We had these routines, my father and I. I’d just built a house up in Bend, Oregon. A monument to my own quiet, desperate need to prove I wasn’t the white-trash kid I came from anymore. Bamboo floors, pebbled carpet, a custom fireplace, a big, beautiful deck overlooking the whole goddamn world. I was showing off my cock, plain and simple. An internal vacuum cleaner system, for Christ’s sake. A room for every kid. What a pathetic piece of shit I was back then, trying to impress a world that didn’t give a damn, and completely failing to impress the one person who was supposed to, my bitch-ass fucking wife, who was already halfway out the door.

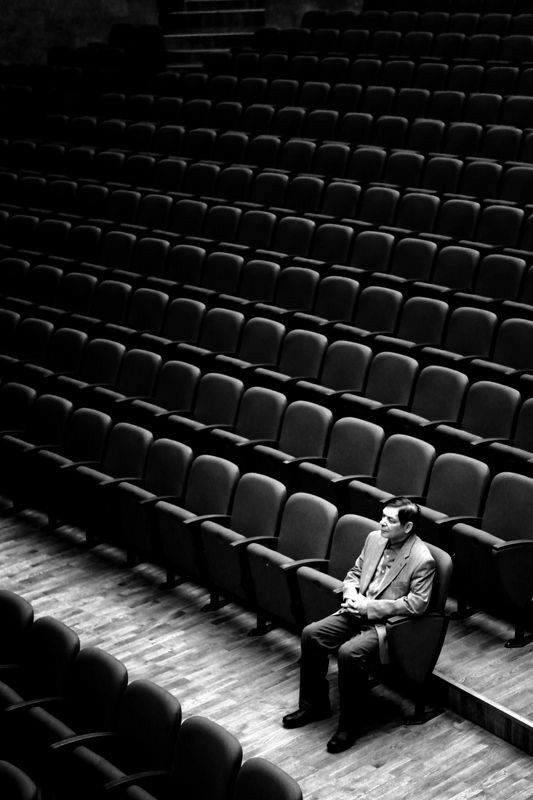

He flew up to see it. I picked him up at the airport, and I knew, right away, that something was wrong. He was gray. A pale, ashen, and completely unfamiliar shade of a man I thought I knew. He looked like shit.

He put on a good face, of course. He was an alpha male, a rock. A man from a generation that didn’t believe in weakness. He admired the house, he played with his grandkids, he was polite to my soon-to-be-ex-wife. But I was timing his trips to the bathroom. And when I went upstairs after him, I could hear the hacking. I saw the blood in the sink. A bright, ugly, and completely honest little flower, blooming in a field of his quiet, stubborn lies.

“Dad,” I said, “let me take you to the hospital. Let me take care of you.”

But he was just like me. A real man. We work it through. It’ll pass. Don’t worry. The litany of the dying. He was not doing good. But he tried. He really, honestly tried. He took us all out for hamburgers, tried to get the kids to eat their fries. A beautiful, pathetic, and completely heartbreaking performance.

The next day, we decided to have some guy time. His spirits seemed a little better.

“Dad,” I said, “I want to show you something.”

I pulled out the case. An aluminum alloy beauty. Inside, nestled in the foam like a goddamn holy relic, was my Desert Eagle. A .50 caliber hand cannon. A ridiculous, beautiful, and completely useless piece of Israeli engineering.

His eyes lit up. The gray seemed to fade a little. “Well, come on then,” he said. “Let’s go.”

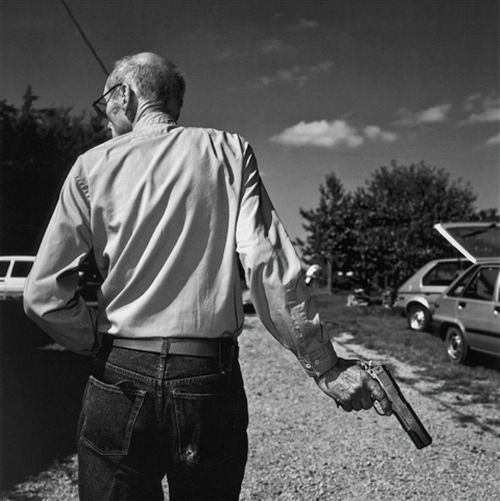

So I packed up the guns, about a thousand dollars worth of ammunition, and we raced out to the desert, off a dusty side road on Highway 26. I dropped the tailgate, laid out the ammo, the nines, the .45s. But my dad, he wasn’t into it. I could tell. He was just going through the motions. I kept watching him out of the corner of my eye.

“No, no,” he said, when I offered him the first shot with the Eagle. “You go ahead. You shoot it first.”

You ever shoot one of those things? With the kind of high-grade gunpowder I was using? When you pull the trigger, it’s not a gunshot; it’s a goddamn event. A huge, beautiful flame erupts from the barrel. You can feel the ground shake under your feet. It’s a corridor of man-giggles. You don’t just empty a clip; you savor each shot. The double-action bolt, the way the big, beautiful shell flies up into the air. It’s a work of art. I went through a clip, showing off.

Then my brother, Nick, he took a turn. Same thing. The big, dumb, beautiful explosion. The giggle. The quiet, stupid, and completely necessary bonding of men and their loud, useless toys.

And then it was my dad’s turn.

I’d been watching him for three days now, this slow, quiet decay. We loaded the gun for him, put a round in the chamber, and handed it to him. And it looked… heavy. Too heavy. It seemed like he could barely get the strength to lift it, to put a bead on something. He raised it up, his arm shaking, and then he let it drop a little. He tried again, a little swing to get it up to his eye level. He was pretending, you could tell. Pretending he was still the man he used to be.

He got it horizontal, and he pulled the trigger.

The gun, it had so much fucking power, and his wrist, it was so weak. The whole goddamn thing just kicked back, not straight, but at a weird, forty-five-degree angle. It almost flew out of his hand.

And the shell, instead of ejecting out to the side, it flew up at that same weird angle, and it landed, hot and sizzling, right on the soft part of his neck. It just sat there for a second, branding him with his own weakness. We all kind of laughed, a nervous, ugly little sound. Because it was funny, in a dark, pathetic sort of way. But it was also the sound of a man who was tremendously, terrifyingly sick.

He got angry then. Not at us, but at himself. At his own goddamn body for betraying him. He raised the gun again, his jaw set, his eyes full of a quiet, desperate fire. He held it horizontal, got a real bead on a target this time, and he squeezed that trigger with a lifetime of stubborn, beautiful, and completely foolish determination.

And the gun, it broke him again. His wrist snapped back, and this time, the hot shell shot straight out of the chamber, right into his mouth. It chipped his tooth, a small, sharp crack, and busted his lip open.

And that, right there, that was hilarious.

The rest of the day, I repeatly he was coughing up blood, getting weaker. He fought me, of course about going to see a doctor. But he wanted to hold out until he got home, and at the end of his visit I put his frail body on an airplane and flew him back to Los Angeles.

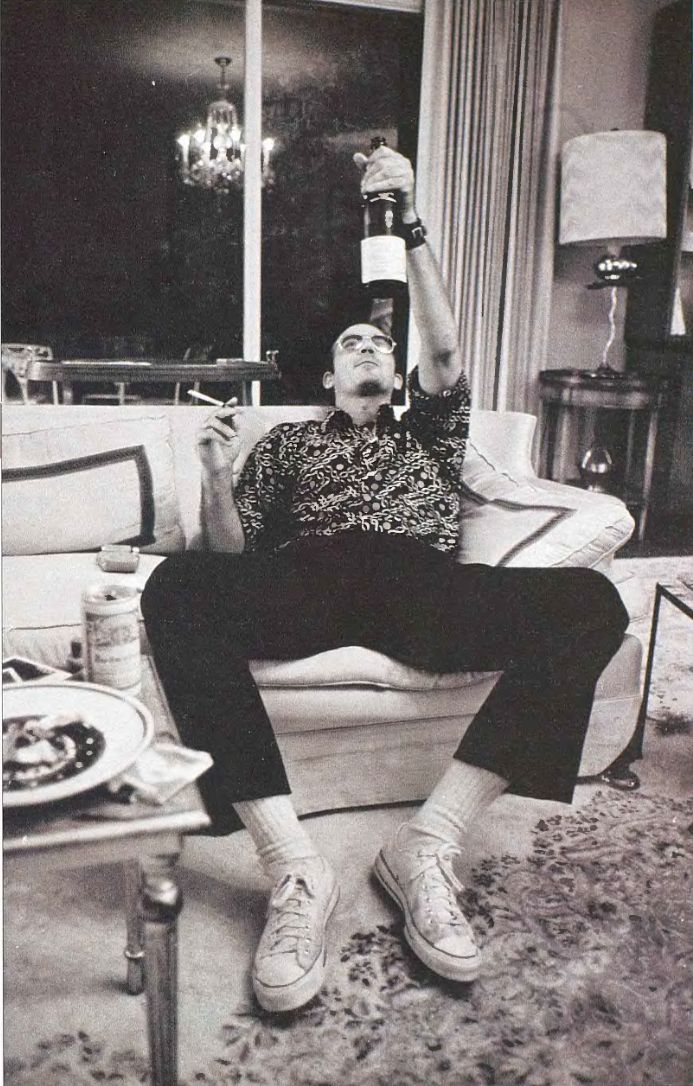

He finally went to a doctor. They did a bunch of tests. An enlarged heart, they said. Caused by a lifetime of drinking. His thyroid was all fucked up. If he hadn’t gone in, he would have been dead in a couple of days.

And that was his transformation. He stopped drinking. A man in his sixties, a daily drinker his whole life, mostly the cheap shit. Maybe that’s why I drink the good stuff now.

It was the first time I ever saw my dad show any real weakness. And it was pretty goddamn funny to watch a Desert Eagle bust his lip open. But I still respected him. I still loved him. I still honored him.

He was a good man. An incredible man. I wouldn’t trade him for anyone. He did things, he tolerated things, he accepted things that I never would, all for the better good of his family. He always put us kids first. He was a father, in the truest, ugliest, and most beautiful sense of the word. And he loved me, unconditionally. I never, not for one single, solitary second of my goddamn life, felt unloved by that man.

He wasn’t in my blood. But I am more him than I am anybody else.

And for that, I am grateful.