The address was 2442 Hill Street, Huntington Park. But to me, it was just the white house with the red trim. The fortress.

It sat there, solid and respectable, with a bird bath in the front yard that was a masterpiece of amateur masonry. When they poured the cement base, they’d stuck these exotic rocks into the wet mix—smooth, jagged, colorful stones that looked like jewels to a kid. It was decorative. It was tacky. It was perfect.

We had a stray cat named Tiger. My grandmother fed him, but she never claimed him. He was a mercenary. He lived for the bowl on the porch and the thrill of the kill. At night, you’d hear him yowling, a crazy, jagged scream as he fought off the other toms for territory. In the morning, the yard would be littered with piles of feathers, blowing in the wind like confetti. Evidence of a great hunt. Tiger liked it that way. No collar, no rules, just food and violence.

On the weekends, I was left to my own devices. And my device of choice was a belly crawler.

My uncle had cut the basket off a shopping cart, leaving just the bottom frame and the wheels. It was low, flat, and fast. I would lay on my belly on that metal grid for hours, patrolling the driveway like a shark in shallow water.

I always had a Band-Aid on my pointer finger. Always. A badge of honor from some forgotten scrape. And with that bandaged finger, I ruled the concrete.

My mission? Ants.

I would hunt them. Squash them. Or, if the sun was right, I’d get my uncle’s magnifying glass. I’d catch the beam, focus it into a tiny, blinding point of light on an unsuspecting worker ant, and watch. Pop. A tiny puff of smoke. A microscopic tragedy. I was a god with a lens, dispensing fire from the sky.

It was the quintessential Gen X childhood. You were alone. You were bored. You were dangerous.

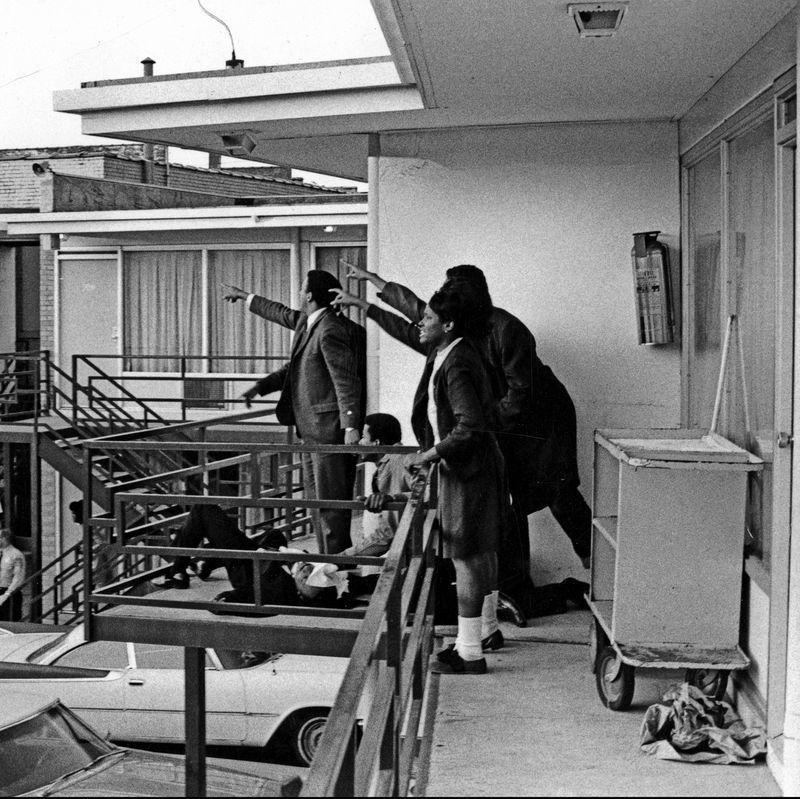

My grandfather, Johnny, would come out in his wife-beater, looking like a Mexican Marlon Brando. He’d lean on the fence and talk to the neighbor, an old Jewish guy with a cigar permanently grafted to his hand. The neighborhood was white then. “Life was white by all accounts.” My Uncle Brown, the gringo, owned the house. My grandparents were the first of the brown people, the vanguard of the change that would eventually sweep through the whole city. But back then? It was just two old men, smoke, and the quiet hum of the afternoon.

I don’t remember it ever raining. Not once. In my memory, Huntington Park exists in a perpetual, sun-bleached stillness.

The only water came from the garage.

My grandmother, Bertha, would hook the washing machine up to the utility sink. I’d watch the gray water drain out, a soapy river. And then, the magic. The Rollers. She’d feed the wet clothes into the wringer, one piece at a time. Squelch. The water would gush out, the fabric would flatten, and she’d catch it on the other side.

She’d take the basket to the clothesline in the backyard. Sheets, shirts, my grandfather’s undershirts, all flapping in the breeze.

And I would do the thing.

I would stand in the middle of the drying sheets. I’d close my eyes, tilt my head back, and just… inhale.

The smell of detergent. The smell of sun-baked cotton. The smell of ozone and clean air. It was intoxicating. It was the smell of a world that was ordered, clean, and safe.

I can still smell it. Standing there, hidden in the white maze of laundry, listening to the birds in the bath and the ants popping on the driveway, feeling completely, beautifully alone.

It was a kingdom. And for a little while, I was the king of Hill Street.