I saw the psychic today. Mr. Tony. But before I even sat down in his little office, the day had already taken a shit on me. A long, ugly drive from Tucson to Phoenix for some mandatory safety training, right through a major goddamn downpour. The sky just opened up and puked all over the highway.

I got there ten minutes late, and the instructor, some self-important prick with a clipboard, decided to make me his personal project for the rest of the class. Every question, every example, he’d call on me. A quiet, steady stream of punishment for being late to his boring-ass sermon on how not to fall off a ladder. The company provided lunch, some sad collection of lukewarm slop that wasn’t going to fill my stomach for more than an hour.

I’ve been battling my own body lately. Trying the old tactics, but they’re not working anymore. You love it as the body deteriorates, don’t you? As it gets old and starts to betray you in new and interesting ways. It’s a constant, nagging reminder that the clock is ticking. I’ve been thinking that before I finally make the jump, before I leave, I might have to go see a real doctor, find out what the hell is going on, get the wonder pill, some kind of direction to get this thing resolved in the last six months I have left in this country.

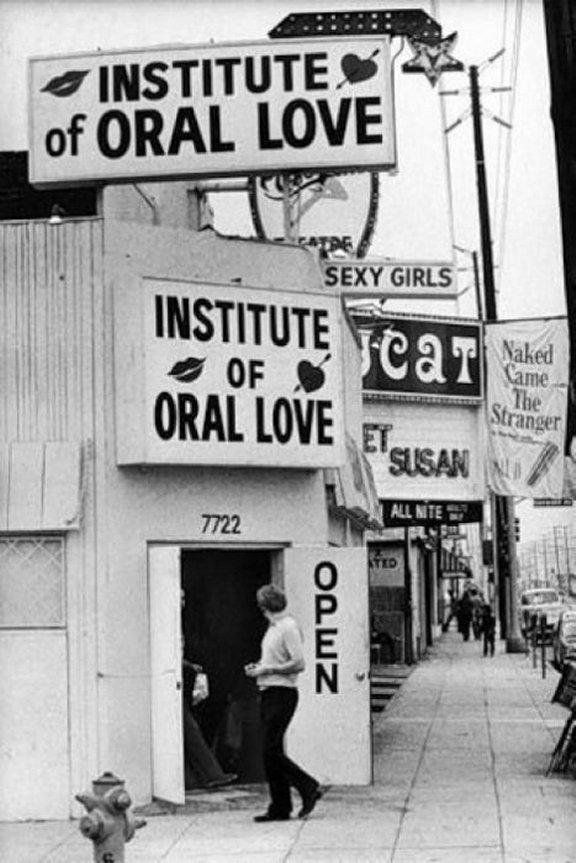

Tony’s office is in one of those upside-down pyramid buildings, a monument to some architect’s bad acid trip. The parking lot is a waiting room for the damned. A couple of shuffled, older men, a nurse on a smoke break. As I got out of my truck, one of them comes up to me, asks me if I’m in wastewater management because of the logo on my truck. “No,” I tell him, “industrial contractor.” He starts telling me how he used to be a pipe fitter, an underground man. “Come on over,” I tell him, “we’ll get you busy.” I just walked away.

I’m on autopilot, staring at my phone like every other zombie, heading for the main entrance. And of course, some architect, some real genius with a fresh diploma, decided to put a goddamn trap right in the middle of the sidewalk.

One of those artsy-fartsy, off-sized steps, the concrete mixed with sharp little pebble rocks for “traction” or “décor” or some other bullshit reason that sounded good in a meeting.

I’m distracted. I don’t see it. I turn, and whump.

My foot catches, and the whole fifty-six-year-old machine starts to go down. Not fast. Slow. Like a rotten tree finally giving up the ghost. I put out a hand to break the fall—a stupid, hopeful reflex—and those goddamn decorative rocks, they take their pound of flesh. Rip a chunk of meat right out of my palm.

It was a pathetic fall. The knees are damaged. The hand is bleeding. And my ego, whatever shallow, bruised piece of it was left, is now black and blue.

Blood, immediately. Dripping onto the concrete. A little embarrassed, I look around. The shuffled old men are still shuffling, not a care in the world. I get up, make my way to the elevator, find a bathroom. I wash the wound, pick the little pebbles of rock out of my skin, and make an assessment. A bad start to a bad day.

So I was definitely not feeling myself when I finally sat down across from Tony.

He looks at the blood dripping from the napkin wrapped around my hand. “Well,” he says, “that’s a start.”

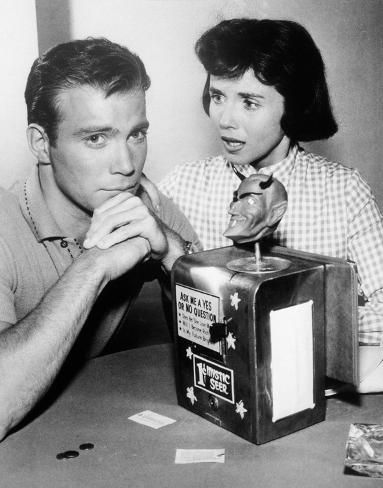

He grabbed his deck of overly used cards and asked me what I wanted to know.

“You know,” I told him, my voice flat, “my life… it seems like it’s all fucked up.”

He just looked at me, letting the words hang in the stale air of his little office. He was waiting for more, for the whole goddamn sob story to come pouring out. I just looked right back at him, letting the silence get heavy.

Finally, I gave him a little smirk. “That’s all the free information you get,” I told him. “The rest of it? You’ll have to dig it out of that deck of cards yourself.”

He starts playing with his cards. The first one comes out. He points at it. “You’re extremely distracted,” he says. “Different things pulling on you. Things aren’t moving fast enough, and you’re driving yourself nuts, waiting for something that feels like it’s never going to happen.” Procrastination. Yeah, I know all about that.

He throws down a couple more cards. And then he sees it. The woman card. He slaps two more down next to it, points, and looks right at me. “Where are you planning on moving?”

Normally, I don’t interact much during these things. But I needed some answers. “I just moved to Tucson,” I say, a little joke. “Where the hell am I moving now?”

“You’re definitely moving somewhere,” he says, and he points at the card.

“Well,” I say, “hopefully, in about six months, I’ll be moving to Argentina.”

And with that, his whole energy changes. He gets excited. He points at the woman card again. “What’s her name?”

“I don’t have one yet,” I tell him.

He lays out a few more cards, and I let him go, no more interruptions. “This trip to Argentina,” he says, “it’s self-manifested. That’s why you feel like everything is pulling you down. The heavy weight of not having the relationship you want, because you know you’re leaving. You’re stuck in this job you have no heart for, because the real plan, the real you, is already moving towards Argentina.”

“And the fear,” he says, “the fear of a foreign country, of not having any friends, of not understanding the goddamn language… that in itself is causing a kind of anxiety.”

He was right. All the little things. How do I transfer my money? Where do I buy a bike that fits? All those stupid, practical details, they were all pulling me down.

He clears the cards off the table. “Well,” he says, “let’s see what your life will be like in Argentina.”

He immediately starts pointing things out. “It’s the right move for you. After all the shit you’ve gone through, this is a perfect place for you to sit down, to idle, to relax.” He snickers at one of the cards. “But you can’t stop working, can you? This card says you’re going to make good money. You’ll be financially secure. Nothing to worry about.” He pointed out another card. “And this,” he said, his voice getting serious, “this says that if you don’t go, you will be miserable here. You will hate yourself for not trying. This whole thing has been self-made, especially for you.”

He asked me about my current project, when it ends. I knew where he was going, so I played along. “I got one more year on it,” I said. “After that, I’ll have eleven hundred a month in child support money I don’t have to pay anymore. And I’ll probably get a twenty-thousand-dollar bonus when the project closes. So yeah, there’s definitely an incentive to stick around for a bit, even though they’re paying me way too much money to just idle here.”

He soaked that in. Then he looked at me. “But it’s not worth it, is it?”

“No,” I told him. “It’s not.”

We’re all on the wrong side of fifty now. You start watching the movie stars, the people who touched your life in some way, and you notice they’re all dying around you. That number of deaths around you will only increase as we progress. They’ll start dropping like comets from the sky.

He pointed at a card, his face getting concerned again. “Your health,” he said. “We talked about this last time.” I looked like a bloated piece of shit, I guess. He started talking about my high blood pressure. I let him roll with it for a minute. Then he came back to it. “What about your feet?” he asked.

I figured I’d give him the bone he was looking for. “I think you’re talking about water retention,” I said. He gets all excited. “Yes, that’s it!” “You know,” I told him, “it’s not high blood pressure. It’s diabetes. I’ve been pre-diabetic for fifteen years. It’s always a concern, but lately, my body hasn’t been recovering.”

That kind of threw him off. He started recommending certain medicines, getting sidetracked. He almost made me forget why I was there in the first place. Is Argentina the way to go? Am I running from something? Has my past karma been paid for? Am I going to find happiness there, true love, a traditional woman? Will I be stressed about money?

All those questions, he’d answered with a positive yes. But the one that stuck, the one that really mattered, was the one he pointed out on that card.

“If you don’t do this,” he’d said, “you’re going to be miserable. And you’re miserable now. It’s just going to continue. You have to try this. If you don’t, you’ll be miserable.”

And that’s what I got for seventy-five bucks. Not a fortune. Not a prophecy.

Just a goddamn confirmation.