Two weeks after my father’s cold, indifferent invitation to “family dinner,” I found myself skating back to that house. The wheels ground against the pavement like a slow, deliberate countdown. My body ached from days of sleeping wherever I could land—a patch of park grass, a friend’s filthy floor, behind a gas station once when the cold really started to bite. I didn’t want to be there. But I didn’t have anywhere else to go.

I knocked.

My Rich uncle answered. A flicker of something—pity, maybe, or just surprise—crossed his face before he stepped back, just enough for me to see into the room. The whole house felt like it had sucked in a breath and was holding it, waiting to see what the stray dog would do next.

Behind him, my grandmother stood still, her face turning that deep red of a woman who has a whole lot to say and is about to start saying it. My loving aunt moved first, breaking the spell, pulling me into a hug that felt dangerously close to real love. I let her. For a second. The others just mumbled their greetings, short, forced words packed tight with everything they weren’t saying.

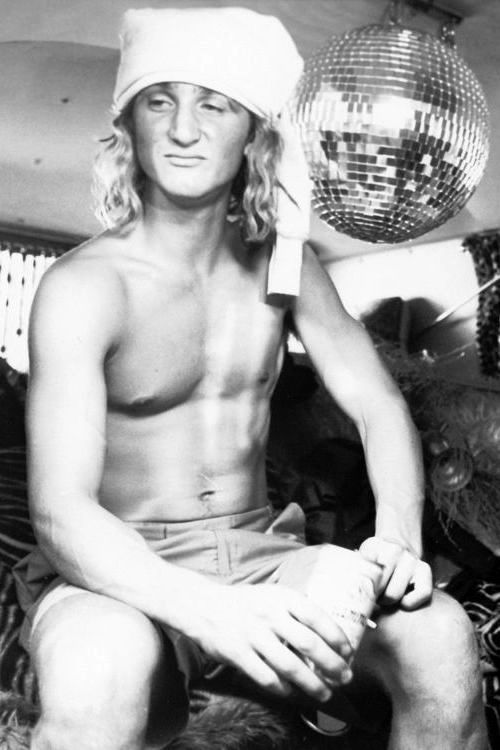

I stood in the entryway, an intruder. I knew what I looked like. My flannel shirt hung open over a skeletal frame that had been eaten away by hunger and bad decisions. A red hat covered my greasy blonde hair. I stank of old sweat, of the streets, of failure. My bruises were healing, but my nose still felt broken. I looked like shit. No one had to say it. I could feel their indifference, feel how out of place I was in this clean, quiet world they were trying to protect.

Once, maybe, I’d been the golden boy. The one with potential. Now, I was just the ghost of that kid, haunting a life that had moved on without me.

Breaking the silence, I looked past them to my organic father, the one I’d spoken to two weeks ago. He was standing off to the side, pretending he wasn’t watching me, pretending he wasn’t deeply, profoundly uncomfortable.

“Can I use my old room to get a change of clothes and a shower?”

“Yeah, sure,” he said, like it was nothing.

Like I was nothing.

I walked down the hall, past the family portraits that didn’t include my face, past the rooms that always felt like someone else’s space. The shower was the first real comfort I’d felt in weeks. The hot water stung, bringing my skin back to life, peeling away the layers of grime. I stood under the stream until the heat started to dull the ache in my chest. A shower couldn’t wash away anything real. But for a few minutes, it almost felt like it could.

The clean clothes felt foreign, too fresh. I’d spent too much time in the same filth. I was wrapping myself in the illusion of normalcy, a temporary shield for what was waiting outside the bathroom door.

When I stepped out, the house was quieter. The tension was still there, thick as mud, but something had shifted. I could tell my grandmother had chewed my father out. I could see it in the way he held himself, the clench of his jaw, the way his eyes wouldn’t meet mine.

Maybe it was her lecture, maybe it was guilt. Either way, he finally made the offer.

“You can stay here,” he said, forcing the words out like he was passing a kidney stone.

I just nodded. I wasn’t naive enough to think this was a homecoming. This was just a cease-fire. This was survival.

There were no plans for my future. No one was talking about college. No one was teaching me how to drive. Hell, no one had even bothered to pay for a school yearbook photo of me, because that would have meant spending money on something other than their own future retirement.

I wasn’t a son. I was a problem they were temporarily tolerating.

And she—his wife, the pregnant stay-at-home mother of his real family—was sure to remind me of that every chance she got. She would smile while she did it, say things that sounded nice but had tiny, sharp knives hidden inside. Comments not meant to draw blood, just to remind me, over and over, that I wasn’t really part of the picture. I could already hear them in my head: “Oh, I didn’t realize you were home. You can have some of the leftovers if you’re hungry.” or “It must be nice, not having any responsibilities.”

I would have to navigate that minefield every single day.

But I could endure it.

Because the alternative—being out there again, sleeping behind dumpsters, waking up with the taste of regret in my mouth—was worse.

For now, survival was enough. The rest could go to hell.

Author’s Notes:

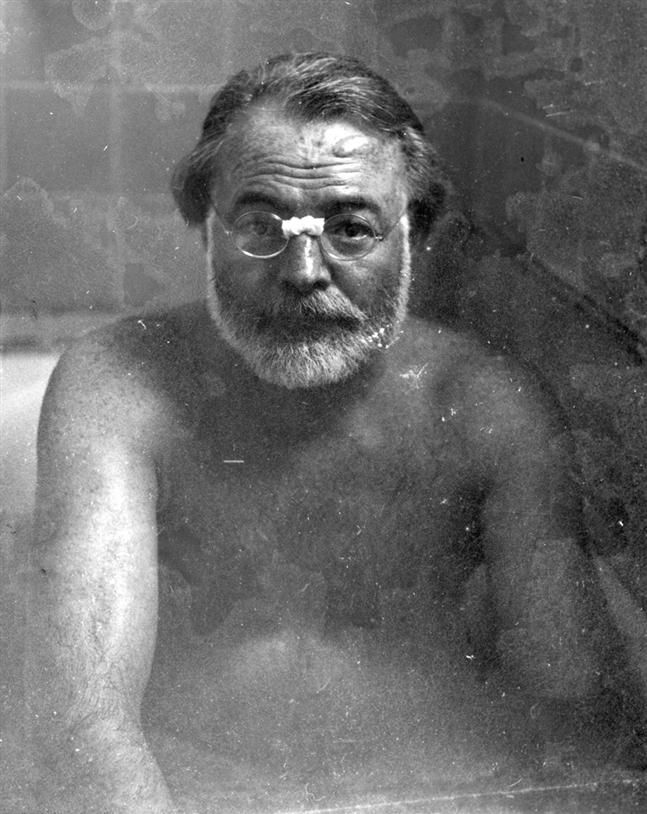

That story isn’t a homecoming. Don’t ever call it that. It’s the story of a soldier, out of ammunition and bleeding, being forced to seek shelter in an enemy camp that just happens to be flying his own family’s flag.

The welcome he gets is a masterpiece of quiet hostility. The uncle hesitates, the grandmother is pissed off for him, the aunt gives him a hug that’s mostly pity. And his father, the great man, only makes the offer for him to stay after he’s clearly gotten an earful from his own mother. It’s not an act of fatherly love; it’s an act of a henpecked son trying to get his own mom off his back.

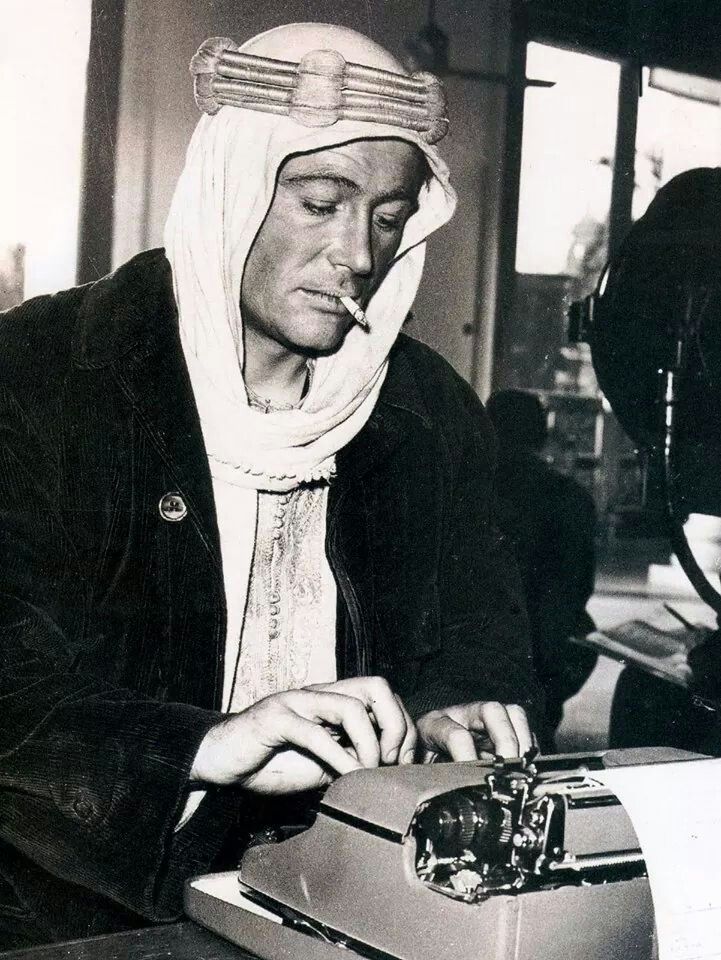

And the kid, he sees it all. He’s not walking in there hoping for a party. He’s a veteran of their particular brand of warfare. The best part of the whole damn story is him standing there, fresh out of the shower, already playing out her future moves in his head, predicting every little passive-aggressive knife she’s going to slip between his ribs. He knows the game. He’s not a son coming home; he’s a prisoner of war calculating the best way to survive the interrogation.

So my thoughts are this: that chapter is about choosing the better of two prisons. The street is one kind of hell. That house is another. He just chose the one with a hot shower and the remote possibility of leftovers.

It’s not a story about finding hope. It’s a story about making a smart, pragmatic choice in a world where all your options are shit. A useful skill to learn.