When I got the call that my dad had cancer, I didn’t hesitate. I didn’t check my schedule. I raced down to Whittier, not to save him—you can’t save a man from his own biology—but to witness him. I needed to see if the giant was still standing.

My dad and my brother Nick, they had a weird ecosystem. It was like a husband and wife where one party keeps secrets and the other pretends not to notice. Nick was a codependent bitch boy, orbiting my dad like a moon with no gravity of its own. It worked for them. But when I got there, the orbit had collapsed.

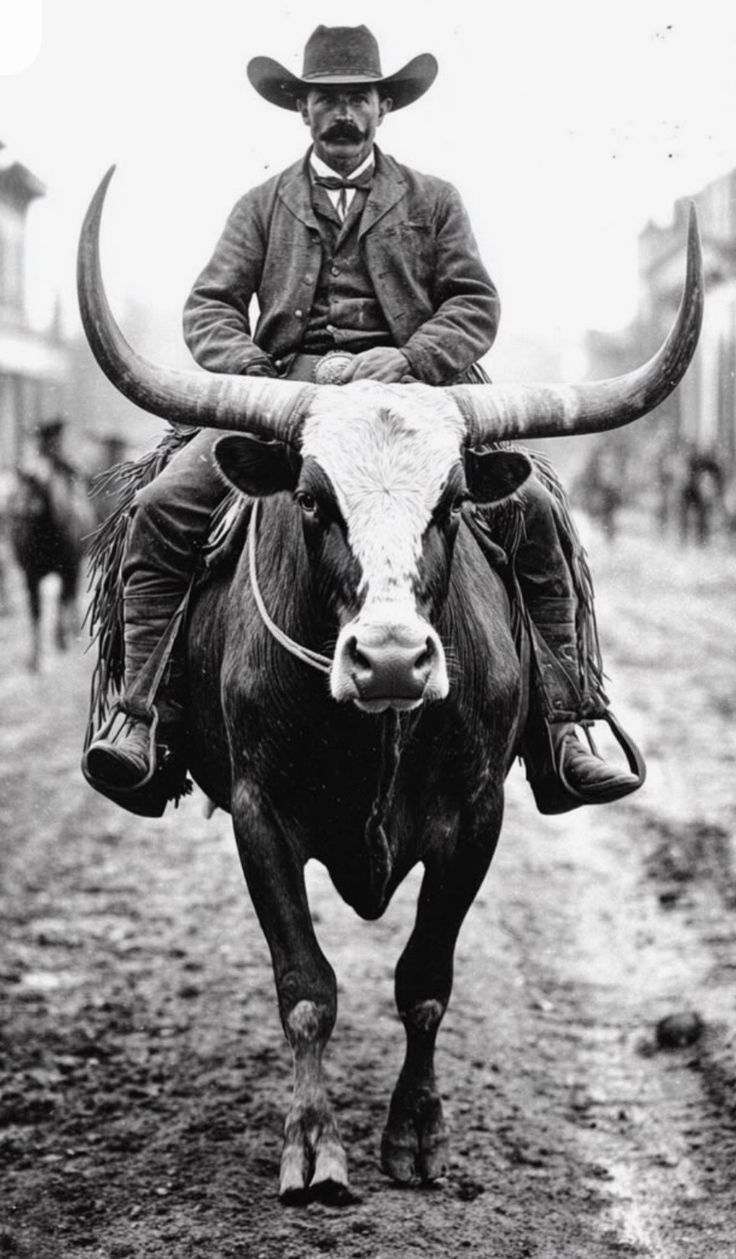

We went to the doctor’s office in Uptown. And I saw it immediately. The shift. My dad, usually a masculine, dominant force of nature—the man who waxed his truck on Sundays like he was polishing a holy relic—was smaller. The fight had been drained out of him before he even walked through the door. He looked like a dog that had just realized it had been abandoned at the shelter—confused, dull-eyed, and waiting for the end.

The doctor came in. Tall, pale, white-blond hair, blue eyes. Looked like he stepped out of a German military recruitment ad from 1940. He opened the file and started talking. Not about a cure. Not about winning. Just about stalling.

He talked about lymph nodes, radiation, chemotherapy. He talked about poisoning my father’s body in the hope of buying a few extra, miserable months. I flipped through a People magazine, half-listening, watching my dad stare at the floor. He wasn’t “Papa Bear” anymore. He was just a man in a paper gown, scared shitless.

I went with him. I sat beside him while the poison dripped into his veins. I was there when they tattooed the marks onto his skin, little black targets for the radiation beams. Just me and him. Through all of it.

And in those quiet, chemical-smelling waiting rooms, he started talking about the end. He knew.

“Jimmy,” he said, “you’ve always been the smart one. You handle this.”

The plan was simple. The house, fully paid for, split three ways. I’d get the high-end guns—the Brownings, the good shotguns from the ’60s. Nick would get the junk—the WWII relics with cracked stocks and rusted barrels. Ryan? No guns. He had a temper that could light a wet match, and Dad didn’t want to hand him a loaded mistake.

But I knew my brothers. I knew Nick had never seen that kind of money, and I knew Ryan needed something solid to help with his child support mess. So I suggested a trust. Keep the house, fix it up, rent it out, split the income. A legacy that keeps paying. A way to keep us connected, even if we hated each other.

Dad agreed. He seemed happy. Relieved. Like the weight of the world had shifted just an inch.

Then, when I handed him the trust papers to sign, he hesitated. The old fear kicked in. The hesitation of a man who spent thirty-five years asking for permission to mow his own lawn. “No, no, Jimmy. We’ll do this later. Not yet.”

Later never came.

A few weeks passed. The cancer spread like a brushfire in a drought. I rushed back down. He was in a coma, hooked up to machines that were just keeping the meat warm.

I sat next to him. I watched tears slip from his closed eyes. And I said “I love you” more times in that one night than I had in my entire life. Too manly to say it when he could hear it. Too desperate to stop saying it now that he couldn’t.

Nick and I had a falling out during that trip. Another drunken night, another brotherly disaster fueled by stress and cheap whiskey. Ryan was floating in and out, never fully present, never fully absent. When the time came to decide about pulling the plug, Nick stepped up, puffed out his chest like he was the man in charge. I was so disgusted I just waved him off.

“Fine,” I said. “Try not to fuck it up.”

I went back home to Oregon. I couldn’t watch the circus anymore.

And here is the tragedy. The goddamn punchline. Nick and Ryan took turns sitting by Dad’s bed. But Nick—the “company man”—had to get back to his ten-dollar-an-hour job because he was terrified of losing a paycheck. And Ryan—being Ryan—got hungry and left to grab a burger.

And while they were gone, Dad died.

Alone.

Not one of those stupid motherfuckers had the decency to stay with him, to hold his hand, to walk him to the gate. He died in a sterile room, by himself, surrounded by beeping machines and the silence of his own sons’ incompetence.

They handled the cremation without me. Didn’t even tell me.

A few weeks later, they went out on a boat to scatter his ashes. And because my family cannot do a single goddamn thing without turning it into a felony or a farce, my brothers got into a fistfight on the boat.

Ryan wanted the cars—Dad had eleven of them, mostly junkers, but to Ryan, they were gold. Nick wanted the control. So instead of mourning, instead of a moment of silence for the man who gave them life, they were throwing punches over his dead remains while the captain probably wondered if he should call the Coast Guard.

Then came the probate. The real war.

Nick, now firmly back in my mother’s pocket, dragged everything out. He squatted in the house, stalled the process, looted the bank account. He lived there rent-free, drinking Dad’s booze, eating Dad’s food, and burning through the cash. Ryan finally had to subpoena him just to get the ball rolling.

Ryan called me. I was knee-deep in my own divorce, fighting my own war in Oregon. “Sign whatever,” I told him. “I don’t want the drama.”

That sentence would come back to haunt me.

Months later, I’m drinking a grapefruit juice and vodka for breakfast—the breakfast of champions—sifting through the mail. And I see it. A thick envelope. The estate settlement.

I open it. I scan the names.

Beneficiaries: Ryan. Nick.

That’s it.

My name wasn’t there. I wasn’t just “left less.” I was erased.

I didn’t panic. I just picked up the phone. I called a lawyer in LA. “Dude,” he said, looking up the case number, “this hearing is in thirty minutes. I’ll be there.”

He stormed into the courthouse just as the gavel was about to come down. He stood up, interrupted the whole damn show, and laid it out: “Your Honor, the third son has been omitted.”

And then, like clockwork, my mother slithered to her feet.

She straightened her posture, put on that well-practiced, manipulative mask of the grieving widow (even though they’d been divorced for thirty years and she hated his guts), and declared to the court with a straight face:

“The adoption was never finalized. We just told him that so he wouldn’t feel bad.”

With one sentence, she tried to wipe me out of the family history. She tried to rewrite forty years of reality just to cut me out of a third of a house in Whittier. If I wasn’t legally his son, I wasn’t entitled to a goddamn dime.

My lawyer called me. “She’s hostile. She’s convincing. She’s making it sound airtight.”

“It’s a lie,” I said. “And it’s a stupid one.”

The court gave us 40 days. We dug up the birth certificate. Clear as day. My father’s last name. The adoption was final. No loopholes. We filed the paperwork, and the judge ruled in my favor.

My attorney was baffled. He’d watched my mother stand in open court and blatantly deny reality, claim documents were forged, lie with a straight face about her own son. “I’ve seen some shit,” he said, “but that was cold.”

In the end, the estate was split three ways. But there wasn’t much left. The probate fees bled it dry. The legal battles ate the scraps. And Nick—who hadn’t just been living there rent-free but looting the place like a tomb raider—had burned through whatever cash Dad had left.

Ryan messaged me later. “You told me you didn’t want any of this.”

“It wasn’t about the money,” I told him. “It was about the fact that you people made this a goddamn shitshow. It was about the principle.”

We never spoke again.

My dad raised three sons. He sacrificed everything. He took the hits. He never dated, never built a new life, never shut us out. He gave us everything he had, even when he had nothing left to give.

And in the end?

Ryan followed in our mother’s footsteps, swallowed by bitterness and bad decisions. Nick remained a needy, codependent wreck, forever looking for someone to latch onto.

And me? The adopted one? The one they tried to erase with a lie in a courtroom?

I carried more of my father in me than either of them ever would. I carried his work ethic. I carried his silence. I carried the memory of the fish pond and the Turtle Wax.

And that, my friends, is the only inheritance that the lawyers can’t touch.