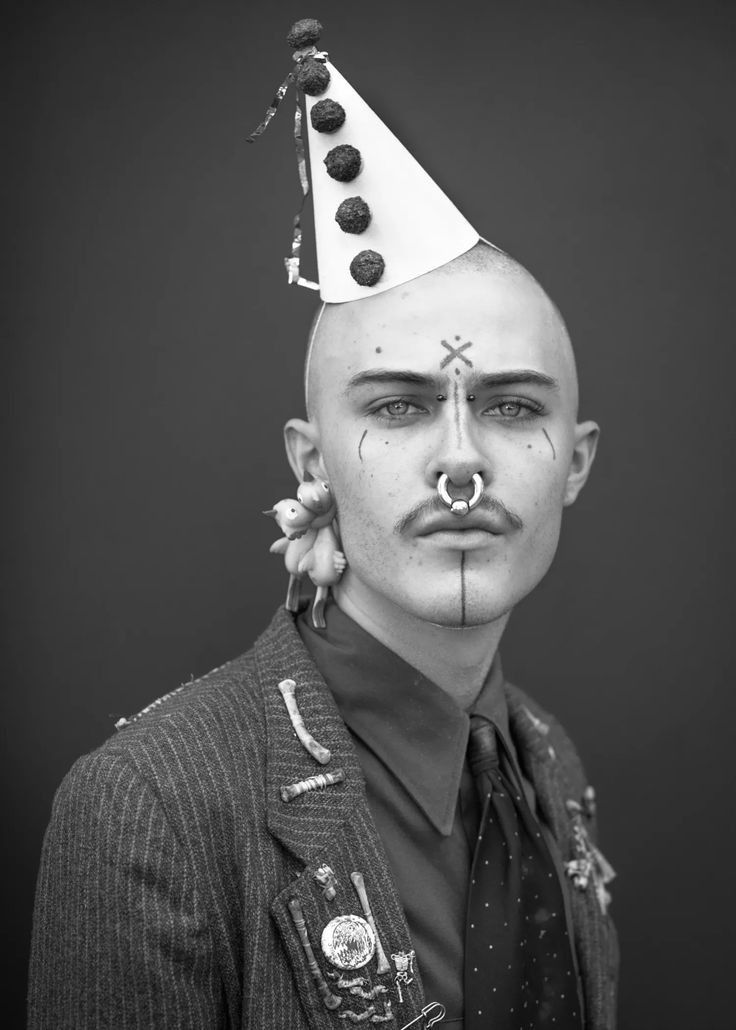

I was living on Dave’s floor at the time, or maybe it was the couch. It depended on how many empty beer cans were in the way. He’d “saved” me from some crazy bitch named Jackie who’d been holding me hostage down in Imperial Beach, which was just another way of saying he’d found a new pet. The deal was simple: I was his drinking buddy, his court jester, and his weekly alibi for his trips down to Tijuana. He’d sabotage his own boring relationship just so he could have a little “guy time” in some filthy Mexican cathouse, and I was the price of admission.

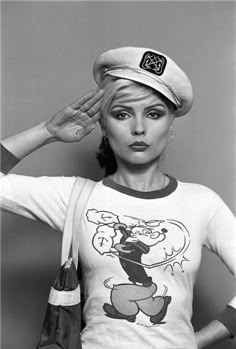

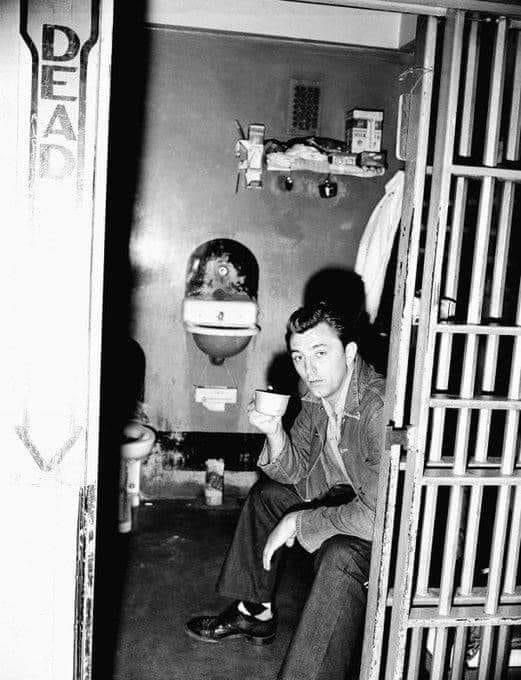

It was a good gig, for a week or two. But the welcome mat was getting worn thin. I didn’t have a job. I didn’t even know how to look for one. I’d been in the Navy, so I looked at navigation jobs, but they didn’t pay shit, and besides, I didn’t have a car. I was a nineteen-year-old kid, maybe twenty, with a Bad Conduct Discharge from the U.S. Navy and a rap sheet that was just getting started. I had no skills, other than being handsome and strong, and that was only getting me so far.

Dave finally got tired of looking at my ugly, hopeful face. He talked to his baby mama, and she gave me a phone number. A subcontractor, she said. Fiberglass. I didn’t even know if fiberglass had a smell, but the place sure as hell did. It smelled of quiet, industrial death. I filled out an application, and some tired-looking sonofabitch looked at my big, dumb, and completely useless body and said, “You’re hired.”

He handed me a hook knife and a roll of duct tape, put me on a bus with a bunch of other lost souls, and we drove down to the shipyards, right under the Coronado Bridge.

There was only one boat there, the USS Halsey, a big, gray, and completely unimpressive piece of floating steel. She was having some major repairs done, the crew still living aboard, the boilers still hot. Our job, for the next few months, was to crawl into the guts of that beast and rip out all the asbestos.

They sent us to a special “training,” a one-hour class in a stuffy trailer where they taught you how to die slowly. They told us that one single, invisible fiber of this shit could kill you. They fitted us for masks. The test was simple: they’d wave a little cotton ball soaked in banana oil under your nose. If you could smell the banana, you were going to die. A perfect, beautiful, and completely insane system.

We spent the first month just building the containment chambers, wrapping the catwalks in thick, white plastic, creating a series of airlocks and showers for the two hundred plus men who’d be working around the clock. We were building a goddamn cathedral to a poison.

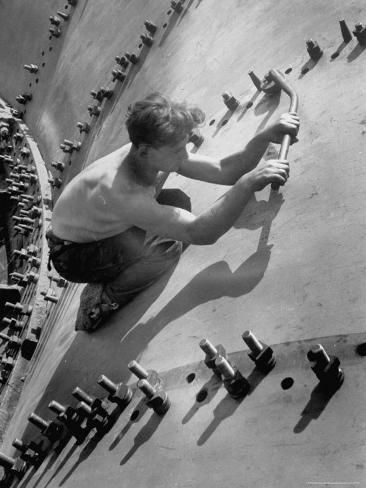

It was already a hundred degrees in the boiler room, the engines still running, and now we were supposed to put on these full-body bunny suits, tape our wrists and our ankles, put on gloves, and wear these positive-airflow masks with a long, clumsy hose that was always getting snagged on something. And then, we were supposed to go to work.

The job was simple: you’d take your hook knife, you’d jam it into a piece of pipe, you’d break the seal, and the asbestos would go flying everywhere, a beautiful, deadly snowstorm in the bowels of the ship. You’d rip it off in big, wet chunks and stuff it into a red bag with a skull and crossbones on it. And then, like ants, we’d move the bags, hand over hand, from the belly of the ship up to the deck.

It was draining. You’d work a ten, twelve-hour shift, and when you finally got to take the suit off, your whole body would just… deflate. A wet rag, puking out a gallon of sweat and cheap beer.

That was the first phase. The dirtiest work. When it was done, the crew of two hundred was suddenly down to a hundred. The next phase was the wire brushes. Still in the bunny suits, still in the heat, you’d just stand there, for twelve hours, brushing every single goddamn pipe until it was clean. Another two shifts of that, making five-fifty an hour, weekends too.

Then the crew shrunk again. The painters came in, a small, quiet crew of about thirty guys, spraying everything with a high-temp silver paint. We cleaned up, took down the plastic, and demobilized. And then, there were just a handful of us left. I was the guy with the air monitor, walking around, making sure the poison was gone. Just doing paperwork. Out of two hundred men, I was one of the last two guys on the boat.

And then I saw them.

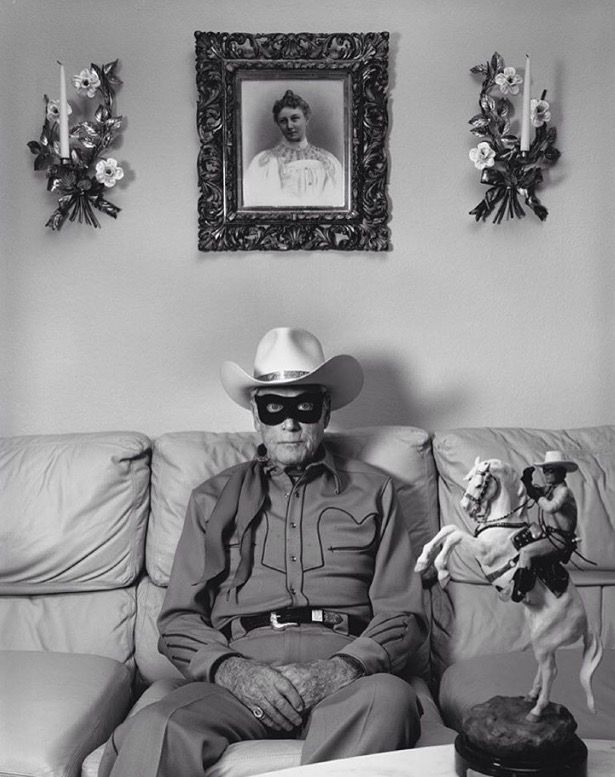

They came walking up the gangplank like they owned the goddamn world. They had on green hard hats and these canvas bags slung over their shoulders, with tools hanging off them like a gunslinger’s rig. They were from a company called Continental Maritime, and they looked like a bunch of beautiful, arrogant bastards. They were the insulators. The artists. They were here to put the new skin on the beast we’d just stripped bare.

They asked me if I wanted a job. “Yes, sir,” I said. They offered me eleven dollars an hour.

The first thing they had me do was “ragging.” Some old-timer was on a chiller unit, fitting these beautiful, black pieces of rubber insulation around the pipes. It looked like a goddamn sculpture. I remembered ripping that same shit out a few months ago, and now, it looked like a work of art.

“I want you to rag this,” he said.

He showed me how. You’d take a roll of fiberglass cloth, cut it to size, and dip it in a five-gallon bucket of this thick, white paste called “air ball.” You’d run it through your fingers, making sure it was completely saturated, like you were building a cast for a broken arm. Then you’d wrap it, smooth and tight, around the new insulation.

He showed me a couple of times, and then he let me have at it. And I was good. I was a natural. When I was done, you couldn’t see a single seam. It looked like it had been born there. Everyone came over to look. “Look at this kid,” they said. “His first time.”

And just like that, I wasn’t a laborer anymore. I was the “rag boy.”

I ragged and ragged and ragged, until one day, the foreman, a big, ugly, and completely beautiful man named Watermelon, he came over to me. “How’d you like to learn how to cut?” he asked.

“Yes, sir,” I said.

And before I knew it, I was a journeyman. I had my own knife, my own measuring tape, my own canvas bag. I was one of them. The guys with the green hard hats, the ones whose shit didn’t stink. We were the artists, and nobody could do what we did.

I worked with those guys for a long time. They were my father figures, my uncles, my brothers. They taught me a trade. I made enough money to get my own place, to get Dave off my back. I think I even got married somewhere in there, but that’s a different story, another beautiful disaster for another night.

The point is, I learned something down there, in the guts of that ship, breathing in the poison and the sweat and the cheap, honest camaraderie of men who work with their hands.

I learned to never, ever say no to an opportunity.

Even if it looks like a one-way ticket to hell. Because sometimes, that’s the only goddamn train that’s leaving the station.