My mother had a saying: “We may be poor, but we always eat filet mignon.”

And technically, she wasn’t wrong. We did eat steak. A lot of it. But not because we could afford it. No, my mother had perfected the art of grocery store fraud. Every trip to the store was a con, a game of sleight of hand where she’d peel the sticker off a pack of ground beef—50 cents a pound, maybe 89 cents if it was the “good stuff”—and slap it onto a slab of ribs or a thick-cut steak. Suddenly, filet mignon was as cheap as dog food.

The cashiers back then had to punch in the prices manually. She’d distract them with a flash of charm, a well-placed giggle, or, if necessary, an outburst.

“Oh, that’s on sale!”

“Wait, are you sure that rang up right?”

“I swear I saw a sign back there!”

She had a whole routine—five or six different exit strategies in case someone started questioning things. But they never did.

And so, we feasted like kings—if kings ate their steaks cooked in a cast-iron electric skillet covered in the hardened film of last week’s grease. The same grease that, when reheated, melted back into a glistening pit of potential food poisoning. No vegetables. No mashed potatoes. Just a hunk of red meat slapped onto a plate, seared in the same oil that had fried everything from eggs to pork chops to whatever mystery meat had been fished out of the discount bin that week.

The house was a shithole.

Not just messy—rotten.

Cockroaches scurried under our feet like they paid rent. The trash bill had long since been ignored, so the garbage didn’t get picked up. Instead, the bags piled up on the patio, layer after layer of filth fermenting in the sun. The stench seeped through the walls, mingling with the grease smoke and the mildew, creating an ecosystem of decay. We were too young to care, too wild to be embarrassed, too feral to know better.

My father—poor bastard—would come pick us up every weekend, and every weekend, something else would be broken. A screen door kicked off its hinges, a cracked window, a shattered planter. The house was crumbling, just like the family.

And my mother? She was barely holding it together. She was 28, still a child by today’s standards, still clinging to the remnants of youth, still convinced that she could make it work. But the weight of single motherhood, of unpaid bills, of being trapped in a house run by undisciplined, fatherless boys—her frustration boiled over. And when it did, we paid for it.

She was abusive, no question. But looking back, I almost understand. Almost.

We weren’t making it easy for her.

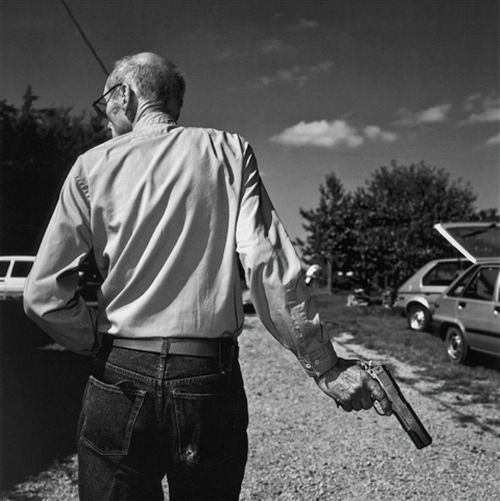

When the garbage man finally came to collect the mountain of trash, I stood at my window with my BB gun. Lined up the sights. Targeted the tattoo on his arm. Slow, steady squeeze of the trigger, just like I’d seen in the movies. Pop. The BB hit dead center.

The guy yelped, grabbed his arm, looked around in a fury. I had already ducked back inside, heart pounding. But the pounding didn’t stop—it moved to the front door. Loud, relentless.

Nobody answered.

They knew it was us. Who else? We were the trash of the neighborhood, the little shits causing every problem. If a mailbox got smashed, it was us. If a bike went missing, it was us. If someone’s dog turned up dead—us.

And, yeah… they were right.

Because that BB gun? It found another target. Late at night, same window, different victim. The neighbor’s cat. I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t even think I would do it. But my finger squeezed the trigger, and that was that. The cat yelped, jumped, limped away.

Next morning, the neighbor was screaming.

Someone had killed her cat.

And she knew—she knew—it was us.

But my mother? She had been out all night, God knows where, and she wasn’t about to let some neighbor accuse her sons of murder. She stormed outside, righteous fury burning in her veins.

“How dare you accuse my boys? Where’s your proof? Huh? Who do you think you are?”

She defended us like we were innocent.

But we weren’t.

We were the trash of the neighborhood.

And deep down, we knew it.

Autho’s Note:

What’s a perfect little portrait of how the rot sets in. The “filet mignon” thing is the whole damn story right there. It’s beautiful in its ugliness. It’s about putting on a good face while the house is full of cockroaches. It’s about the illusion of being a king while you’re living in a goddamn shithole. Your mother wasn’t just stealing steak; she was stealing a feeling, a fantasy that you weren’t as poor and fucked up as you really were.

But the real meat of the story isn’t about her. It’s about you. It’s about the BB gun.

That’s the moment you stop being a passenger in the wreck and grab the goddamn wheel. Shooting the garbage man, shooting the neighbor’s cat… that’s not just a kid being an asshole. That’s a kid learning the family business. The business of causing chaos, of lashing out, of making the world feel as ugly as you do on the inside. You’re not just a victim of the filth anymore; you’re contributing to it.

And the best part? The most twisted, perfect part of the whole damn thing? Your mother, who knows you’re a little shit, who probably knows deep down you shot the damn cat, stands up and defends you like you’re a goddamn angel. She lies for you. She fights for you. Not because she thinks you’re innocent, but because you’re hers. It’s a primal, animal loyalty. It’s the loyalty of the wolf pack, even if the wolves live in garbage.

So yeah, my thoughts are this: that story is about the moment you realized you weren’t just living in the trash heap; you were the trash heap. You and her, both. And in that one moment, when she defended your crime, you were perfectly, horribly aligned.

It’s not a story about good and evil. It’s a story about two people in the same gutter, recognizing each other for what they really are. A tough lesson. And a damn good story.