There was a knock on the door one night, and there they were. Six of them. Mormon boys in their clean white shirts and their sad, hopeful eyes. Brother Olsen, Brother Caldwell, Brother Nelson, and a few other fresh-faced kids who hadn’t been ruined by the world yet. I had a party going on, the kind of quiet, desperate party you have when you’re married and miserable.

“Bad timing,” I told them. “Wrong house, wrong life.”

Brother Olsen, he just held up a VHS tape. “Family Is Forever.” The same one I’d asked for at the temple, the same one I’d called about after seeing one of their commercials late at night, drunk and lonely.

“Let’s try another time,” I said.

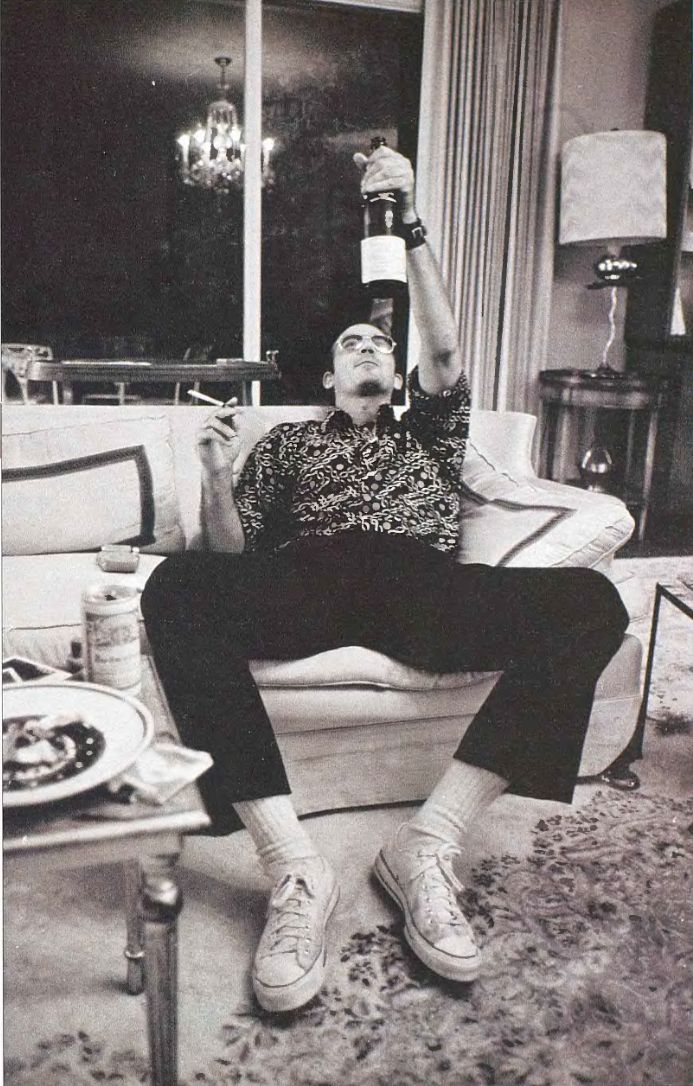

And they did. They came back a few weeks later. My wife—the one who was still normal then, before the crazy got her—she sat on the couch with me. I had a Jim Beam and Coke in my hand, as usual. We went through a couple of their lessons. I wasn’t really interested in the religion, but I liked the stories. I liked the energy of the boys. They had this smile, this clean, simple, Gomer Pyle kind of outlook on life. Childlike.

We stopped with the formal lessons after a while. They’d just come over, and I’d tell them jokes. I was funnier back then, especially after a few drinks. We did this for a couple of months.

Then one weekend, my wife and I, we drove up to L.A. to see my family. Our car broke down, of course. We had to take a bus. We were sitting around with my family, and we mentioned we’d been talking to the Mormons. My uncle’s wife, Pam, she jumps right in. “You know they believe in a different Jesus,” she says, “and they wear funny underwear.”

I didn’t know. But it sounded interesting.

We got back to San Diego, and the boys came over. They noticed I didn’t have a drink in my hand.

“Do you guys wear funny underwear?” I asked them.

“No,” Brother Olsen said, with a straight face. “We do not wear funny underwear.”

“Okay,” I said. “Then do you believe in a different Jesus?”

“No,” he said. “Jesus is the same Jesus from the King James Bible. There’s no different Jesus.”

I was satisfied. Then the kid, he leans in, looks over at the top of the fridge where all my liquor bottles used to be. “What’s going on?” he asks.

“Oh,” I said, “I was just trying to be respectful. I didn’t want to be drinking in front of you guys if it made you uncomfortable.”

And that was his cue. He launched into their lesson on the “Word of Wisdom.” When he was done, he looked me right in the eye. “Will you accept the Word of Wisdom and stop drinking?” he asked.

And without a second’s hesitation, I said yes.

Just like that. I was drinking a 750ml bottle of Jim Beam every single day, if not more. My poor, beautiful wife, before the crazy got her, she was suffering. I was miserable, working in the shipyards, and I didn’t know how to vent. So I stopped. Cold turkey. For nine years.

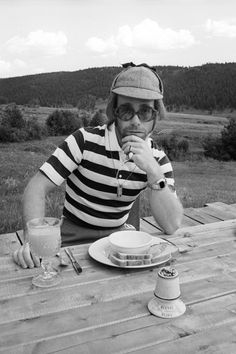

The boys finished their lessons and invited us to church. We went. The bishop, a guy named Davis, he was no older than I was, but he had something… different. An aura. The whole ward, it was full of these beautiful, powerful people who just seemed to glow.

There was this scripture I liked: “Without works, faith is dead.” To me, that meant you had to do something. You had to be a good man. You couldn’t just give it lip service, like all the other Christians. And the idea of the Trinity, of Jesus on the cross talking to himself, that always seemed like a load of bullshit to me. The Mormons, they had three individual gods, working as one. That made more sense.

But the thing that really hooked me, the part that felt true in a way I didn’t want to admit? It was the Mark of Cain. The story of the Lamanites versus the Nephites. The dark-skinned versus the light-skinned. I was going through a hard time with that myself. The gays were pushing the blacks out of Hillcrest and into my neighborhood. My garage was getting broken into, my car was getting vandalized. The ambassadorship of this particular group of people was shit. And it was easy, in my anger, to believe that the Mark of Cain was real. Joining the Mormon church, it was as close as I could get to joining the Klan without having to buy a goddamn sheet. A group of all-white, happy people, living in a clean, safe, and completely segregated bubble. They returned their shopping carts. They knew the code of etiquette. You could trust your wife with these people.

A few months later, I was in a meeting with the Elder’s Quorum. They asked me if I’d accept a calling, a position in the church.

“I can’t,” I told them. “I’m not a member.”

They looked at me like I’d just grown a second head. My wife and I, we were the goddamn poster children for Mormonism. Barbie and Ken. Good-looking, clean-living. They just assumed we were already in the club.

So they asked me if I’d be baptized.

That Sunday, Bishop Davis gets up in front of the whole congregation. “We have some new members being baptized tonight,” he said, his voice cracking, tears in his eyes. “You probably all know them.” He gestured to us, and the whole goddamn room turned around and gasped. They all thought we were already one of them.

That night, the place was packed. Everyone was there. A friend of mine, Larry, a guy from the High Priesthood, he took me down into the baptismal font. We were both wearing white. He said the prayer, and he dunked me.

I came up out of the water, and Bishop Davis and Larry, they laid their hands on my head and gave me the Priesthood. And with that power, I was able to baptize my own wife, right there in front of her father and her own nutcase mother, the same woman she would later turn into. It was an incredible moment, being the center of attention, being elevated like that. It was a beautiful, and completely unreal, time.

Now that we were official, we got our callings, our jobs in the church. Eventually, I baptized my own father-in-law and mother-in-law, probably the best thing that ever happened to them. I didn’t get to see it for long, but in the short time I did, I saw a change in her. The negativity, the toxic bullshit, it just… stopped. No coffee, no booze. It was a good thing.

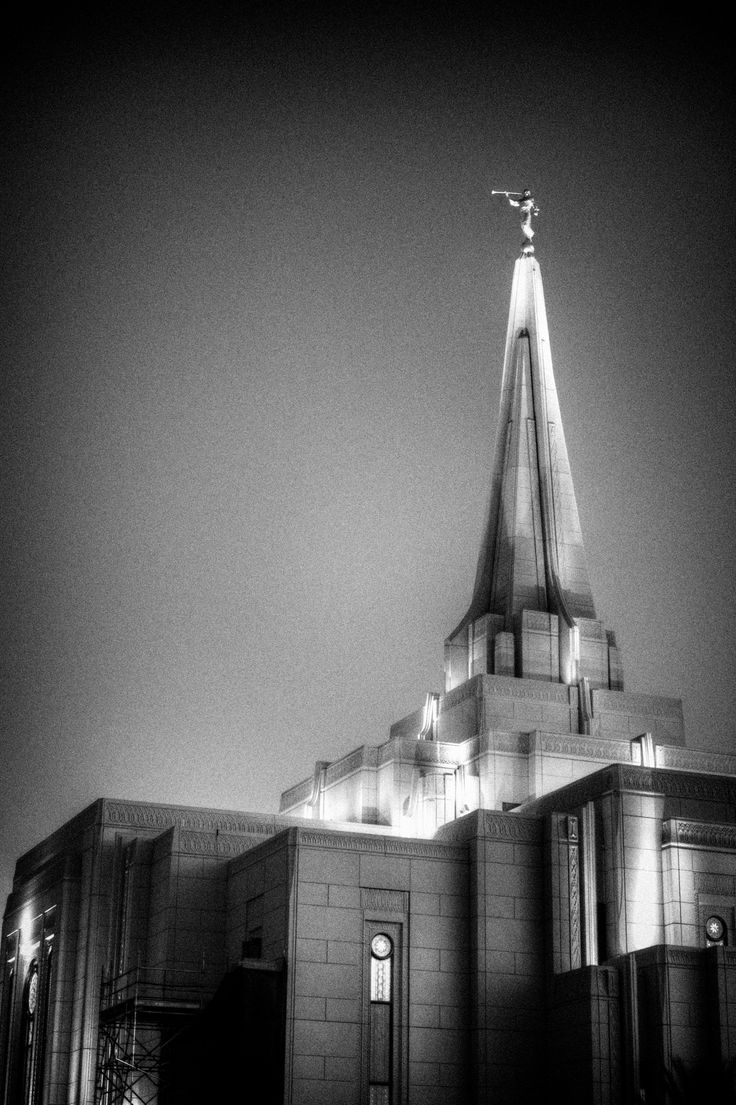

Then we were asked to go to the temple, to do baptisms for the dead. This was it. The temple was what got us excited in the first place. I remember going in, and the energy, it was different. I just floated through the chambers, changed into my white clothes.

I glided from the locker room to the waiting area, and there she was, my beautiful wife, before the crazy got her. I sat down next to her.

“Oh my God,” she whispered, her eyes wide. “It’s true.”

I was in a daze, just staring at the golden oxen holding up the baptismal font, the whole divine godhood of the place.

“No,” she said, “not the church. The funny underwear. They wear funny underwear. I saw it.” She’d asked Larry’s wife, who had told her they weren’t underwear; they were “garments.”

And that’s why Brother Olsen had been so precise. They don’t wear funny underwear.

They wear funny garments. And it’s true.