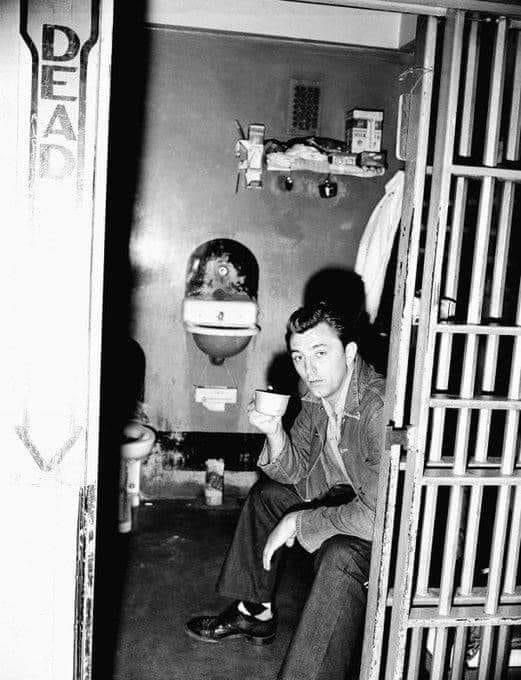

You have to understand, just getting on that boat was a goddamn miracle. I’d been through the fire, talked my way back into the Navy after a “misunderstanding” that involved me, a commander named Douglas, and a judge advocate who seemed genuinely surprised I hadn’t actually killed the sonofabitch. I got clemency, a beautiful, clean, and completely undeserved second chance.

So they flew me from San Diego, ripped me away from a brand new, beautiful wife, and dropped me onto the deck of the USS Independence. A million-dollar-a-day floating fortress. And what was my new, glorious, reinstated-to-the-Navy job?

I was an E1. A swabbie. The lowest form of goddamn life in the sea.

And my first, beautiful, and completely soul-crushing assignment was in the scullery.

Yeah, the mess hall. The “s***** side.” That glorious, stinking hole where the trays come in, piled high with the half-eaten garbage of 5,000 other men. My job? Scrape the shit into a trough, spray it down with a high-pressure hose, and feed the beast—the giant, rattling, and completely indifferent dishwashing machine. A glorified dishwasher. It’s the same goddamn job they give you in boot camp to break your spirit. And here I was, a grown man, a shipyard man, flown across the world to separate the spoons from the forks. It was beautiful. It was perfect. It was the most expensive goddamn dishwasher in the world.

But the winds of war, they’re a funny bastard.

My squadron, the VS-37 “Vikings,” they got sent home. No more submarine threat, they said. So they packed up our planes, all our gear, and just… flew off. Leaving a handful of us beautiful, useful, and completely orphaned bastards behind.

And then the real show started. The A-6s came in. The F-18s. The supply boats started showing up, day after day, a long, quiet, and completely terrifying parade of death. We weren’t a carrier anymore; we were a floating goddamn bomb. The hangar bays were full of these incredible, sci-fi-looking missile systems, just sitting there, no place to store them. The machine was getting hungry.

And in the middle of this beautiful, chaotic, and completely honest buildup, I get a call. The Commander wants to see me.

He looks at my file. “It says here you were a ‘Nuclear Loader.’ Is that true?”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

He was talking about the B-52s, the big ones, the ocean-droppers. The kind of bomb you had to load on a quarterly schedule, against a stopwatch, because if you fucked it up, the whole goddamn squadron failed.

And just like that, the dishwasher was dead.

I traded my white apron for a red jersey. The color of the “ordies.” The color of fire, of targets, of all the beautiful, ugly, and completely necessary things that make a war a goddamn war.

My new job was on the flight deck. And it was a beautiful, ugly, and completely exhausting ballet of death.

We called it the “Attack Fives.” Twelve hours on, twelve hours off. We’d be fusing bombs while the first squadron of five planes was taking off. As they were leaving, we’d be loading up the next five. As they were getting catapulted into the black, the first squadron would be landing, their fuel low, their racks empty. The fuel guys would hit them, we’d hit them, load them back up with more beautiful, ugly bombs, and they’d taxi back to the catapult. A constant, relentless, and completely glorious cycle of organized chaos.

You’d be working, your body aching, and you’d catch something out of the corner of your eye. A flash on the horizon. I was just a kid, 21 years old, and I couldn’t figure out what it was. And then I focused.

Tomahawk missiles.

A beautiful, silent, and completely terrifying light show. Our sister ships, the cruisers and frigates surrounding us, were doing their night ops. Just shooting these goddamn things off in every direction, like a Fourth of July party in hell. With two submarines under us, that carrier was the safest goddamn place on the planet.

And the mission? Christ. It was simple. The Iraqis were trying to run out of Kuwait. Our job was to make sure they died.

It’s funny, the things you see after the fact. We didn’t have internet, no instant news. We were just loading the bombs, sending the planes. It wasn’t until later you see the pictures of that road, that “Highway of Death.” The charred bodies, the burned-out tanks. Of course, they were all looters, so you didn’t feel that bad. But our guys, that’s all they did. They just took out anything that moved on that road. A beautiful, efficient, and completely brutal piece of work.

We did that routine for weeks. My body was a wreck. I was still trying to work out, but after a 12-hour shift of loading bombs, your body just… quits.

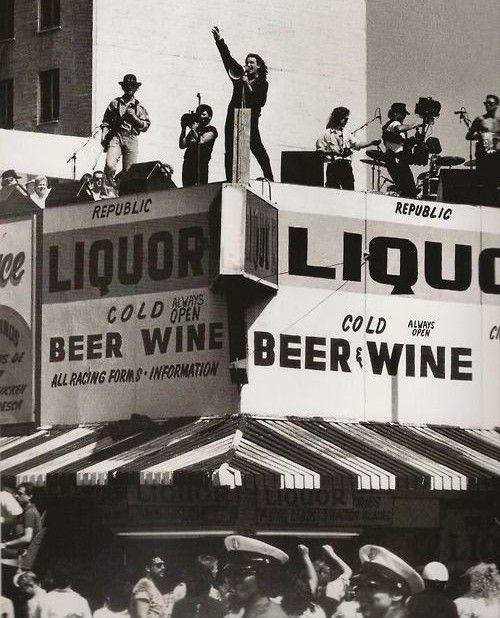

We were out to sea for five months straight. No port. And when you coop up that many men, that much testosterone, in a steel box for that long, the animal in the cage starts to get restless. Fights, left and right. So they gave us a “Beer Day.” They shut the whole goddamn boat down. Two beers. Two beautiful, ice-cold, and completely necessary beers for every man. The whole flight deck turned into a beach party. Guys in their bathing suits, some bastard playing a guitar. A beautiful, ugly, and completely surreal picnic, surrounded by an ocean that was, I shit you not, full of goddamn sea snakes. You could see them, swimming around. A perfect, beautiful, and completely honest reminder that even paradise has its fangs.

After the USS Midway finally came to relieve us, we headed for home, stopping in Singapore, or Hong Kong, or some other beautiful, degenerate port-of-call.

And the punchline? The beautiful, ugly, and completely hilarious joke at the end of my whole goddamn naval career?

I got my honorable discharge. I got a ribbon for it. I am, officially, a “Combat Veteran.”

And I went in an E1… and I came out an E1.

A perfect, beautiful, and completely honest circle. I went across the world, I saw a war, I washed the dishes, I loaded the bombs, and I came back exactly where I started.

And you know what?

It’s one of the coolest goddamn things I’ve ever done.