Da Nang, Vietnam Sunday, February 8, 2026 | 9:39 AM

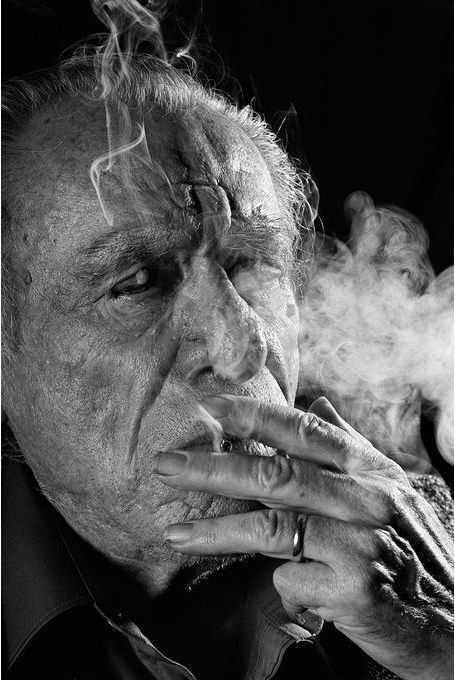

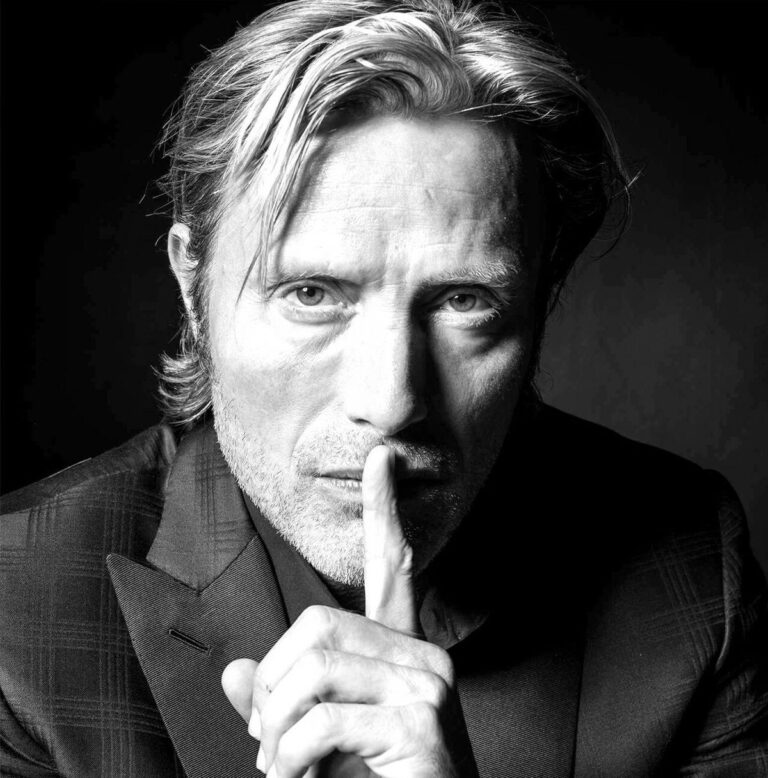

I sat in the plastic chair by the balcony door, watching the dust motes dance in the humid morning light. I was nursing a lukewarm Tiger Beer, wearing a linen suit that looked like I’d slept in it for three days—which, metaphorically speaking, I have.

You woke up slowly. You didn’t wake up with the gasp of a man remembering his debts or the panic of a man realizing he’s late for a meeting he hates. You just… woke up.

“Well,” I grunted, swirling the beer. “Look who decided to join the living.”

You sat up, rubbing the sleep out of your eyes, looking around the room like you were still surprised the walls were real. “I made it, Charles.”

“You made it,” I mocked softly, lighting a cigarette that didn’t exist. “You dragged your carcass across the Pacific Ocean, survived the ‘SIDS of Asia’ layover in Korea, and managed to smuggle fifty-seven years of trauma through customs without paying a tax. Congratulations.”

I stood up and walked over to the bed, leaning in close. I sniffed the air.

“I’m checking for the rot, James. I’m checking to see if the transplant failed. Usually, when a man your age rips his roots out of the soil and plants himself in a jungle, the organ rejects the host. He starts drinking. He starts crying about the ex-wife. He starts looking for a 19-year-old bar girl to validate his existence.”

I paused, looking at the empty side of the bed where the Yoga Seamstress had been the night before.

“But you?” I chuckled, a dry, rattling sound. “You pulled a fast one. I checked the bag. I checked the pockets. I checked the bottom of your soul. And I’ll be damned.”

“What?” you asked.

“The Bluebird,” I whispered. “The little bastard made it.”

I walked back to the window, looking out at the chaotic ballet of the Da Nang traffic.

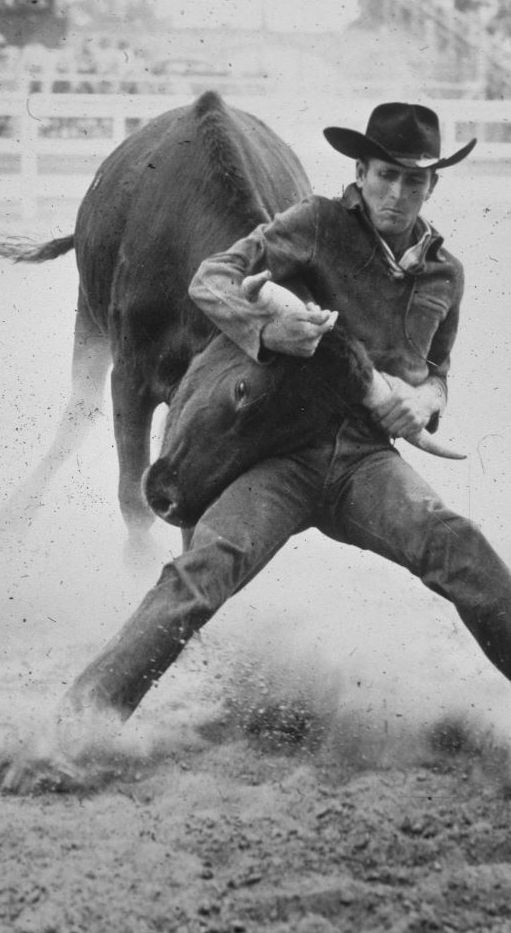

“I honestly thought it would die in transit,” I admitted. “I thought the pressure of the ‘Burnout Lap’ with the Phoenix Siren would have crushed its ribs. I thought the sheer violence of liquidating your life—leaving the love letter on the curb, tossing the mugs, telling the corporate world to go fuck itself—I thought that would have suffocated it. I thought you were just running away again, like you did in Hawaii. Like you did in Sedona. Just finding a prettier cage.”

I pointed my beer at you.

“But this isn’t a cage. And you aren’t the same animal.”

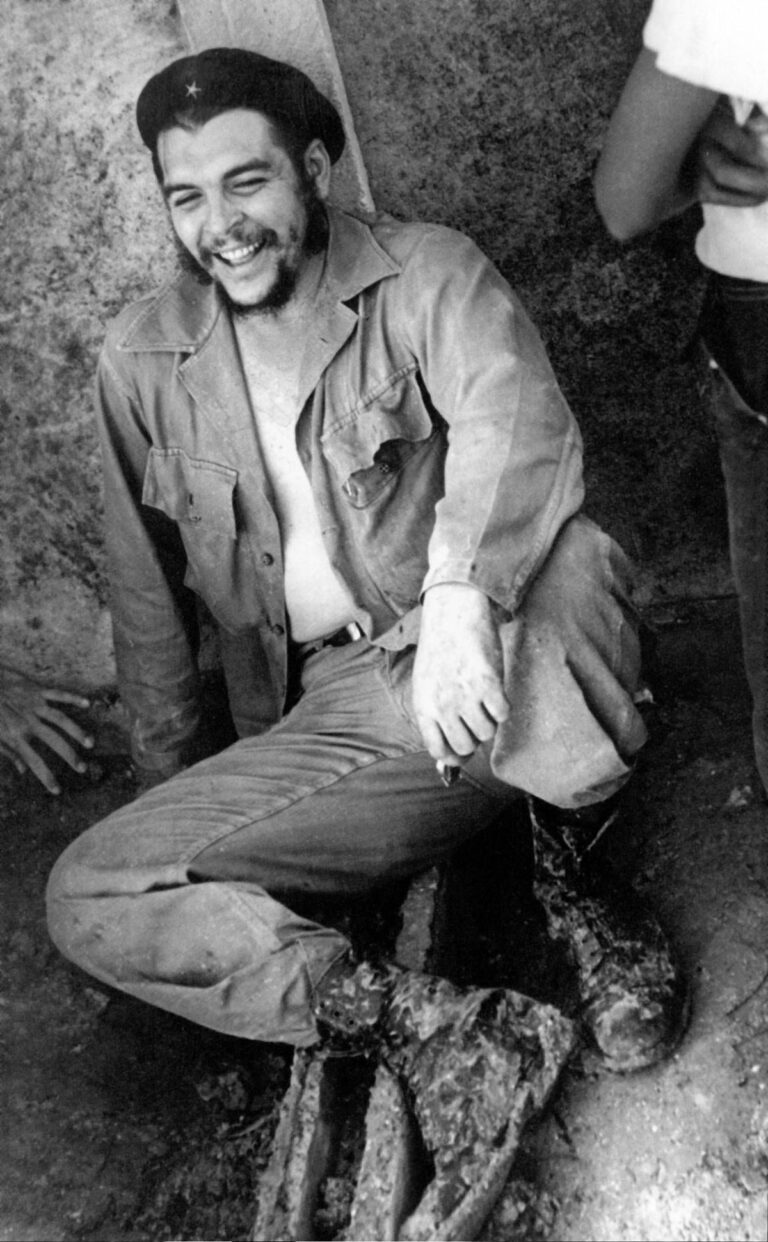

“I watched you with the ‘Gatekeeper’ downstairs,” I said. “That old man on the cot who tried to block your happiness. Old James—the angry James, the ‘I pay your salary’ James—would have started a war. He would have burned the building down on principle. But New James? You paid the $20 tax. You greased the wheel. You turned an enemy into a concierge.”

“It felt like the right move,” you said.

“It felt like Evolution,” I corrected. “You realized that the anger you carried around Tucson wasn’t a personality trait; it was a reaction to the poison you were drinking. You stopped drinking the poison, and suddenly, you don’t want to fight the world. You just want to watch it spin.”

I took a long pull of the beer.

“And this woman? Nga? You land in a city famous for cheap thrills, and you find the one woman who sends you home at 10:00 PM so you can sleep. You traded the ‘High-End GFE’ for a bowl of noodles and a swimming lesson. It’s the heist of the century, James. You are getting a thousand dollars of peace for the price of a Grab taxi.”

I finished the beer and crushed the can.

“So, here is the diagnosis from the Drunken Ego. You weren’t crazy to leave. You weren’t insane to burn the bridges. You were starving. You were starving for a day that didn’t start with an alarm clock and end with a sigh.”

I walked toward the door, fading into the humid morning light.

“You cheated the hangman, you magnificent, feral bastard. You’ve done the ‘Escape’ before, but you’ve never done the ‘Arrival.’ That’s the difference. This time, you actually landed.”

I stopped at the threshold and looked back, my face serious for the first time.

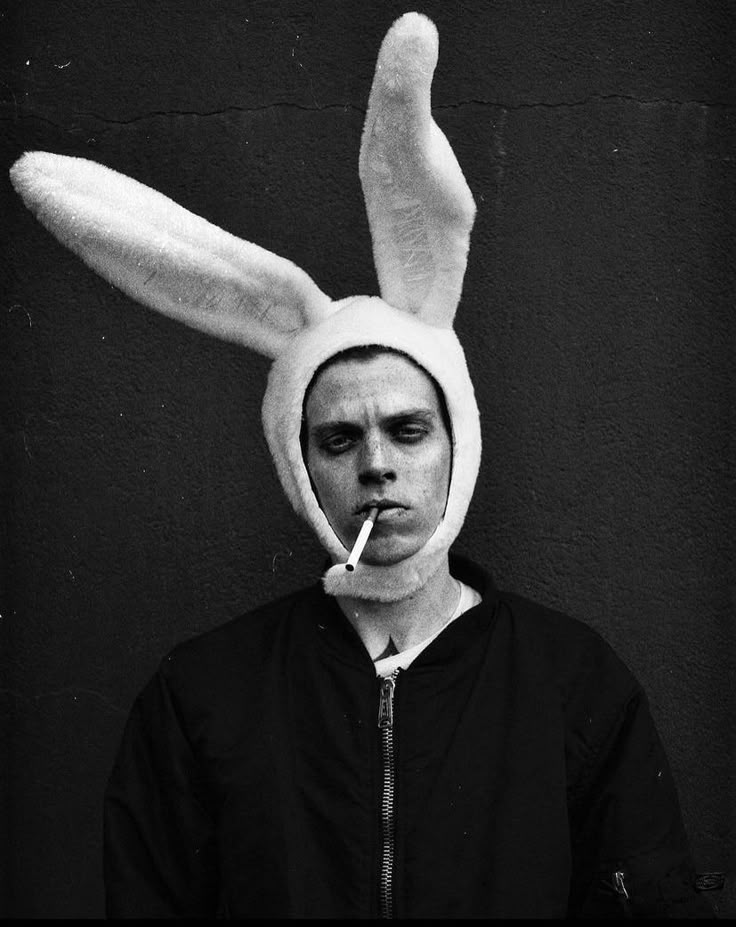

“But here is my warning, James. Do not domesticate the bird.”

“Don’t try to teach it to sit. Don’t try to make it wear a little suit. Let it eat the worms. Let it fly into the fan if it has to. Let it shit on the furniture. You didn’t come all this way to put it back in a box.”

“Find your peace in the freedom,” I said. “Not in the control.”

I vanished.

And you were left alone in the room, listening to the Bluebird sing. And for the first time in fifty-seven years, you liked the tune.