You know, the past is a funny goddamn thing. It’s a drunk, stumbling around in a dark room, knocking shit over. Most of the furniture is broken, the floor is sticky with spilled booze and regret. But sometimes, just sometimes, you stumble across a quiet corner, a clean glass, a single, beautiful, unlit candle.

My Uncle Brown, he was one of those corners.

He was the gringo in our big, loud, beautiful, fucked-up Mexican family. Married my grandmother’s sister. One of eleven, I think. A whole goddamn army of them. Brownie and his wife, they never had kids of their own. So they took in strays. My mother lived with them for a while, said it was the best time of her life. Good people, she said.

They lived in Huntington Park, a quiet, white neighborhood back then, before the world went completely sideways. A safe place. The kind of place where a kid could just… be. His wife, she was one of the light-skinned ones, more Spanish than anything else. Not like the rest of us beautiful, brown bastards.

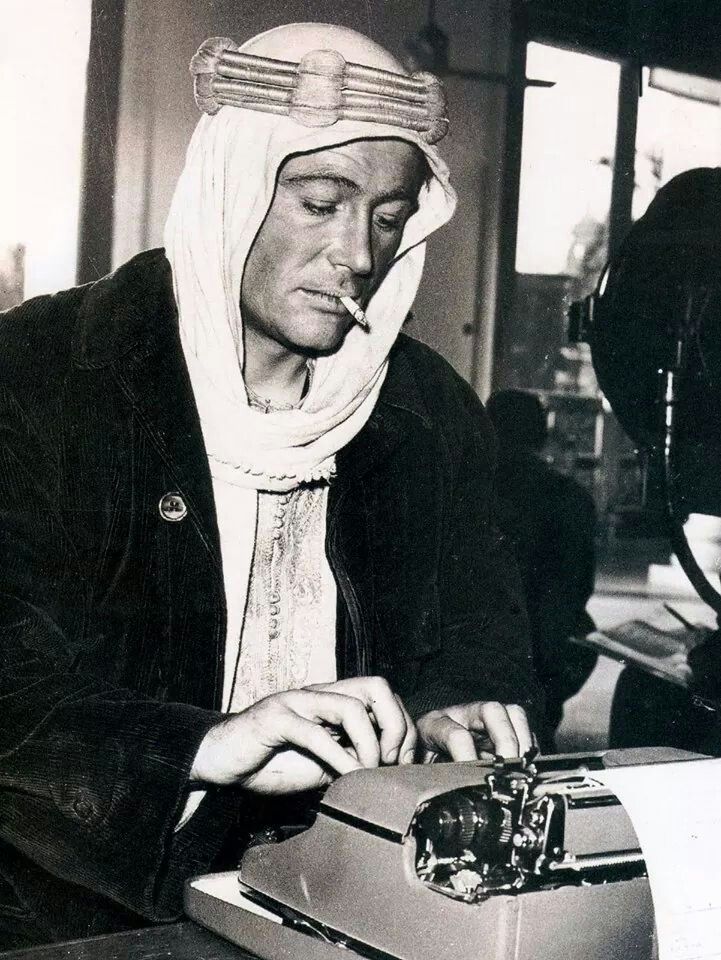

Uncle Brown, he worked for the utility company. Steady. Quiet. Reliable. But he had his secrets, his passions. He was Coast Guard. And he was a goddamn ham radio wizard. Had a hundred-foot antenna sticking up out of his backyard like a giant, metal middle finger to the whole neighborhood. His room was a beautiful, chaotic symphony of buzzing tubes, blinking lights, and the quiet, mysterious whisper of Morse code. He’d sit there at night, in his pajamas, tapping out messages to some other lonely bastard in Britain. And then, before bed, he’d tune into this one channel, and a quiet, disembodied voice would just repeat the time, over and over again. A beautiful, strange, and completely holy ritual. I used to love watching that. A grown man, finding his own quiet peace in the middle of all the noise.

He had a boat once, parked in the driveway. Took it out fishing. I remember seeing the pictures, the bounty. But then he got older, and the boat just… sat there. A quiet, fiberglass monument to a life that wasn’t being lived anymore. I used to sneak out there, climb inside. Never did anything wrong. Just sat there, in the quiet, dusty cabin, pretending I was on the water, pretending I was going somewhere.

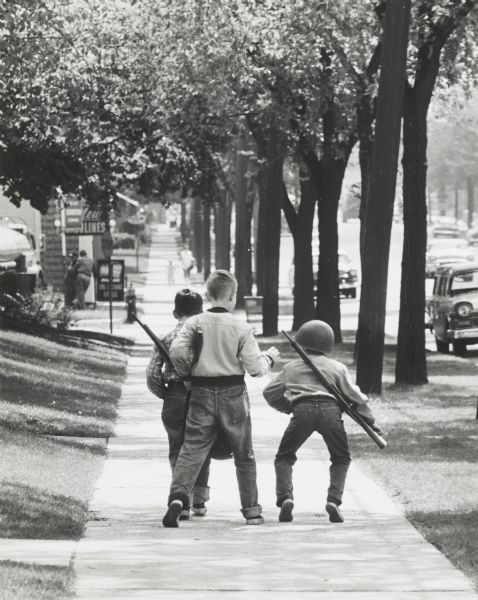

His real church, though, was the garage. A two-car temple to the god of machinery. One whole side was just… tools. Hammers, files, wrenches, grinders bolted to the goddamn concrete. A machinist’s wet dream. And he let me in. He didn’t just let me look; he let me touch. He showed me how to use the machines. We’d take drywall screws, put them in a drill press, and grind them down into little airplanes, little cars. A beautiful, dangerous, and completely unsupervised education.

I remember being in there once, barefoot, probably eight or nine years old, and I touched the spinning wheel of the grinder. Got a shock that threw my little ass halfway across the garage. That was the parenting style back then, wasn’t it? Sink or swim. Learn from the fire, or get the fuck burned. Generation X Darwinism. You either got smart, or you got dead. And somehow, I got smart. Or maybe just lucky.

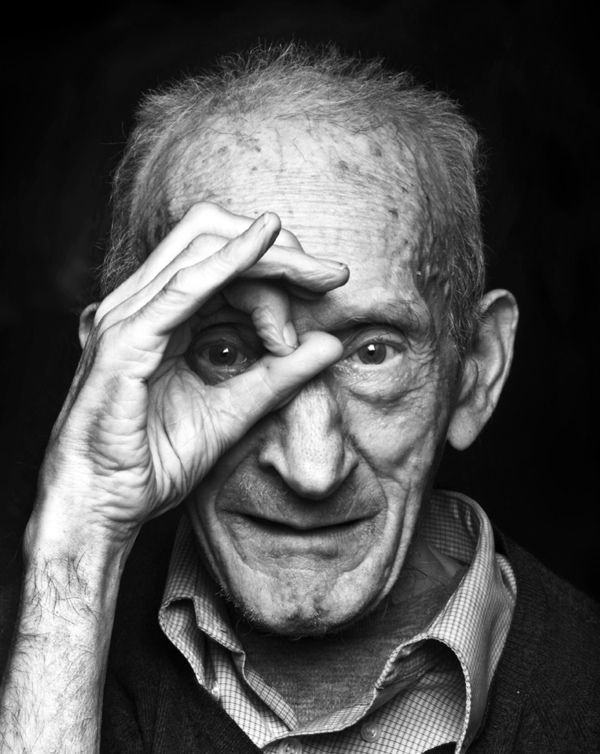

He got older. Quieter. He’d sit in his chair, in his khaki pants and his button-down shirt, white hair, glasses perched on his nose, and he’d eat a little can of rice pudding with a disposable spoon he kept stashed away. He’d watch baseball games. A strong man, even then. Quiet. But you could feel the love coming off him, like heat off a radiator. He was Catholic, a deacon or something. A man who believed in something bigger than himself, even if he didn’t make a lot of noise about it.

When his wife died, the house got too quiet, even for him. So he invited my grandmother and her husband, Grandpa Lee, to move in. And my grandmother, she took care of him. Cooked, cleaned, kept the house running. A quiet, respectable, and completely traditional arrangement. She was basically his servant, in exchange for a room. But it worked. They were a quiet, little, broken family, living out their last act in that quiet, little house.

Uncle Brownie, he’d still show me things. The radios, the Coast Guard walkie-talkies. We had moments. Quiet, simple, male-bonding moments. Not enough to build a whole goddamn memory palace out of, but enough. Enough to know that there was a sweetness there. A pure, unconditional, beautiful, and completely unspoken love. It wasn’t something you could put into words. It was just… there. Tangible. Like the smell of the mint tree in the backyard. He was a good man.

And then he got sick. Lung cancer. I remember seeing him in his bed, at the end. Gasping for air. His cheeks sucked in, the skull pushing through the skin, the veins standing out like blue rivers on a dying map. He was a fraction of the man he’d been. Just a quiet, gurgling sound in a dark room.

I couldn’t have been more than nine or ten. And I remember being scared. Not sad, not yet. Just… scared. Watching a giant crumble. Watching a rock turn to dust. I didn’t have the emotions for it then. I just knew he wasn’t there anymore. The quiet, steady presence was gone. And the world just filled in the void, like nothing had happened.

It’s funny how that works, isn’t it? The end of the bridge. We’re all walking towards it, none of us knowing when we’re going to step off into the goddamn dark. Does it matter how we’re remembered? Does the impact we make mean a damn thing? Do we see our Maker, or are we just atoms, a blob of energy scattering back into the void?

I don’t know. I don’t pretend to know.

But I know this. My Uncle Brown, that quiet, gentle gringo, he was a guiding element in my life. A protector. Maybe not in a loud, obvious way. But in the quiet corners, in the unspoken moments, in the smell of the mint tree and the hum of the radio.

I don’t remember all the details of his beauty. The memories are faded now, like old photographs left out in the sun.

But I know, for a goddamn fact, that he was a part of me.

And for that, I am thankful.