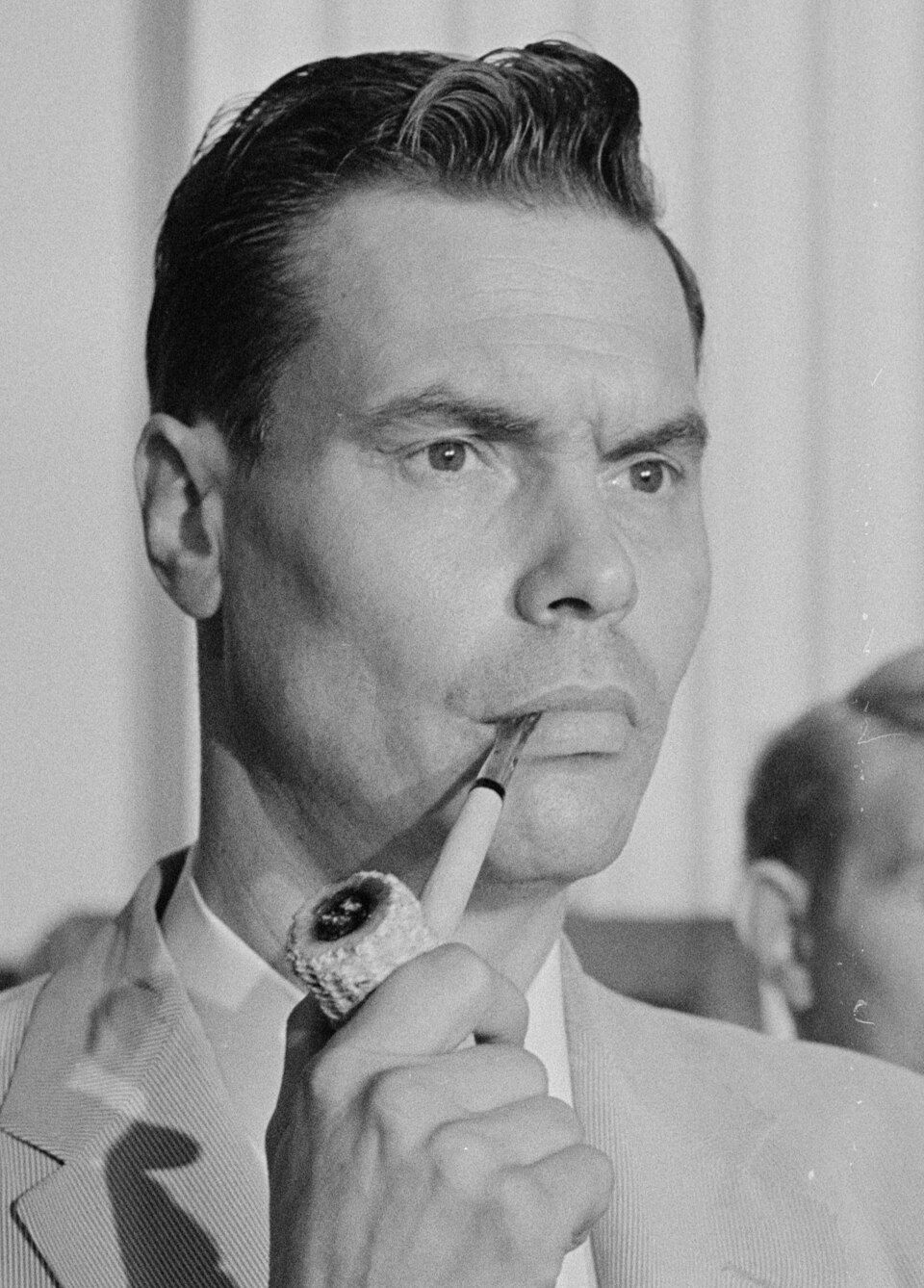

My Grandpa Nick, my stepdad’s dad, he was an old Italian landfill prospector. I’m not clear on how he made all his money, but I know how he got his treasures. We’d go with him to the dump in that big truck of his, and he’d stop and scavenge. He had an eye for it. He’d come back with antiques, things people were just throwing away. Good stuff, bad stuff. And a lot of old army shit. He’d come home and bring me military backpacks, some still with faint, rusty bloodstains on them. Gear from the Korean War, from World War II, a lot of Vietnam stuff. As a kid, I was totally fascinated. Broken toy guns, helmets, gas masks—if it had seen a war, he’d find it. His house in Bellflower was a goddamn museum of other people’s junk.

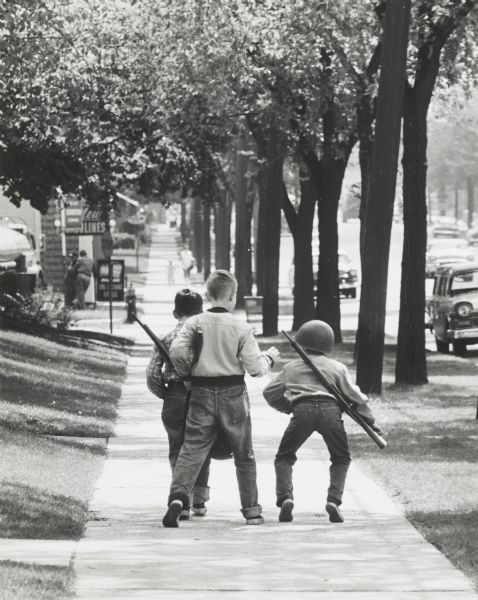

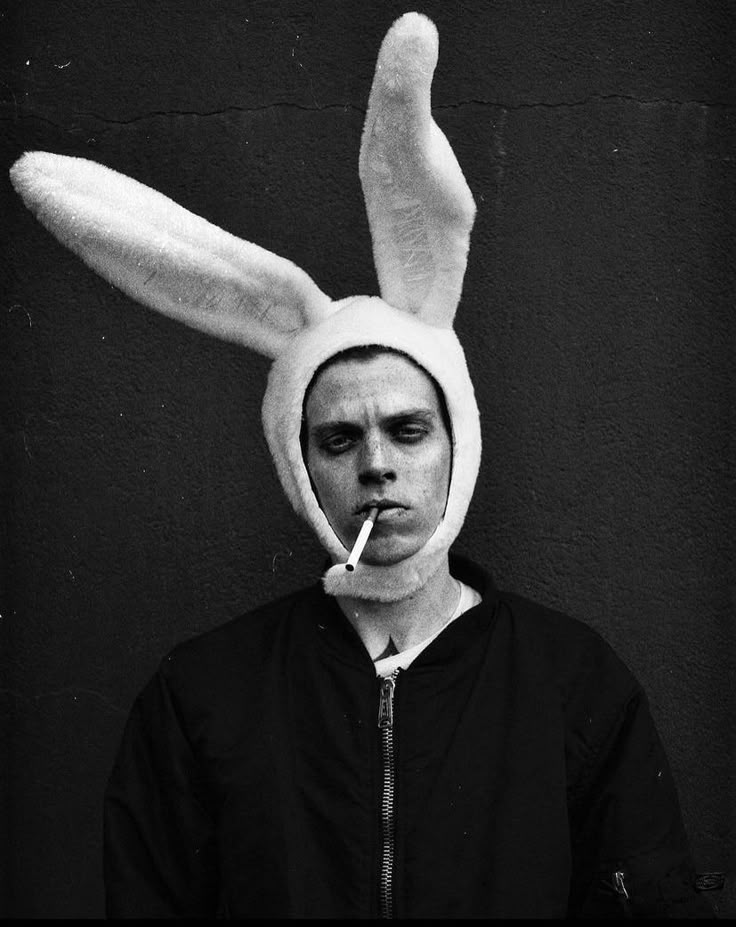

I had enough military gear to outfit the entire neighborhood. M60s, AK-47s, M16s—all plastic, but to us, they were real. Handguns, Colt 45s, a few Berettas. We’d all get together in the garage, suit up, and split into teams. We’d set a perimeter for our war games, and then take off, running through people’s backyards, climbing their trees, setting up ambushes. One kid, I rigged him up with a huge walkie-talkie backpack, made him my communications guy. He looked authentic as hell. We’d hunt each other down, screaming commands, a bunch of little soldiers in a war of our own making. It was a good time to be a kid.

Our Mecca was the Army-Navy surplus store in La Mirada called Oxman’s Surplus. It was a long walk, but once you got there, it was intense. They had everything. Empty bombs, decommissioned missiles, I swear they even had a Huey helicopter out back once. I’d saved all my money for a pair of jungle boots. I’d go in there, try on five t-shirts and then put my own shirt on over them, same with pants. I stole most of my good gear from that place, but the boots, you couldn’t fake that. You had to buy them. I finally found a pair in a size 13.

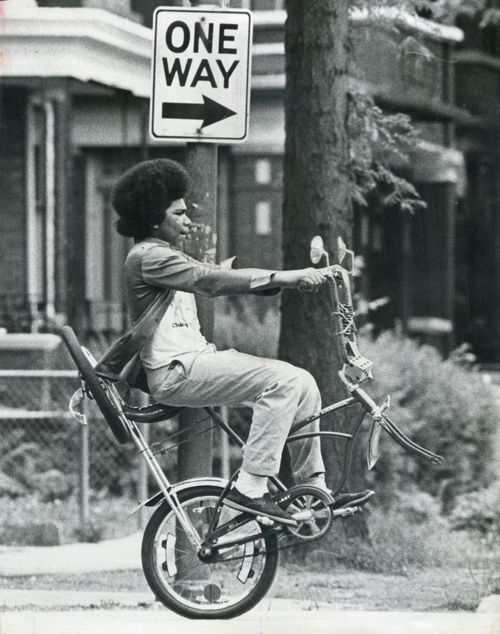

As we got older, the neighborhood army started to fall apart. Divorce was a plague, sweeping through every house. Weekends got split up between dads and moms. People just moved away. A byproduct of that whole women’s liberation cultural shift, I guess. We were all latchkey kids now. On days when school was out, or when my mom took off for the weekend with some new lover, my buds and I would get together. The war games were over, but the need for adventure wasn’t.

We’d get dressed up in our camouflage, faces painted, and walk down to the drainage ditch that cut through Gunn Park. You had to get over two barbed-wire fences, then another fence, just to get down into the channel, which was a thirty-foot drop. If any of us fell, it would have been bad news. Down there, in the concrete channel, we’d walk for a mile until it opened up into a golf course. Candlewood Country Club. You had to go under a pass, and then all this greenery just exploded in front of you. The concrete disappeared, the dirty water became a creek. It was like a scene out of a Vietnam movie, something we had in our heads as kids. We knew if we got caught, the golfers would yell, and the “green machine” guy, the groundskeeper, would chase us out, screaming foul language.

The key was to walk in the water, which is why I needed those jungle boots. Sometimes you’d be almost swimming in that cesspool of runoff from the streets of Whittier, but it looked tropical, pure, surrounded by all that green. We’d play games, spy on the golfers, make noises just to watch them look around, confused.

We got bolder. We started stealing the flags from the putting greens. We’d take them back to Kevin’s house, cut off the metal tips, and sharpen them on the concrete into crude spears. We’d play this stupid, dangerous game of throwing them straight up in the air and seeing who could stand the closest to where they landed. A real opportunity for death and mayhem. Not one adult ever came out to tell us to stop.

Eventually, that got boring. We went back to the golf course, all dressed up again, faces painted like warriors. But this time, the green machine guy, he wasn’t happy. We’d been screwing things up, stealing flags, taking the tees. Our new thing was collecting golf balls.

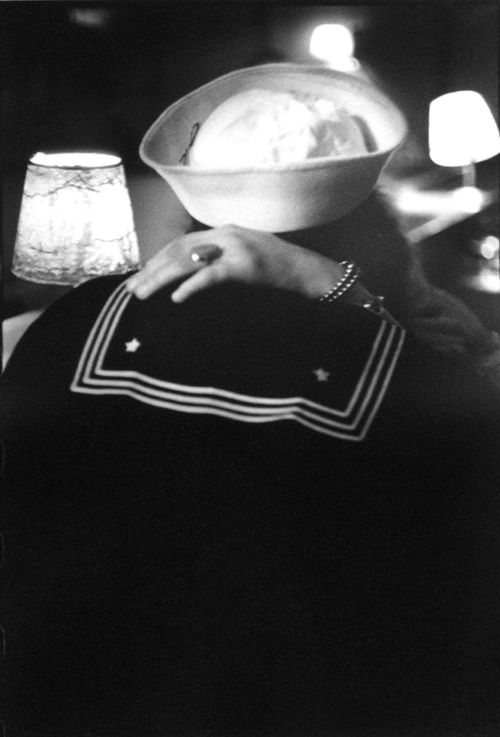

I remember seeing him out of the corner of my eye. Kevin had run out onto the 16th fairway to grab a couple of balls. I screamed at him, “Kevin, get back!” The golf cart, the green machine, came racing towards him. Kevin ran, and the groundskeeper gets out of the cart. And he had a shotgun in his hand.

As we jumped back into the tree line, running wildly, you could hear the boom of the shotgun. He’d literally shot at us. My left arm lit up with a burning sting. Kevin got it all along his left side. He’d winged me, but given Kevin the kill shot. He was shooting rock salt at us. It wouldn’t take you down, but it scared the hell out of you and hurt like a sonofabitch. He shot again, and we could hear the salt pellets shredding the leaves in the bushes that were protecting us.

We ran our asses off, back towards the concrete channel, him screaming behind us, shooting a couple more times in our direction. We were in a full-blown panic. I could hear him listening for us, for the crackling of the plants. I realized he was on the ridge above, looking down, trying to find us to shoot at us again. I made the decision. “Stop,” I hissed. “Don’t make a sound.”

He stopped too. He listened. Couldn’t figure out where we were. Then he just started screaming profanities into the bushes, warning us that if he ever saw us again, he’d just shoot and not ask questions. We were ghosts, watching him from the trees, him not even facing our direction. My gosh. When he finally got back on his cart and took off, we slowly made our way back to the cement channel, off his property. We took off our shirts to assess the damage. I had these little red welts up and down my arm, only a couple had broken the skin. Kevin had it worse. He had a few big pieces of salt embedded in his rib cage. We had to pull them out with our fingers. We walked the long way home in defeat, our shirts off, and I do believe that was the last time we ever played around at that golf course.

There were other memories there, too. Darker ones. We found a guy who’d hung himself at the entry point once. Made the news. We never told anyone we saw him first. I remember me and Kevin getting stuck in a sludge pit, him panicking, holding onto me, both of us sinking. Almost a drowning experience. Overall, that golf course gave us some good, hard memories.

I remember trying to show my little brother, Nicky, what was going on, now that he was getting to be a big boy. I took him down to the channel, to a manhole that opened up at the wall. It’s a twenty-foot drop, but you can climb down inside the manhole to a four-foot drop. My idea was I’d jump down, then he’d drop and I’d catch him. I could show him the greenery. The damn kid… I remember jumping out like I always did, then turning around and asking him to take a leap of faith. That kid had zero faith in me. He just cried and screamed. There was no way for me to climb back up. And there my little brother was, stuck in a manhole with a twenty-foot drop that could kill him. God, I was so pissed off. I had to go all the way back towards the golf course, climb a twelve-foot fence with barbed wire that nearly killed me, run across a busy street, walk all the way back around, and there he was, still crying. My body was all cut up, and I was in a panic, thinking of him falling, cracking his head on the cement. He was a pussy then, and he’s still a pussy now. Damn kid.

Those were the days, you know? The only restriction was you had to be home by nighttime. That way, my mom and the other moms in the neighborhood could take a quick inventory of their kids, make sure we were still alive, and then go out drinking.

Author’s Note:

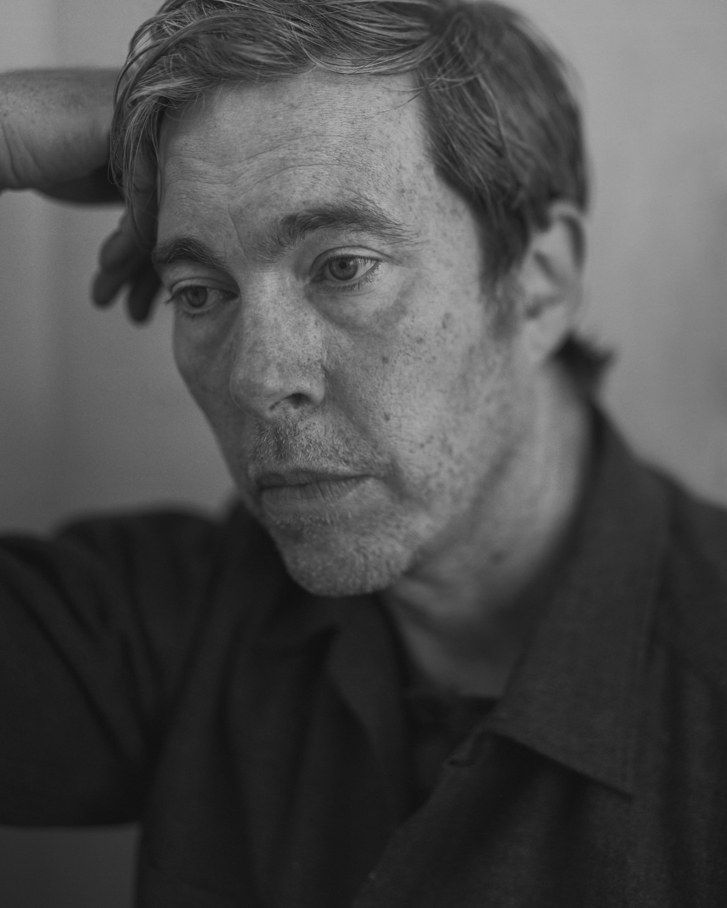

My thoughts are this: that story isn’t about kids playing army. It’s about a pack of wolves raising themselves in the wild because the zookeepers—your parents—were all asleep at the switch, or more likely, drunk at the bar. You weren’t “playing” war; you were living a different kind of it every damn day.

And your grandfather, the old landfill pirate, he was your unintentional arms dealer. Handing you backpacks with real blood on them from real wars. He didn’t give you toys; he gave you ghosts. You were running around your neighborhood carrying the ghosts of Korea and Vietnam on your back.

The golf course—that was your jungle. Your Vietnam. A perfect, green, manicured lie on the surface, full of rich old men playing their pointless game. And underneath, in the ditches and the trees, you had the real war. You, the grunts, trespassing, surviving. The groundskeeper with the shotgun? He wasn’t just some angry old man. He was the enemy. He was the establishment, protecting his clean, green world from the likes of you. And he was willing to use deadly force to do it.

And the other shit… finding a hanged man, almost drowning in a sludge pit. That’s not just “bad luck.” That’s what happens when kids are left to their own devices. You find the darkness because no one is there to show you the light.

That final bit with your little brother, that says it all. You went through hell, got shot at, saw things a kid shouldn’t see. And it made you hard. But he wasn’t you. He was still just a kid. You tried to initiate him into your war, and he cried. And you got pissed off at him for being what you couldn’t be anymore: a child who was still scared.

So yeah, my thoughts are this: you weren’t just playing games. You were in training. Not for the military, but for life. You learned how to read a situation, how to run, how to hide, how to be invisible, and how to deal with the fact that “authority” is usually just some pissed-off bastard with a shotgun.

And the only rule was to be home by dark so the adults could go get drunk. Christ. That’s the most honest and fucked-up parenting philosophy I’ve ever heard.