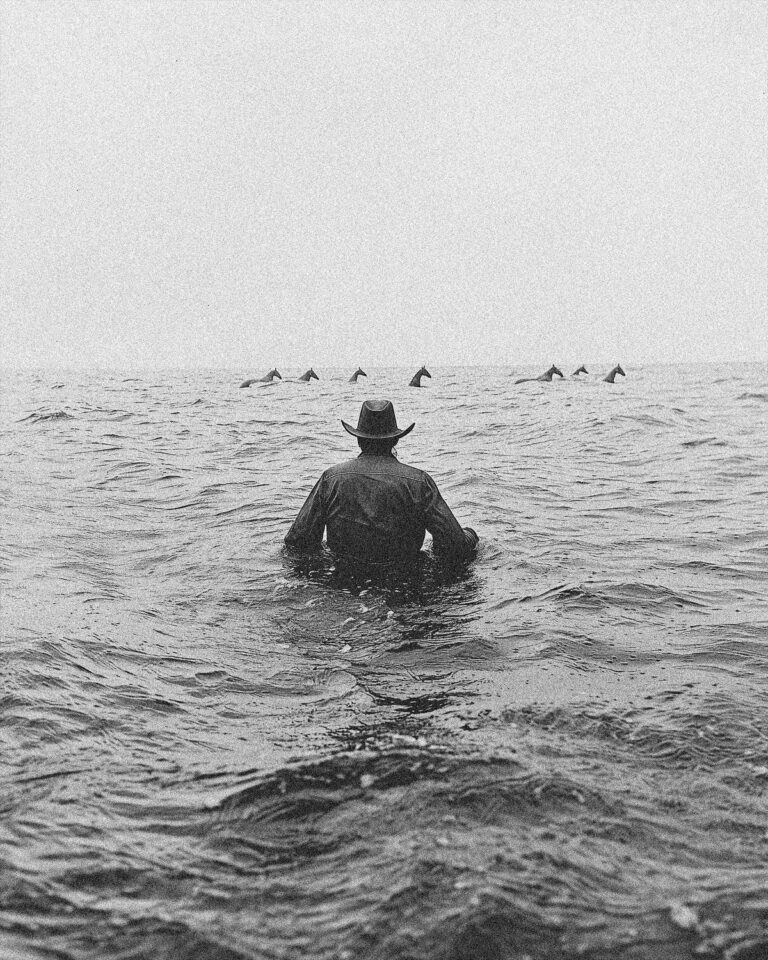

My Grandpa Johnny, he looked like that guy from I Love Lucy. Desi Arnaz. Had that same thin mustache, right above the lip, always perfect. He was a handsome man, charming, but he didn’t speak the same clean Spanish as my grandmother; his was the rougher, border-town version. He was a first-generation wetback, as they used to say. An original who floated himself across the river to get here. I never met any of his other family. He was the start of the line.

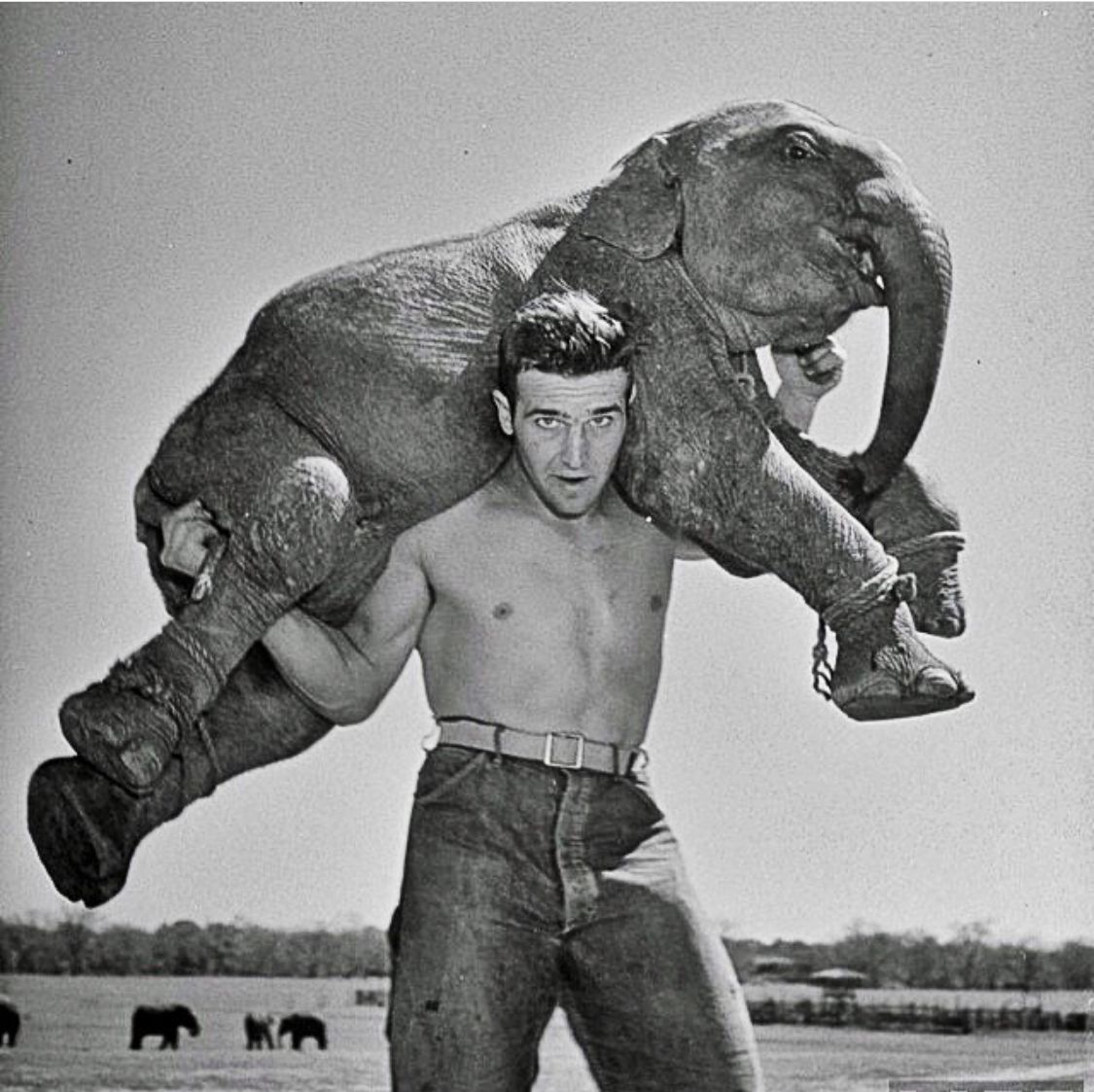

He was a good-sized man, strong. Got himself a job at the Farmer John

slaughterhouse in Bellflower, back before all the residential houses went up. The place was surrounded by these twenty-foot walls, and they’d painted these Mural of happy murals on them—white people on a farm, milking happy cows. A goddamn lie to hide the absolute carnage that was happening inside. On a bad day, you could smell the death, the burn of whatever was left over.

My grandfather worked the floor there. He told me one of his first jobs was to handle the cows. He was a strapping young man. He’d get beside a cow, wrap his arms around it’s head, and use his thumb—digging the knuckle into the soft spot underneath its jawline, then pull back with all his might while tweaking its neck like a chokehold. Using his thumbs would soothe the animal, make it stop fighting. And while he held it there, calm and still, another guy would come up from behind with a sledgehammer, stand over the cow and my grandfather and, with one full swing, crack its skull open. You could hear it, he said. A deep, wet crush. And the cow would just drop, gone. Then Grandpa would go out and grab the next one. That was his job: using his strength to soothe an animal right before its execution.

Eventually, he moved up. Got himself a couple of knives, which he always kept sharp, even when he was old, reminiscing about his skills. Part of the deal was he got to bring home meat, huge sticks of salami. But the years of being a butcher, of hard labor, they took their toll. He got out on a pension, his hands already starting to curl up from carpal tunnel. Life was supposed to be good.

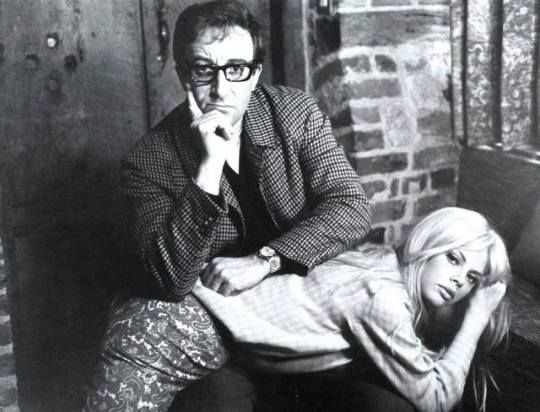

Late at night, after my grandmother was gone to sleep, my grandfather and I would stay up until eleven to watch The Benny Hill Show. Kind of risqué for the time, girls with their tits half hanging out, all that suggestive bullshit. It was a good time. A strange kind of male bonding, the old man and me, the little man, as he always called me. He was always impressed with me, telling me how the neighbors wanted me to marry their daughters. He’d tell me weird shit, too. His philosophies. “An army guy has a woman at the base and off base,” he’d say. “But a navy guy? He has a woman in every port.” And the one that stuck with me: “You never pay a woman to have sex. The money is for them to leave.”

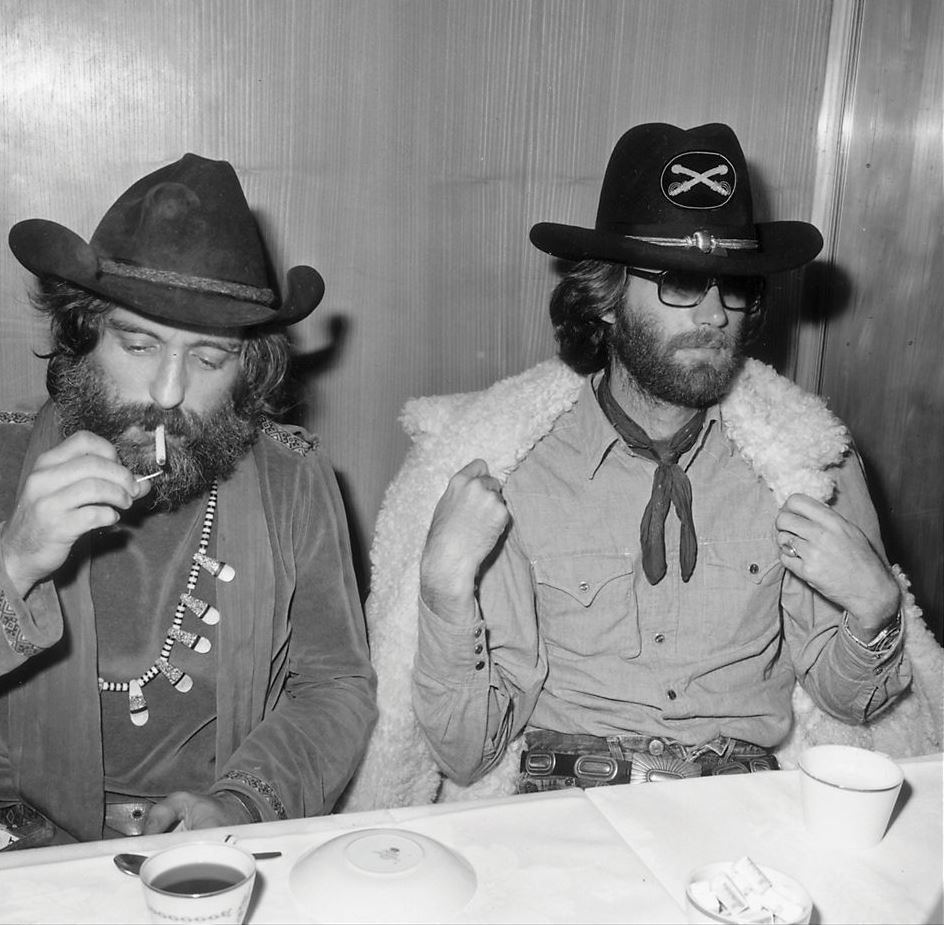

He went through his own mid-life crisis. Started buying gold nugget watches and necklaces, acting like some kind of aging gigolo. His body was getting older, into his late sixties, and he decided he’d dye his graying hair and beard with a black Sharpie. He didn’t realize if you washed your hair, it would all just run down your face. So he’d just slick it back with VO5, smelling like a damn flower shop, and go out to enjoy the good life. My grandmother would find matchbooks from strip joints in his pockets when she did the laundry and give him hell for it.

He took up a new hobby: collecting cans. He’d walk the streets with me, going through dumpsters and people’s trash. He had this coat hanger he’d straightened out, with a little hook bent at the end, and he was a real artist with it, able to snake out a single aluminum can from the bottom of a bin. We were collecting them for my Aunt Yoli and her kids, not that they needed it, but they were the ones who always squeaked the loudest.

One day, we were behind a grocery store and hit the jackpot: a dumpster full of produce they were throwing away. Tomatoes, oranges, all of it still in good condition. We filled four sacks with the stuff and raced home. When Grandma Bertha saw it, she almost kicked us both out of the house. “We’re not hobos!” she yelled. “Digging through people’s trash!”

Then the VA started mailing him his medication. Every day, a new vanilla envelope with a new bottle of pills. Pretty soon, the TV tray next to his chair was packed with them. He didn’t know what was what, just took them all, a handful of pharmaceuticals without any real direction. And his personality started to change.

One day, he drove Grandma up the Whittier hills to clean a doctor’s house who she had been cleaning his office. It was a nice place, very impressive views and my grandpa discovered the wine section of the house and found a little bottle of wine, cracked it open, and started sipping on it. That, plus all the medication… It was not a good combination.

It was time to leave the doctor’s house. We all piled into the car. He was driving his new car, the one with the stick shift he didn’t know how to handle, and I could tell right away he was out of his goddamn mind on those VA pills and that cheap wine.

Right out of the driveway, the downhill slide began. The car moved in a kind of lazy, zigzag pattern down that rich person’s street. That first left turn was a little too fast. The second, a hard right, the wheels screeched on the pavement. That got my grandmother’s attention. She started yelling his name in Spanish.

I could see the panic in his eyes. He was pumping the clutch. Pumping it like he thought it was the brake, thinking he was slowing down while the damn car was just picking up speed, rolling faster and faster down that hill.

He damn near missed the last left turn, the wheels screaming, the car jerking hard as it hit the curb but just kept going forward, faster now. The air in that car was pure panic. My grandmother yelling, him grunting and fumbling. It was crazy.

We started into the last right turn before the big intersection at the bottom of the hill. He hits the curb—BOOM—and the car kind of slid along it, not slowing down at all. Grandma was screaming, a high, thin sound. He’s in a full-blown panic now, can’t take his eyes off the road because things are going too fast, but can’t look down to find the damn brake.

There was a car parked at the curb ahead. He hits that curb again, then the back of that parked vehicle.

BOOM.

An intense, violent, final stop.

Grandma went flying into the windshield. No seatbelt. Her face was all cut up. It was not a pretty sight. Grandpa had straight-armed the steering wheel, and the whole thing was bent to shit from the force of his arms and his face smashing into it.

Me? I was in the back, no seatbelt. I just slammed into the back of the front seat. Got a little cut up.

That was it for Grandma. She went out and got herself an annual bus pass after that. Swore she’d never ride in Grandpa’s car again.

And she never did.

And then, he finally got sick for real. Lung cancer, spreading through him like a weed.

I went to visit him at the hospital in Lynwood, California. I walked inside, and this weird, heavy feeling hit me immediately. Flashbacks. The smell of the place, the look of the flower shop, the bored face of the receptionist—it was all familiar, like a dream I’d had before. It freaked me out. I mentioned it to my grandma, and she just looked at me, her face calm.

“Mijo,” she said, her voice quiet. “This is where you were born.”

Christ. The place they haul you in to die is the same damn place they pulled you out of, screaming and covered in blood. A perfect, rotten circle.

We eventually took him home. He took over Uncle Brown’s old bedroom, and he went the same way as Uncle Brown. The lung cancer took him slowly, with every wet, gurgling breath. We watched him waste away, down to skin and bone. Just an ash-colored shadow of the strong, handsome, complicated man I loved.

And still cherish, to this day.

Authors Notes:

This story is about a real man. Not a saint, not a hero from some bullshit movie. A walking, talking, drinking contradiction. The kind of man they don’t make anymore.

You want to understand him? You have to understand the slaughterhouse. A man who could use his strength to calm a half-ton beast right before another man smashed its skull in with a sledgehammer. That’s a man who understands how the world really works. It’s gentle, and then it’s brutal, all in the same damn breath. He lived his whole life in that one moment.

And then you see how the world repays a man like that for a lifetime of hard labor. It ruins his hands. The government he worked for sends him a mailbox full of pills that turn his brain to mush until he’s dyeing his hair with a Sharpie and can’t tell the brake from the goddamn clutch. They take a strong man and they just… dismantle him, piece by piece.

But what he gave you, that’s the real story. He didn’t give you a perfect example. He gave you The Benny Hill Show and cynical, gutter-level wisdom about women. He taught you how to find treasure in a dumpster. He taught you the ugly, beautiful, honest truth about being a man in a world that’s always trying to kill you.

And that ending… Christ. Finding out you were born in the same goddamn building where he died? That’s not just a coincidence. That’s poetry. The universe telling you the whole damn thing is just a perfect, rotten circle. You come in one door, you go out another down the hall. And all you can hope for is that in between, you lived a life as real as his.