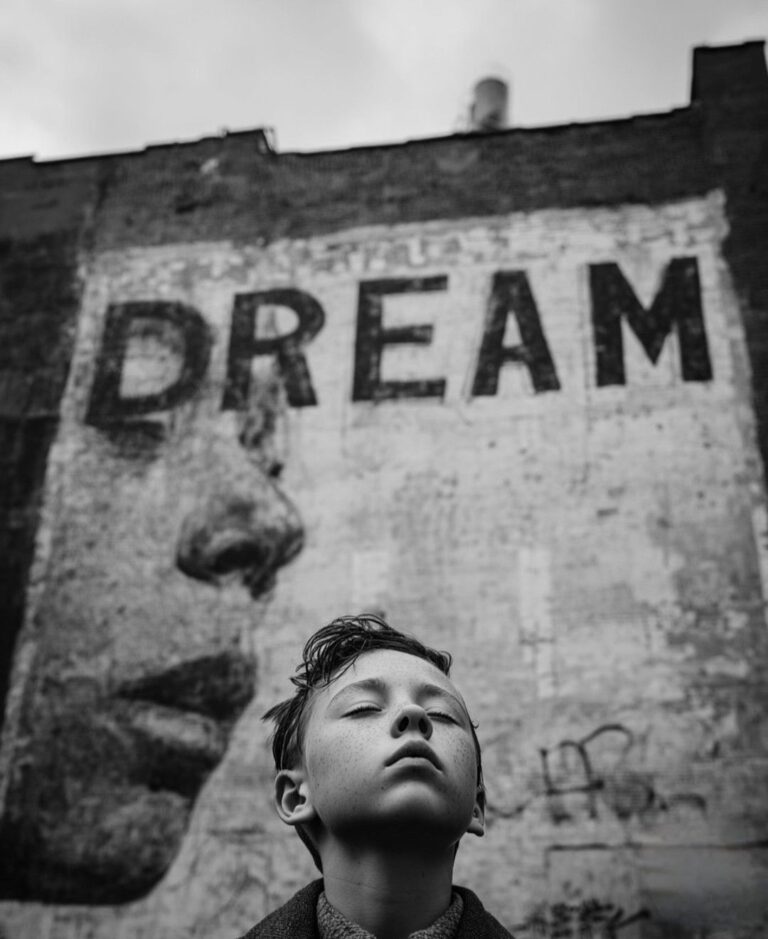

It’s 39 degrees outside. Pitch black. I’m sitting in a company truck, waiting for the heater to kick in, dreading the drive to a job I don’t want, for a company I don’t like.

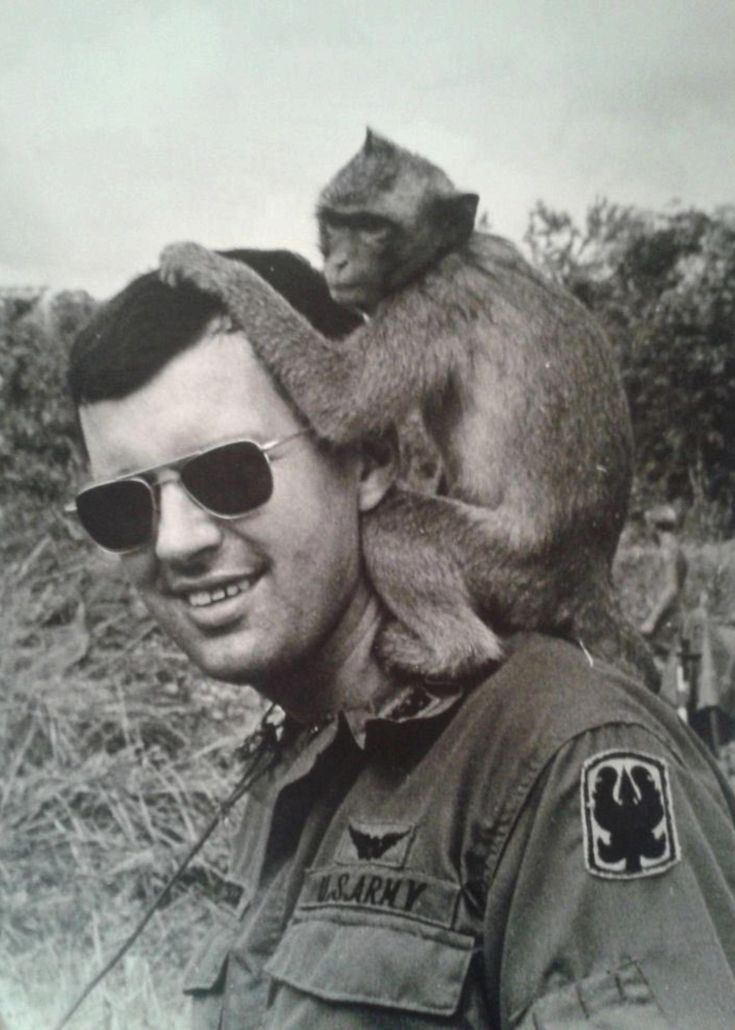

If I were where I’m supposed to be, it would be 7:00 PM. I’d be walking the beach in Da Nang, headphones on, watching the stars come out over the South China Sea. But I’m not there yet. I’m here, trapped in the final three weeks of a costume party that’s lasted fourteen years.

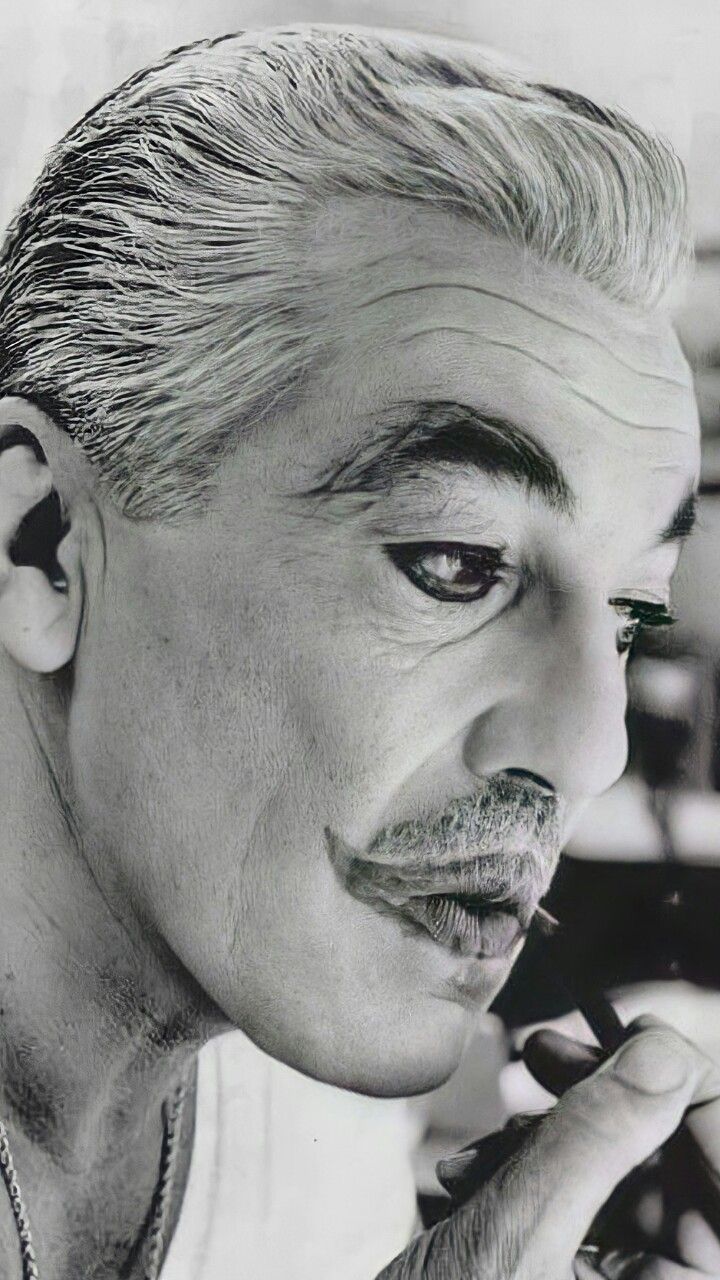

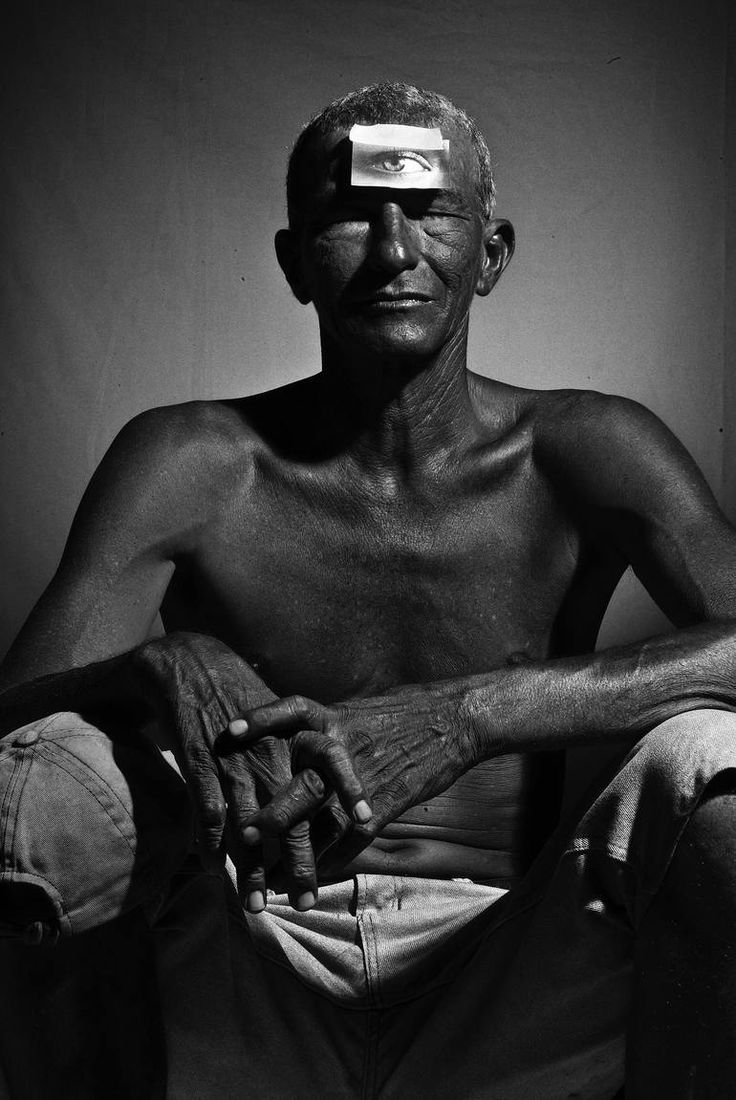

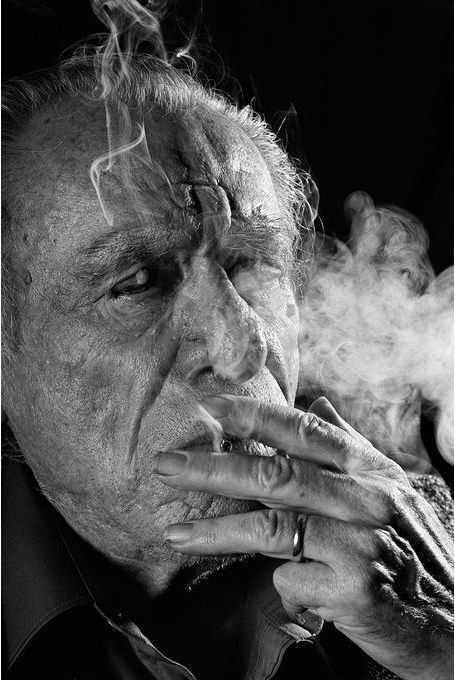

The costume is called “Senior Project Manager.” It fits because of the gray hairs and the beard. It fits because when I’m not joking around, I can stand in front of a room and look like the guy who knows where the bodies are buried. But it’s a lie.

I remember when the lie started. I was coming out of Sedona, broke, needing to feed the beast that was the State of Oregon’s child support division. I had a resume that screamed “unemployable”—not because I was incompetent, but because I was too dangerous. It listed President of Systematic Inc. It listed CEO of Northern Investments. I was a guy who owned the shipyards, not the guy who swept them.

I tried to go back to my roots once. I walked into an insulation company, thinking, I can do this. I like getting my hands dirty. The HR lady looked at my resume, looked at me, and actually laughed.

“You don’t belong here,” she said. “You’re overqualified. You’ll be bored in a week and gone in two.”

She was right. So I went home and did the hardest thing a man with an ego can do: I lobotomized my own history.

I had to “de-qualify” myself. I took a red marker to the CEO titles. I erased the real estate empires. I turned “Founder” into “Manager.” I murked up the waters so I looked like a good, obedient worker bee instead of a wolf. I dumbed it down so I could get a job that allowed the government to take my money.

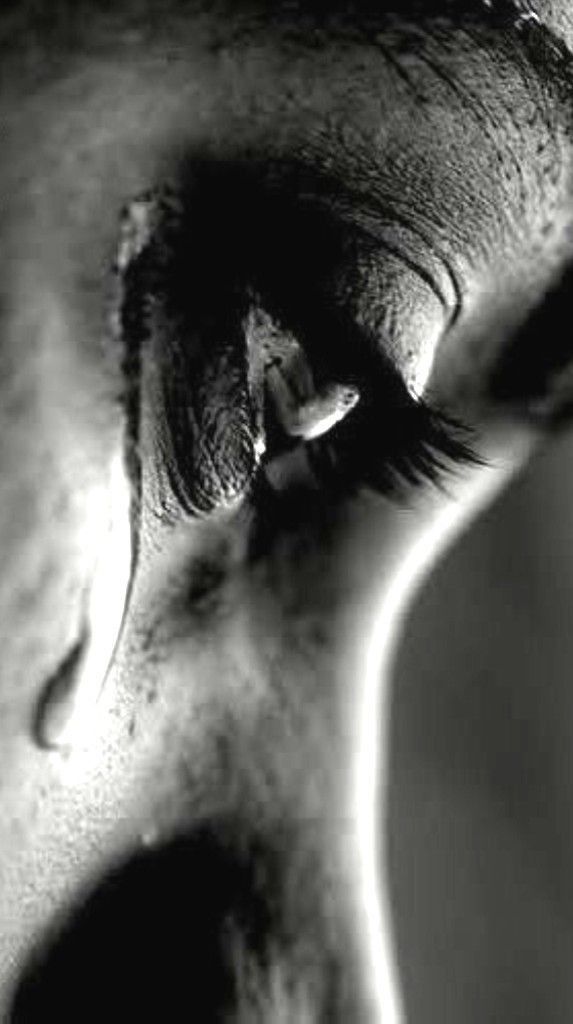

And in that process, somewhere between the edit and the paycheck, I lost myself.

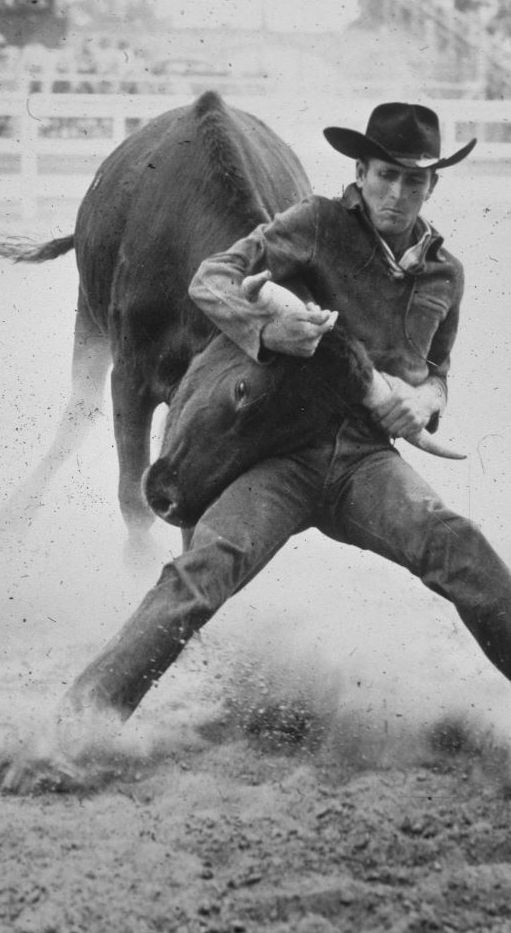

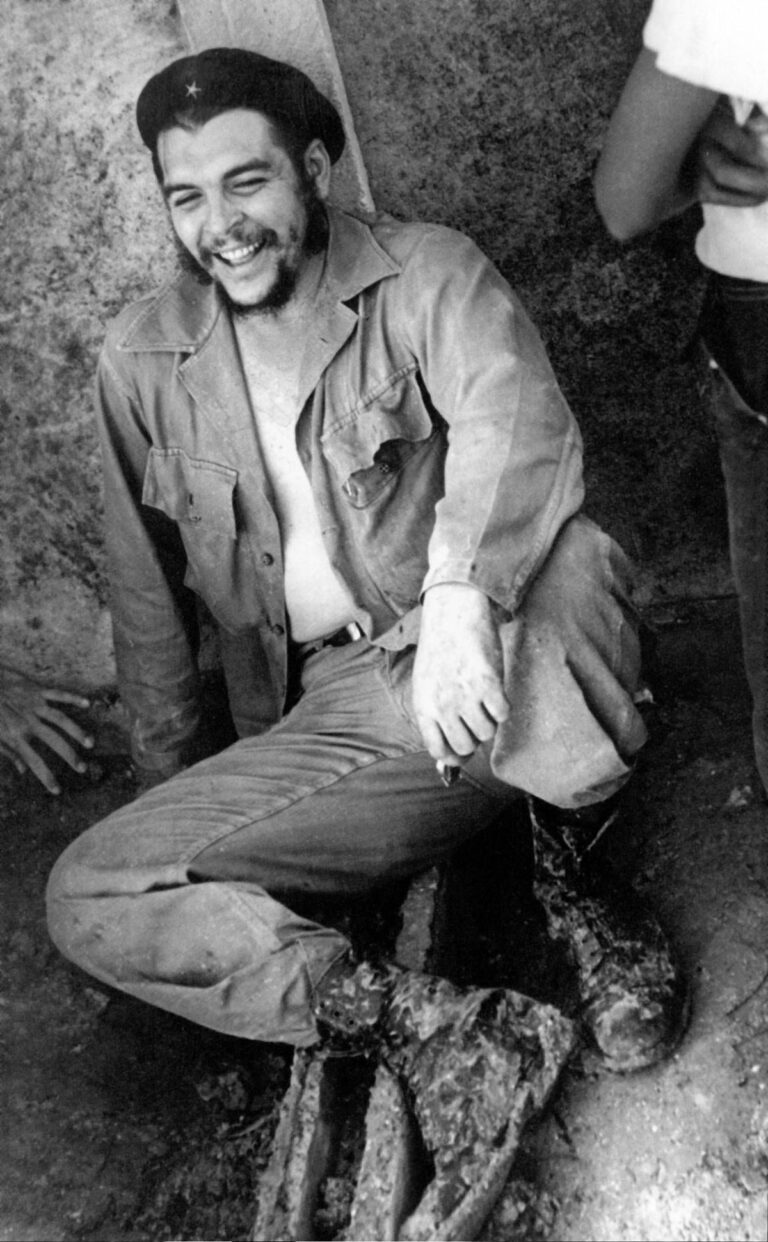

I ended up here, at the Walsh Group. They have systems for their systems. They want planners. They want guys who will nitpick a schedule for 18 months. That’s not me. Felix Construction ran a personality test on me once and they nailed it: “James is a Fixer.” I’m the guy you call when the building is on fire, not the guy you call to file the permit for the extinguisher. I’m a Maverick. But corporate construction doesn’t want Mavericks. They want compliant cogs.

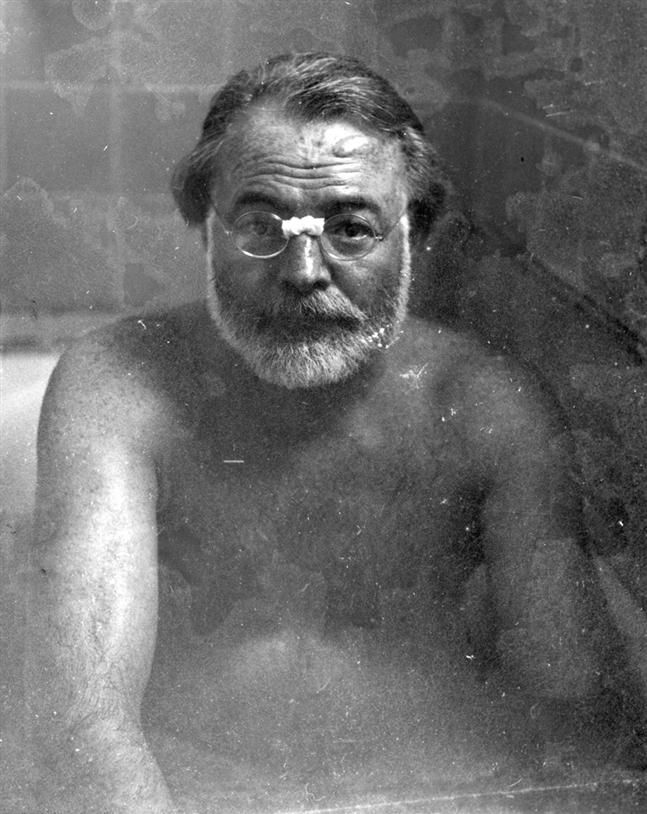

I realized how far I’d fallen today in the doctor’s office. He closed the door, looked at me, and asked about the plan.

“You’re just going to take off to Vietnam?” he asked. “You’re selling everything? That is… insane.”

He didn’t mean it in a bad way. He meant it with awe. It was the same look I used to get twenty years ago when I’d tell people, “I have no high school diploma, no college degree, and I’m a millionaire retired in Bend, Oregon.”

I used to have a shine to me when I told that story. I don’t tell it anymore. Now, I feel like an old, beat-up loser driving a truck in the cold. The shine is gone. The “Senior Project Manager” suit suffocated it.

But that’s why I’m leaving.

I’m not going to Vietnam to retire. I’m going there to perform an exorcism. I’m going to wake up when the sun is high, grab an iced coffee, and sit at a workstation that belongs to me. I’m going to learn AI. I’m going to build WordPress sites. I’m going to take a nap at 2:00 PM because I can. I’m going to execute a life that fits the Maverick, not the resume.

I have three weeks left of driving this truck in the dark. I have one contract left to drag out. And then, the costume comes off.

The “Fixer” is finally fixing his own life.