My mother had left us again, my little brother and me, for another night of chasing whatever it is a lonely, drunk woman chases in a town full of potental step fathers. We were bored, me and a couple of other neighborhood kids, and boredom in a place like that is a dangerous thing. It’s a kind of sickness, a quiet, creeping rot that starts in your gut and works its way up.

So we did what bored animals do. We went hunting for weapons in my dad’s garage.

Mike came out with an emergency brake handle from an old Volkswagen, a good, solid piece of German engineering. Kevin found the handle of a car jack, simple and brutal. And I found the prize: a Braveheart-style meat tenderizer, the kind with the spikes on it, the kind you use on a tough piece of meat. We dressed in dark clothes, smeared some of my old man’s war paint on our faces, and we went out into the quiet, sleeping neighborhood. We weren’t sure what we were hunting for. But we knew we’d know it when we saw it.

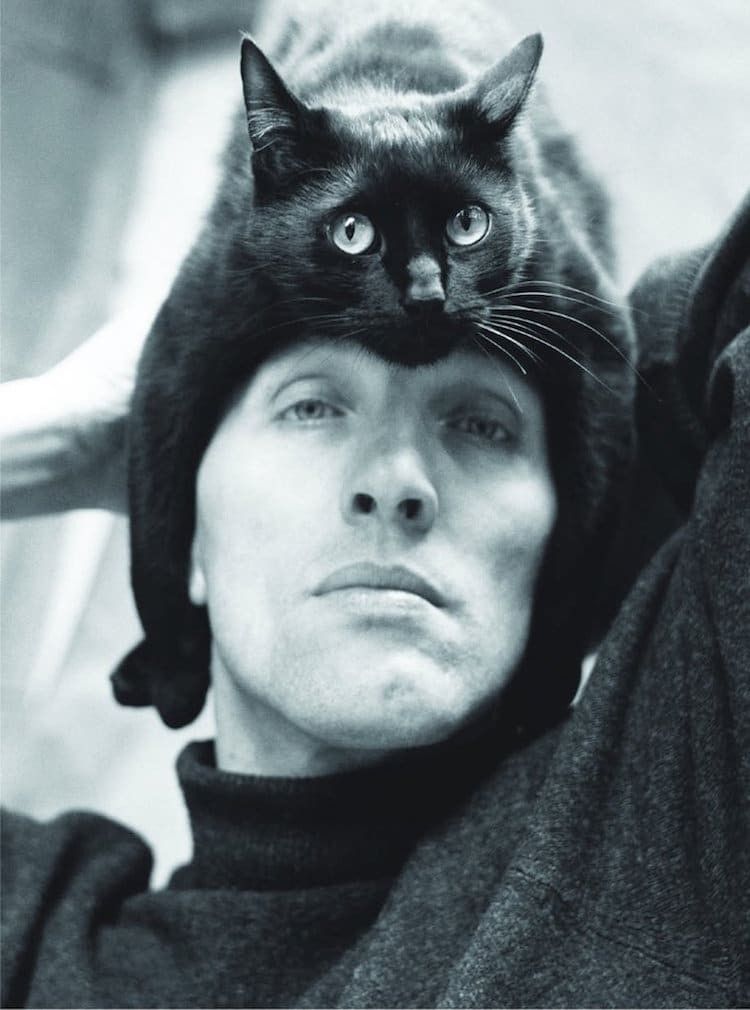

We walked the block, sticking to the dark spots between the streetlights where the good, decent people didn’t bother to shine a light. We saw a cat, but it was too smart, too wild. It wouldn’t come close. Kevin threw a rock at it, but it was already gone. Then a stray dog, but it just looked at us with a kind of sad, weary understanding, like it could smell the secondhand desperation coming off of us in waves.

It was getting late. One last big loop before I had to go back to the house, clean up the mess, and unlock my baby brother from the cage they called a crib. The night was quiet, uneventful. And then, right as we were about to give up, the perfect little sacrifice came running right towards me, meowing its goddamn head off.

The owner’s front door was open, the blue light of a television flickering inside, the sound of some stupid sitcom blurring out into the night. The three of us just stood there, frozen, like we’d stumbled onto a holy site. And this little cat, this perfect, trusting little fool, it came right up to me.

I didn’t think. I just acted. I had the meat tenderizer in my hand, the one with the little metal spikes on it. I swung it, a clean, simple arc. The poor little thing went flipping up into the air, spun twice, and then landed with a soft, wet thump on the sidewalk. And then it started to shake. A violent, rhythmic twitching that broke the quiet of the night.

We all ran.

We waited, hiding in the shadows, but no one came out of the house. No one responded. I snuck back up to it, keeping one eye on the screen door of the owner’s house. I grabbed it by the tail and dragged its still-twitching body around the corner, into the dark. We giggled like little girls, the three of us, standing over this small, broken thing. What do you do with a sacrifice once you’ve made it?

You have to understand, we were all from broken homes. Greg’s mom and dad were at war. Mike’s were separated. Mine were long divorced. This was our urban version of a tribal ritual. A white-boy thing, maybe. The quiet, bored beginnings of an ax murderer. But for us, in that moment, it was just… normal.

We looked at the beautiful little cat, its body finally lifeless. No one wanted to do anything. So I grabbed its tail again and started to spin, faster and faster, like some goddamn Greek Olympian about to throw the discus. I could hear the little bones in its tail crackling and popping, like a chiropractor making an adjustment. And when I felt the last one give, I let it go. It went flying out into the middle of the street, spinning like a furry, dead frisbee.

And with that, we all ran again, squealing and giggling like the stupid, fucked-up little kids we were.

Greg went home to his mommy and daddy. Mike went back to his father’s house. And I went back to my own quiet, empty home. I checked on my brother, still lying on his back in the crib, a future flat-head in the making. I cleaned up a few things, and then I sat down to watch Johnny Carson. Then the headlights swept across the living room window.

I quickly turned everything off, ran to my room, stripped down, and pretended to be asleep. Normal practice. Standard operating procedure.

A minute later, my mom comes crashing into the house, drunk off her ass, a maniac in a housecoat. She flips on the light in my room, and she’s already testifying, telling me the great, tragic story of her night. She’d run over a little cat, she said. It was just lying in the middle of the road. She’d hit it. She felt so awful, she said. She’d even pulled over to look at it, to confirm that it had passed away. “Oh my God, Jimmy,” she cried, her voice thick with that phony, drunken drama. “I can’t believe it happened.”

She just needed a buddy to talk to, someone to absorb her bullshit before she passed out. She never even noticed that my brother had been locked in his crib for over twelve hours.

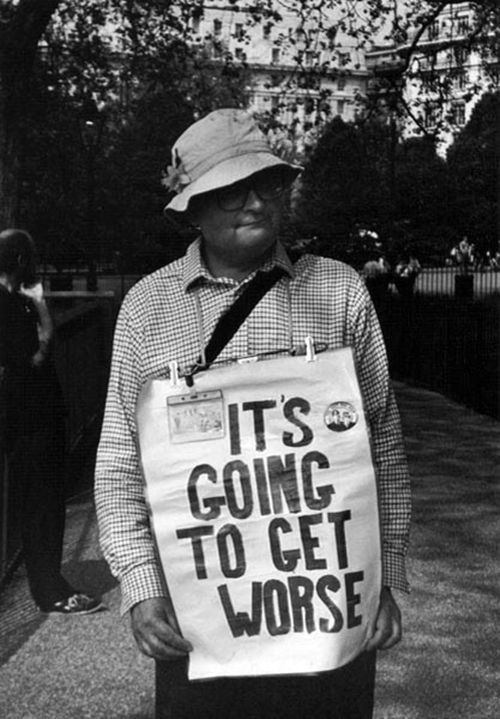

The universe has its own unique, sick sense of humor, doesn’t it?

I told the boys the next day. We all laughed our heads off. Sick? Maybe. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s just the dark humor you develop when you’re born into a world that’s already broken. The numbness of your soul that allows you to laugh at it all, because if you didn’t, you’d just start screaming and never stop.