It was Brush Creek.

High up in the Sierras, where the air is thin

and the granite remembers everything.

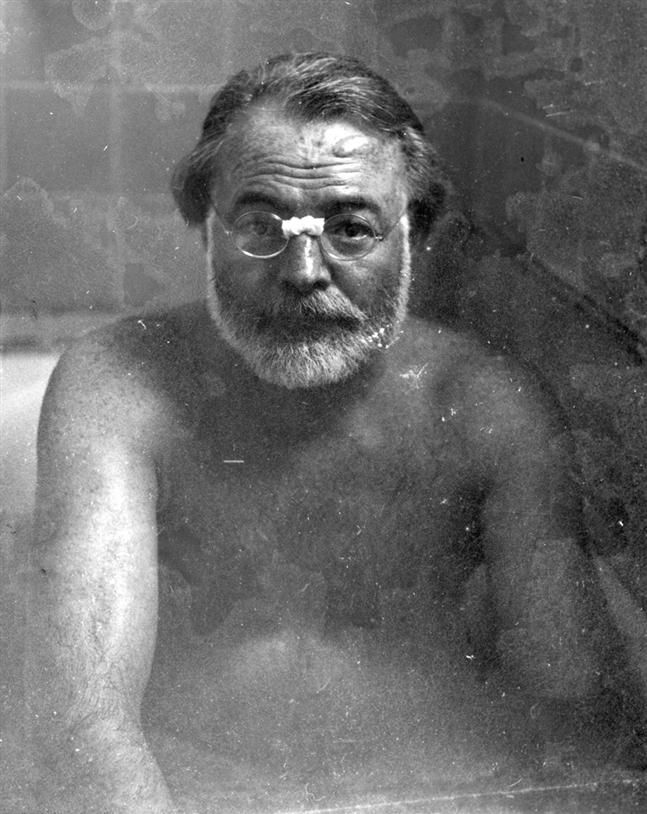

I was thirteen years old,

standing in water that was cold enough to numb the bone,

holding a fly pole like it was a foreign language

I was suddenly fluent in.

The trees looked familiar.

The rocks looked like old friends.

Ghosts of a toddler memory,

back when the organic father used to pack me up here

before the world split open.

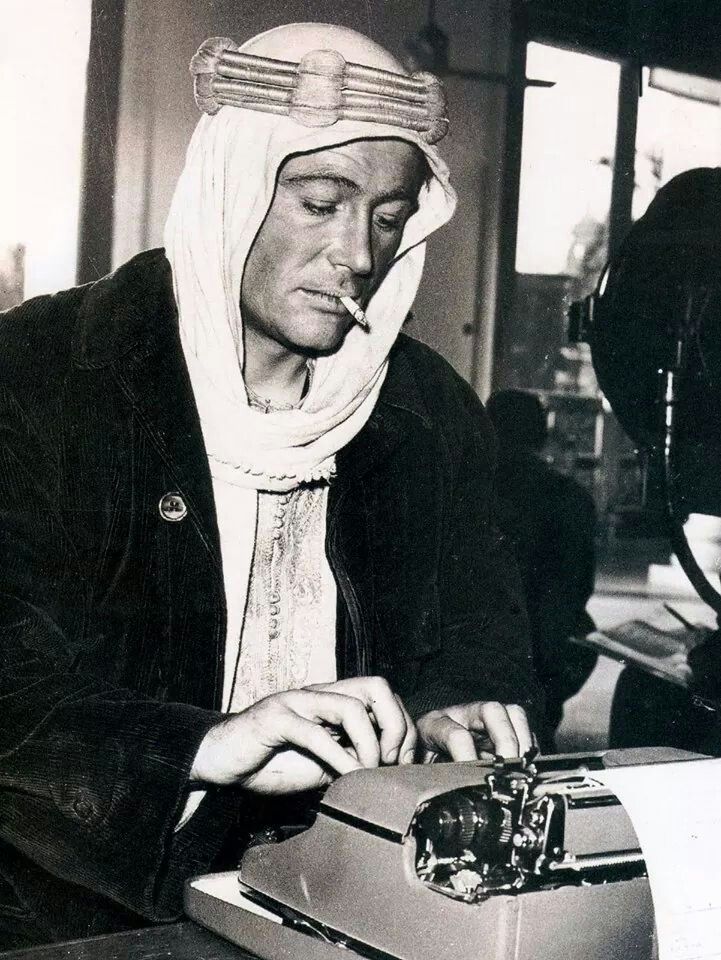

I cast the Royal Wolf.

I didn’t think about it. I didn’t calculate.

I just let the line go,

a perfect, lucky loop that dropped the fly

right into the throat of the pool.

And the water erupted.

A trout, hungry and stupid, took the bait.

The line went tight.

The rod bent.

I reeled him in, fighting the current, fighting the fish,

until I had him flashing silver in the net.

From the bank, he was watching.

The Artist. The man who knew the river better than he knew his son.

He was shouting, praising,

clapping his hands at the perfection of the kill.

“First cast! First fish of the day!”

But I just stood there.

I unhooked the fish. I looked at it.

I didn’t smile.

I didn’t jump.

I didn’t let out a whoop of joy.

Later, he asked me,

his voice confused, maybe a little hurt:

“Why didn’t you show any excitement?

That was your first fish.

Why the stone face?”

I couldn’t tell him then.

I couldn’t explain that the bluebird in my heart

was screaming with joy,

fluttering its wings against my ribs,

wanting to sing.

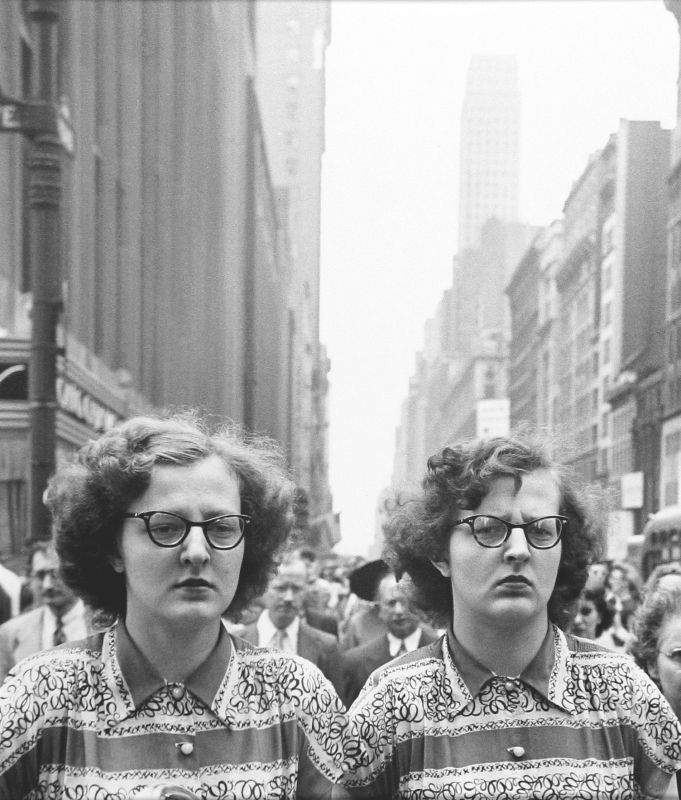

But I was thirteen.

And I had already learned the lesson of the feral years:

If you show them what you love, they can take it away.

If you show them you are happy, the hammer falls.

If you let the bluebird out,

the cat gets it.

So I kept him in there.

I poured the cold Sierra water on him.

I suffocated him with a tough-guy silence.

I acted like catching a miracle on a string

was just another job to do.

I acknowledged he was there,

deep inside,

celebrating in the dark.

But I wasn’t going to let him out.

Not for the fish.

Not for the father.

Not for anyone.

Because a man who doesn’t feel

is a man who can’t be broken.

Or so I thought.