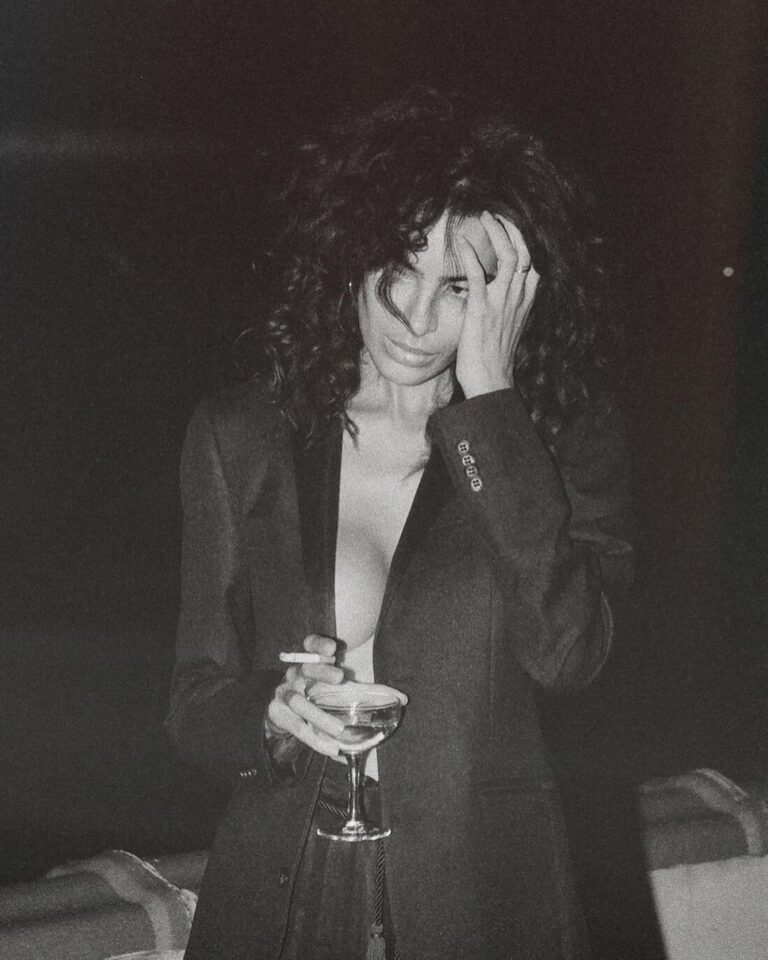

And then she walked in, and the whole goddamn room just sort of tilted on its axis.

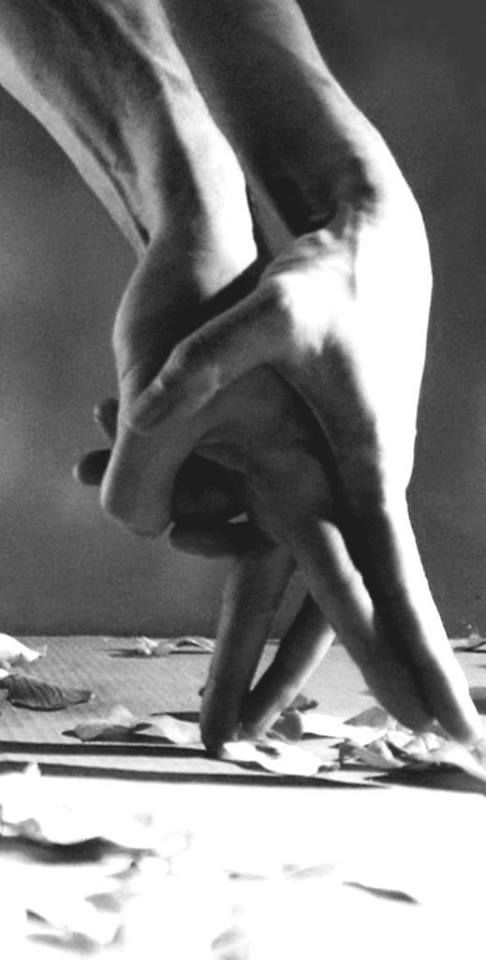

It wasn’t a shuffle, not a strut. It was the kind of walk a woman has when she’s not looking for approval, when she knows the ground she’s walking on is her own goddamn property. She cut through that stale, dead air like a shark’s fin through still water, and every tired, drunken eye in the place followed her.

She had a face that belonged on an old coin, something angry and beautiful that should have been buried for a hundred years. High cheekbones, a strong jaw, the kind of Pocahontas features you see in old, honest photographs, not behind the counter of a goddamn 7-Eleven. Her skin had the color of good whiskey, and she looked like she belonged in a different, more dangerous century.

But her eyes were the main event. They weren’t empty. They were full of a kind of beautiful, intelligent madness. The kind of eyes that have seen the whole goddamn circus and are just waiting for the tents to burn down. They were the kind of eyes that tell you she’s either a genius or she’s going to burn your house down, and you find yourself, for some sick reason, hoping for the fire.

And then there were the breasts. My God. Not the sad, bolted-on things you see on the strippers. These were real. Large, round, perfect things that were practically an invitation to a bad decision. They were built for sin, for speed, for holding onto when the whole world is shaking apart. They were the kind of tits that could make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.

I saw her, and it wasn’t a choice. It was a goddamn diagnosis. The sickness recognized itself. I knew, right then, with the kind of sick, beautiful certainty that only comes from a lifetime of bad decisions, that I had to have her. I didn’t want to know her name. I wanted to know her wreckage.

She was friends with some other girl, Little Lucy, but I didn’t see anyone else. The second she walked in, the whole goddamn room just became a blurry backdrop for her face. And I knew, with the kind of sick, simple clarity you get after years of living in a desert, that I was thirsty.

For three days, I was her goddamn shadow. A cheap suit she couldn’t take off. Every time she walked into Amalia’s, I was there, waiting, a vulture circling a beautiful, wounded thing. I’d buy her drinks until my tab was screaming. I’d tell her bad jokes that died in the air between us. I was trying to buy a piece of her time with my money and my charm, and I was running low on both.

“Come out with me,” I’d beg. “Hang out with me. Let me buy you something.”

Pathetic. A real masterclass in desperation.

But you have to understand, I wasn’t just a horn dog, poking everything that moved in that town. I was on a goddamn journey. A holy war against my own wasted youth. I was making up for twenty years spent in the quiet, sexless prison of a loveless marriage. Twenty years of a dead bedroom. And now I was free, and I was trying to fuck the memory of that cage right out of my own goddamn soul.

She had a kid, of course. They always do.

And a boyfriend. Some low-life who worked at Astro’s down the street. The kind of guy who looked like he was already rotting from the inside out, a walking corpse with a Flock of Seagulls haircut and the pimples of a nervous teenager who was never going to get the girl. He was the guy she went home to, the reason she was sitting here, talking to me.

But he was a good guy, in his own way. The kind of bartender who’d pour you a stiff one and then forget to put it on the tab. A small, simple, and beautiful act of rebellion against a world that was fucking us all over.

I knew the type. We were all just different kinds of animals, swimming in the same goddamn sewer.

I finally managed to drag her out of Amalia’s, down the back stairs to the martini lounge in the basement. A different kind of hell. Darker, quieter, and it smelled of regret and olives.

I had my hands all over her, a clumsy, drunken octopus trying to solve a beautiful, complicated puzzle. But I was getting nothing back. She just sat there, a beautiful, bored brick wall in a tight dress. It was like trying to start a fire with a wet match. I couldn’t figure out the goddamn code. Was I supposed to tell her I loved her? Was I supposed to buy her a goddamn car? She was there, wasn’t she? But it just wasn’t happening.

The second martini hit me, and a kind of beautiful, ugly clarity washed over me. The “fuck it” moment. We were standing at the bar, the air thick with cheap perfume and the quiet hum of other people’s bad decisions. I just laid it on the table.

“Can I go home with you tonight?” I asked her, my voice all gravel and cheap whiskey. “Can I sleep with you?”

We were a comical pair, two drunks laughing at nothing, standing on the edge of a cliff and arguing about who was going to jump first. She looked down at the bar, a little smile playing on her lips, the first real expression I’d seen on her face all night. Then she looked up at me, those crazy, beautiful, dangerous eyes shining.

“See that guy?” she said, nodding to some sad bastard sitting next to me, a lonely-looking sonofabitch with a mustache who was probably just trying to drink himself into a different zip code.

“Yeah?”

“Give him a hickey,” she said, her voice a low, perfect purr. “A real one. On his neck. You do that, and you can go home with me.”

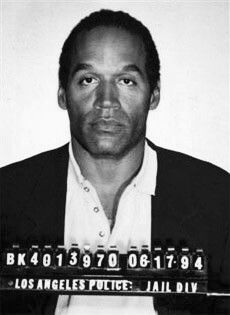

The guy at the bar, the one she’d pointed to, he was a real piece of work. A big sonofabitch with a mustache that had probably seen more sad stories than the bartender, and a hat pulled down low like he was trying to hide from a debt collector or an ex-wife. He looked like he’d just finished a long, hard haul from nowhere and had landed in this shithole to die quietly in a glass of cheap whiskey.

He’d been listening, of course. Everyone in a bar is always listening. It’s a goddamn theater of the lonely, and we were all just waiting for the next act to begin.

He didn’t say a word. Just turned his head slowly, looked right at me with these tired, old, seen-it-all eyes. And then, with a kind of beautiful, exhausted grace, he offered me his neck. Just tilted his head to the side, a quiet, simple invitation.

Like a tired old bull, finally done with the fight, presenting its throat to the matador.

So I did it.

I leaned over the bar, the smell of stale beer and his cheap cologne filling my head, and I latched onto that poor bastard’s neck like a goddamn vampire. I wasn’t gentle about it. I wanted to leave a mark. A receipt for the transaction. A nice, purple bruise that would ask him some hard questions in the morning.

“Holy shit,” the bartender yelled, his voice cracking. “You people are goddamn crazy!”

And he was right. We were. And for a moment, in that cheap, dark, beautiful little corner of the world, it was the only thing that made any sense at all.

I stood back and admired my handiwork. A raw, purple-red flower, blooming on the grimy skin of his neck. He touched it, a strange, tender gesture, and then he looked at me and grinned, a beautiful, stupid, broken-toothed grin. He was proud of it. He was part of the show now.

She just watched, a slow, lazy smile spreading across her face. The kind of smile a woman gets when she’s just won a bet she never expected to. She pulled a crumpled napkin and a pen out of her purse, and with a steady hand, she wrote down her address. She slid it across the wet, sticky bar to me. A contract.

She said she’d be there.

We walked out of that bar without another word. There was nothing left to say. The deal had been made, the price paid. We just hopped in my truck like a couple of bank robbers leaving the scene of the crime, the engine turning over with a tired, old groan.

And we just drove west, into the dark, to go collect on a bad bet.

The second my headlights swept across the front of the house, the door flew open. A little girl, no more than four or five, a mess of tangled hair and big, scared eyes, came running out.

“Mommy!” she screamed, and threw herself into her mother’s arms, clinging to her like a drowning thing to a piece of driftwood.

The babysitter followed, a real piece of work, a worn-out fifty-year-old with the kind of dead eyes that have seen this same sad movie a hundred times before. As the woman I was with carried the kid back inside, the babysitter just stood there on the porch, blocking my way.

“Listen,” she said, her voice all gravel and resignation. “If you give a good goddamn about either of them, you’ll help her. She’s out every night, broke, can’t even cover my pay. The rent’s late. She’s not just falling; she’s already at the bottom of the goddamn well.”

Then she holds out her hand. “Three hundred and fifteen bucks,” she says. “Back pay.”

And just like that, I was the new bank, the lucky sonofabitch who got to pick up the tab for all the other bastards who’d come before me.

I paid. What the hell else could I do?

I walked inside, and the place was a goddamn shipwreck. Not dirty, not third-world, just… exhausted. The kind of place held together by duct tape and quiet desperation. The girl finally crashed, a small, still thing in the middle of the master bed. A casualty. The babysitter, having been paid, vanished like a puff of smoke, a professional who knew when her part in the play was over.

And I waited.

I sat there in the dark, listening to the house settle, listening to the quiet breathing from the other room. I waited until I was sure they were both asleep, the child and the woman who was supposed to be her mother.

I pulled her from the living room, away from the ghosts of her own bad decisions, and into the other bedroom. A goddamn minefield of kids’ toys, cheap plastic shit scattered all over the floor. You couldn’t take a step without crushing some smiling, plastic animal under your boot.

I stripped her naked right there, in the doorway. And in the dim light coming from the hall, with all that childish wreckage around her, she looked beautiful. Goddamn beautiful. A masterpiece in a junkyard. She lay back on the twin bed, on top of a bedsheet covered in Disney characters—Goofy and Mickey and all the other liars, their dumb, happy faces staring up at this sad, beautiful, and completely broken woman.

But the sex… Christ. It was flat. Mechanical. There was no life in it. It was like fucking a statue, a warm, beautiful, and completely dead thing. She wasn’t there. Her eyes were open, but she was a million miles away, probably doing the math on her late rent or remembering some other bastard in some other dirty room. She wasn’t made for loving; she was made for enduring. And you could feel the years of it, the quiet, miserable endurance, in the dead weight of her hips.

So I had to get rough. Not for pleasure. For a pulse. You had to be a little crazy, a little mean. You had to dig for it, to try and find a spark, a nerve, something that was still alive in there. It wasn’t an act of passion; it was a goddamn excavation.

And still, I stayed at it for over an hour and a half. A long, ugly, sweaty piece of work. When it was finally over, we were both a mess, limping, breathing like we’d just run a marathon we didn’t want to be in.

Why?

Because that’s what a man does when a beautiful body is the only thing left on the table, and he’s too goddamn hungry to walk away.

The next day, it was back to the bar, back to the usual routine. Heidi the bartender and little Lucy, rotating them like a couple of bad, scratched-up records, each one playing the same sad song.

But Peom was a different kind of animal. Fun, loud, manic. The kind of beautiful disaster you’re drawn to when your own life is a goddamn train wreck.

We’d been drinking and screwing in the cab of my truck, parked somewhere in the Old Mill District, the windows all fogged up with the steam of our own cheap desperation. And then, of course, she had to pee.

“Piss in this,” I said, holding up an empty beer bottle. A gentleman.

She hiked up her skirt, and I held the bottle for her, a real act of chivalry. And she let go. A warm, steady stream of piss that went absolutely everywhere except inside the goddamn bottle. All over my hand, the seat, the dashboard. A beautiful, golden shower of failure.

And we just started laughing. Not a little giggle. A great, ugly, beautiful fit of laughter, the kind you only have when you’re at the absolute bottom and you realize how fucking funny it all is. And the harder she laughed, the harder she pissed, the pressure of it all just emptying out of her, all over my truck, all over my hand, all over our stupid, fucked-up lives.

And we just sat there, two hyenas in a piss-soaked truck, laughing our heads off.

Yeah, that was fun, back then. That was what passed for fun when you were trying to ruin yourself and doing a damn good job of it.

They were friends, of course. A goddamn tag team. Lucy would be crawling out of my bed, smelling of cheap beer and warm piss, and the phone would already be buzzing. A text from Peom. “Marco Polo?”

It was her goddamn battle cry. A siren cutting through the quiet, hungover morning. I’d be in the bathroom, trying to wash the memory of Lucy off my dick, and Peom would already be at the door, shouting her stupid fucking game into the neighborhood. Announcing to the whole goddamn world that the next shift at the factory was about to begin.

She didn’t care. She wasn’t looking for the same thing Lucy was. Lucy was manic, childish fun. Peom, she was looking for a goddamn exorcism. She wanted something rougher, something more honest. Something that would leave a bruise you could see in the morning.

She’d already been drinking, of course. And she got what she came for.

I gave her what was left of me, which wasn’t much. An hour and a half of the same tired, ugly, beautiful work. A mechanical, joyless fucking. A simple, desperate transaction between two people who were too tired to lie to each other anymore.

When it was over, she just passed out, naked, leaking me into the cheap, sweat-stained sheets. A perfect, quiet, and completely empty victory.

We kept at it, night after night. Just a couple of drunks in a dark room, circling the drain and calling it a life.

She was too young, too wrecked, too goddamn beautiful to be circling a loser like me, but there we were—two crippled pigeons pecking at each other’s scabs. She’d drift between me and her baby daddy, between my truck and my sheets, a broken record skipping over the same rotten track. Then one day she slid into the arms of her Russians, and the needle, and that was that.

Didn’t matter much. Heidi the bartender was already pouring more into my glass, and into my nights, than the girl ever could.

It ended the way everything does—slow, sloppy, inevitable.

She cleaned up, I heard. Some guy told me at a bar, some sad bastard who knew her from back when. Said she went back to the reservation, or maybe it was Indiana, or Oklahoma. Someplace flat and honest and full of goddamn cornfields, a place with no room for the kind of beautiful, ugly apparitions we used to chase in the dark.

The kid, from what I hear, grew up straight enough. Good for them.

And me?

I didn’t find God. I didn’t find a program. I just kept driving crooked, bouncing off the guardrails, until the road, for whatever goddamn reason, just smoothed out a little on its own.

And that’s the whole show, isn’t it? A long string of reckless nights, a parade of bad women with good bodies, and a whole lot of twisted rugs that, every now and then, for no good goddamn reason, just flatten out long enough for you to catch your balance before you fall on your face for good.