My Aunt Yoli and Uncle Vic, the gringo, they used to save me, in their own quiet, charitable way. They’d rescue me from the beautiful, ugly, and completely predictable chaos of my own house and take me on their trips to Yuma. I was a charity case, a quiet, little piece of baggage they’d throw in the back of the van with their own kids, a stray dog they’d feed for a weekend out of the goodness of their quiet, respectable hearts.

Uncle Vic, he was a good man, in his own quiet, conservative, and completely invisible way. A Maureen-looking sonofabitch who worked in a bottle factory, thirty years without a single missed day. A real rock. But his one, true, and beautiful piece of rebellion was that van. A bright yellow Chevy, a rolling monument to a decade that had better drugs and looser women. It had a goddamn painting of a naked broad on the side, a beautiful, airbrushed promise of a better, dirtier world. You’d open the door, and it was a time machine. Shag carpet, a little table that popped up out of the floor, couches that turned into beds. The whole damn thing smelled of stale beer, old pot smoke, and the quiet, desperate freedom of the open road.

They’d pick me up, and we’d head out, my cousins Yvette and Tina and me, a little tribe of lost children in a rolling cathouse. The little refrigerator was stocked with treats I’d never seen in my own house. These people knew how to live. They had the first microwave I’d ever seen. My aunt was a terrible cook—they lived on TV dinners—but that didn’t matter. The van was a goddamn spaceship, and we were on our way to another planet.

The trip itself was a long, slow, and beautiful piece of torture. You’d pass Palm Springs, then the Imperial Valley, and the world would just… open up. For a kid from the city, a kid who’d grown up in a world of two-story buildings and smog, to see the horizon, to see a sky that went on forever, it was a religious experience. You’d see real birds, not the scraggly, inbred little bastards that were one BB gun pellet away from extinction in my neighborhood.

And then you’d get to Yuma.

Christ. A real poop hole of a town. We’d stop at a Denny’s, and Uncle Vic would hold court, the hero of the hour, the man who had just driven his family through the desert. A quiet, beautiful, and completely bullshit performance from a man who was just happy to be out of the goddamn factory for a weekend.

After Yuma, you’d drive out to an Army station, and then you’d be on this long, empty military highway, just a ribbon of blacktop on a sea of brown, rolling desert. Up and down, up and down. My cousin Yvette, a delicate flower, she would always christen the side of the road with her breakfast. A beautiful, chunky, and completely predictable offering to the gods of motion sickness.

And then, after about thirty minutes of that, you’d see them. Little white trash trailers, bleached and beaten by the sun, scattered across the sand like a handful of discarded bones. And the first time I saw it, I remember thinking, My God, where the hell are we going? Is this where they take the bad children to die?

We parked in the back of one of those trailers, on the sand. The heat, it was a physical thing. An oven. Had to be a hundred and twelve, if not more. You’d get out of the van, stretch your legs, and the whole world was alive with things that looked like they could kill you. Lizards, snakes, spiders. A beautiful, ugly, and completely honest landscape.

An old man came out to meet us. He was in a little pickup truck, the bed full of bags of aluminum cans he was taking to California, where they paid a few cents more per pound. A real entrepreneur. He introduced himself as Uncle Vic’s dad. I called him Grandpa Lee from that moment on.

He fit the part. His skin looked like a piece of old leather that had been left out in the sun for a century. You couldn’t tell if it was the sun or if he was just three sheets to the deathbed. But he had a good spirit. And I could smell the alcohol on his breath, even though it was still mid-morning. A man after my own heart.

He led us around to the other side of the trailer.

And Christ. It was an oasis.

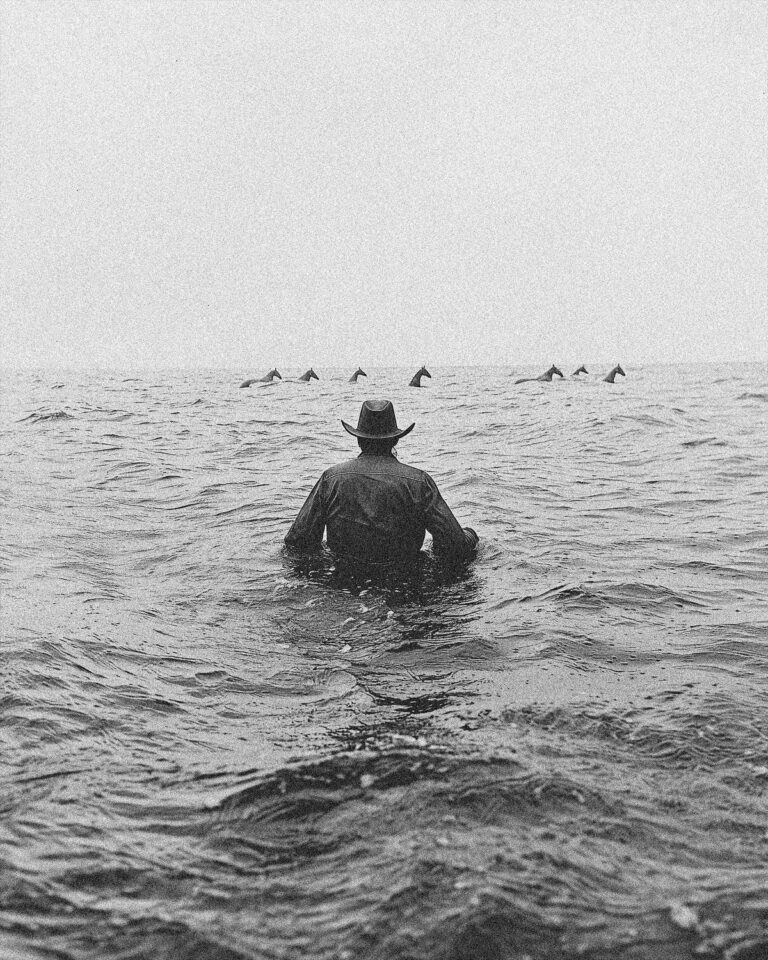

The back of the place was Death Valley, all sand and bones and the quiet, ugly hum of a world that was already dead. But the front? The front was paradise. Green grass, quail running around, brightly colored birds at a feeder, and a goddamn lake. Martinez Lake. A beautiful, ugly, and completely impossible slice of blue in the middle of all that brown. A million-dollar view from a ten-dollar trailer.

You’d walk inside, and the place was an ice cube, the A/C running full-blast. And there she was. Grandma Evelyn. She became my grandmother, too, from the first moment I met her until the day she died. She was a good woman. I recognized her from the old days, from the adult parties my parents used to have, the ones where the men and women would smoke cigarettes and drink hard liquor and tell dirty jokes, back before the Baby Boomers came along and ruined everything with their quiet, respectable, and completely soul-crushing good taste.

The inside of the trailer was a museum of a life that had been lived hard and well. Dark wood paneling, old pictures, a shotgun mounted on the wall. And a bar. A real goddamn bar, with a collection of bottles that would make a wino weep. They were drinkers. My people.

We’d spend the days on the lake. There was a long, ugly, and beautiful concrete path that led down a hundred yards to the boathouse. It was hot as a sonofabitch, but at the end of it was a little carpeted pier, and the cool, dark water. I spent the whole goddamn day in that water, a happy, stupid, and completely free little animal.

The next morning, Grandpa Lee, he woke me up. “Come on,” he said. He took me down to the little store in the neighborhood, and he bought a Styrofoam cup full of dirt and nightcrawlers. He took me down to the pier, and he showed me how to hook a worm, how to cast a line. He didn’t instruct me; he shared it with me. A quiet, beautiful, and completely honest transfer of wisdom from an old man to a young boy. We dropped a line in the water, and within three minutes, I had a bite. A bluegill. He showed me how to get the hook out, how to put the fish in a little underwater cage. Then he just left me there. And I sat on that pier all day, catching fish, in a state of quiet, peaceful, and completely beautiful solitude.

That night, they took us to the VFW hall. The place was full of people my grandparents’ age, all of them drinking Coors Lights and vodka, all of them happy, loud, and alive. They introduced me as their grandson, and I was in. They took me in, showed me how to play shuffleboard, asked me about my fishing. A beautiful, ugly, and completely honest tribe of old, happy drunks.

But it was the sunsets. And the stars. You don’t see colors like that in Los Angeles. You don’t see the goddamn stars. And the bats, they’d come out at dusk, a silent, beautiful, and completely terrifying ballet in the purple sky. That’s where I fell in love with the Southwest. And with the drinking.

I’d watch my grandparents. They’d start the morning with a screwdriver. A little beer in the afternoon. Wine and more beer at night. A perfect, beautiful, and completely functional haze of happiness that lasted all day long. There was no stigma then. They were happier than anyone I’d ever seen in Los Angeles.

And that’s the beautiful, ugly, and completely honest inheritance they left me. A love for the desert. A love for the drink. And a quiet, desperate, and beautiful memory of a place that doesn’t exist anymore.

Grandpa Lee died first, of course. Grandma Evelyn, she had to get a new heart. First a robotic one, you could actually hear it ticking in her chest, a zipper on her skin where they’d open her up. Then a pig’s heart. It worked, for a while.

But the family, it started to rot from the inside out. My Aunt Yoli, she got tired of the old woman, of her sickness, of her quiet, stubborn refusal to just die. And the property, it was on Army land, a lease. The military finally sold it off, and the rich people came in with their bulldozers and their architects, and they paved over paradise and put up a parking lot, or a golf course, or some other goddamn monument to their own quiet, respectable, and completely soulless version of the American dream.

But I still have the memory. A quiet, beautiful, and completely indestructible little piece of a world that was too good, too honest, and too goddamn real to last. A place where a man could be a man, a woman could be a woman, and a kid could just be a kid, fishing on a pier, with a head full of quiet, beautiful, and completely impossible dreams. A beautiful, ugly, and completely honest inheritance.